Gough Whitlam’s enduring legacies, from tariffs to universal healthcare

The lauded Labor PM left a bigger permanent legacy than many other leaders. Both sides of politics backed many of his big changes that, at the time, were controversial and polarising. And expensive.

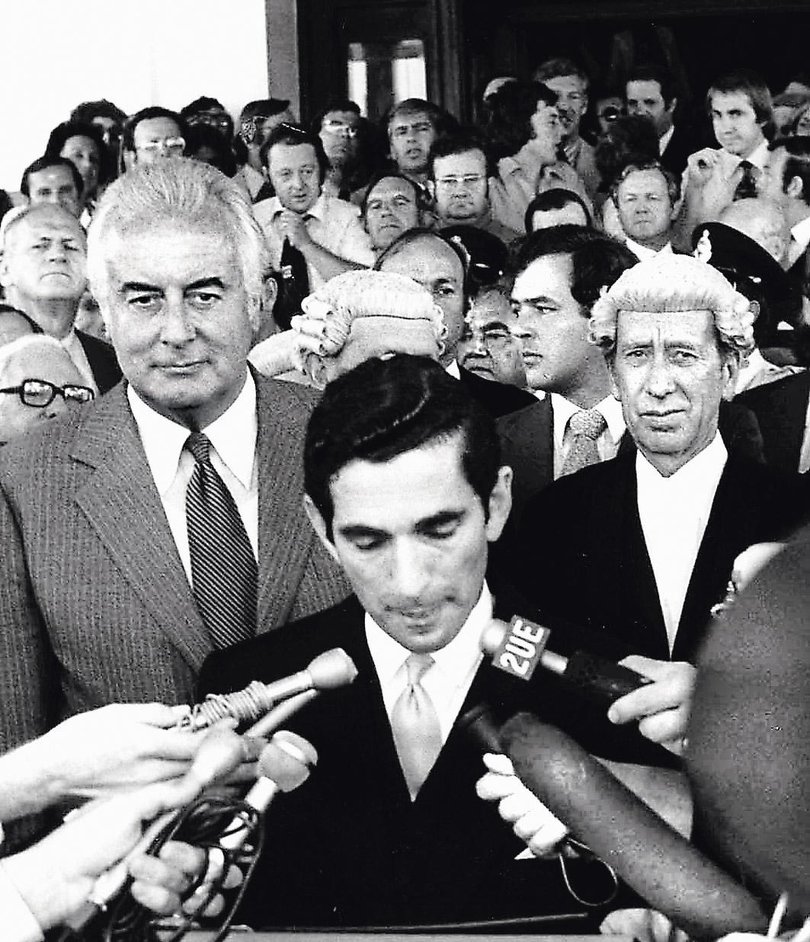

While he is most remembered for the way he was controversially removed from office 50 years ago today, Gough Whitlam remains Australia’s most transformative prime minister in terms of enduring economic and social policy legacies.

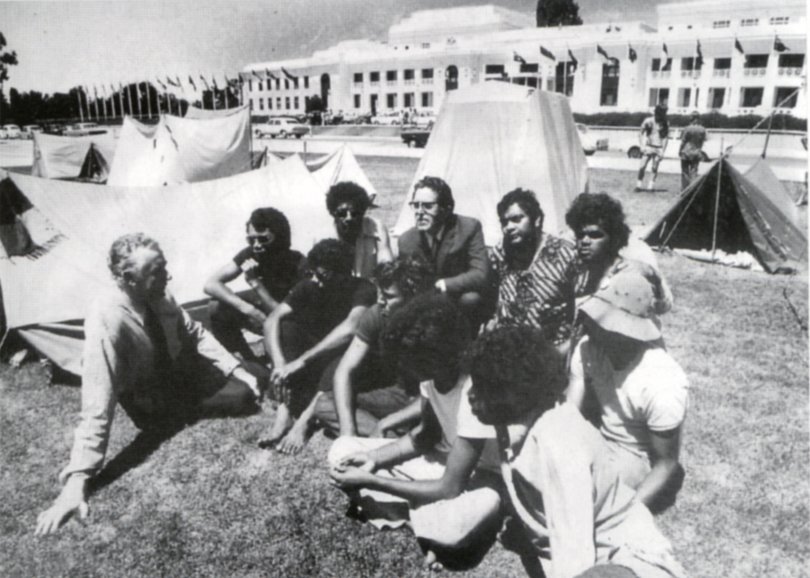

He was the PM who dismantled key aspects of the Australian Settlement, from the tariff wall to the White Australia policy, and introduced landmark changes from universal healthcare to Aboriginal land rights.

Plus, he established Australia Post and a government-run phone company Telecom, later to be privatised as Telstra.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.His three years in office, from December 1972 to November 1975, marked the biggest departure from the protectionist economic policies that had been around since Federation in 1901.

His big changes were controversial at the time. But his legacy is so profound and baked-in that neither side of politics would now dare undo it. His ideas have become very much part of the establishment.

Since his time in power, government spending as a proportion of the economy has never returned to the size it was in 1972, with the Commonwealth now required to solve more problems.

Whitlam, Labor’s first prime minister to have gone to university, also turned the ALP into a more middle-class party, with long-term consequences for Australia’s voting demographics.

The ALP became the party not just of teachers, but over coming decades, increasingly of the university-educated as fewer Australians left school early to work on factory floors manufacturing goods.

This led to a major political realignment in Australia, based on cultural values instead of just class.

The University of Sydney law graduate and barrister, who went to elite private schools in Sydney and Canberra, also turned Labor into the party more in favour of free markets.

Free trade

Both sides of Australian politics now accept the idea of minimal import tariffs or free trade so consumers can have cheaper goods.

But that certainly wasn’t the case during Federation in 1901 and the 72 years after that.

Australia’s first PM Edmund Barton had hailed from the Protectionist Party who, like Labor, were proponents of the tariff wall.

Since nationhood, high import taxes had been a key pillar of Australian economic policy, with the aim of protecting manufacturing jobs.

The conservative side of politics backed protectionism, despite having free traders and small ‘l’ liberals with free market ideals among their ranks. The old Country Party in particular had sway within the Coalition, with former farmer and deputy prime minister John “Black Jack” McEwen instrumental in bolstering the post-war tariff wall under long-serving Liberal prime minister Robert Menzies.

Australian-made Holdens and Fords dominated the roads during the 1950s and 1960s, with factories in Victoria and South Australia producing American and British-designed sedans, wagons and utes.

Australia went on to design and make its own models for the big open roads, from the homegrown Holden Kingswoods to our very own Ford Falcon.

The likes of the Australian Workers Union were particularly enthusiastic about tariffs.

Labor was just as protectionist so Australia could also continue being a country that produced televisions, washing machines and fridges.

But Whitlam’s Labor Government changed that in 1973, when the large and polarising Australian-designed Leyland P76 with a boot capable of holding a 44-gallon drum debuted at precisely the wrong time.

During Labor’s first year in office, Australian inflation had more than doubled to 12.5 per cent following the OPEC oil crisis that saw exports to the US banned in retaliation for it supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

In a bid to reduce inflation, the Whitlam government slashed tariffs by 25 per cent across the board, leading to import tariffs on cars falling from 45 per cent to 33.75 per cent.

The move was politically disastrous. Labor suffered a 14 per cent swing against it in the Bass by-election of June 1975, which was sparked by the parliamentary resignation of former deputy prime minister Lance Barnard, in order to allow him to become ambassador to Sweden, Norway and Finland.

Barnard, who had held the Launceston-based seat, quit politics because he felt he hadn’t been consulted about key decisions like the slashing of tariffs, Troy Bramston revealed in his new book Gough Whitlam: The Vista Of The New.

The byelection saw his old northern Tasmanian seat — which had been held by Labor since 1954 thanks to its union-aligned textile workers — switch to the Liberal Party’s Kevin Newman.

Just five months later, governor-general John Kerr dismissed Whitlam as prime minister and Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser was installed as the nation’s caretaker leader.

Under the new Coalition government, car tariffs soared to 57.5 per cent by 1978.

But since 1988, both sides of Australian politics have dismantled tariff barriers to the point they fell to just 5 per cent in 2010. Trade liberalisation, revived by Labor’s Bob Hawke, was also backed by Liberal PMs from John Howard to Tony Abbott.

The 2000s and 2010s saw free trade deals signed with the likes of Japan, Thailand, South Korea and China that took import tariffs to zero, eliminating a key pillar of the Australian Settlement that Gough had begun dismantling.

By 2017, Australia no longer had a local car industry, when Holden made its last Commodore in Adelaide.

White Australia abolished

Whitlam was also the prime minister who officially took the White Australia policy off the statute books, even though it was the previous Coalition governments that had dumped the racist dictation test in 1958 and allowed non-white migrants into Australia, leading to an influx of Asian students during the 1960s.

But the 1973 scrapping of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, initially designed to stop indentured labour, also saw the doctrine of assimilation replaced by multiculturalism, under colourful immigration minister Al Grassby, who was believed to have had Calabrian Mafia connections in the NSW Riverina.

Communications policy

The splitting of the Postmaster-General’s Department into Australia Post and Telecom, a government-run telephone company, wasn’t finalised until December 22 — just nine days after the 1975 election that resulted in the Coalition winning under caretaker PM Malcolm Fraser with a massive 55-seat majority.

But towns and suburbs across Australia still have an Australia Post thanks to a process stared under Whitlam.

And the establishment of Telecom, initially as a local calls phone company run by the government, led to Telstra being formed in July 1995 as a merger with OTC, the old Overseas Telecommunications Commission.

Telstra was eventually privatised between 1997 and 2006.

Economic legacy

During the final months in office, the Whitlam Government under social services minister Bill Hayden established Medibank, a form of universal healthcare.

While it was abolished under the Fraser government, its revival as Medicare under the Hawke government meant the Liberal and National parties could only ever win elections if they promised to keep it intact.

Fraser’s passage of the Aboriginal Lands Rights Act of 1976, started under Labor, demonstrated a bipartisan commitment to enabling Indigenous people to make land claims based on traditional custodianship, leading to the 1992 Mabo High Court decision and native title legislation in 1993.

Whitlam’s three years in office lasted about as long as the much-ridiculed Leyland P76.

But in that time, he took apart key elements of the Australian Settlement, a term coined by journalist Paul Kelly to describe an inward-looking Australia in his book The End of Certainty.

Whitlam turned Australia into a more open economy and a society that would eventually become much more multiracial, and more reliant on the state.

Government spending as a proportion of GDP soared from 18.5 per cent when Whitlam took power in 1972 to consistently remain above 21.7 per cent.

Governments are now required to solve more social problems to the point that under Anthony Albanese, government spending made up 26.2 per cent of GDP during the last financial year.

That was higher than the 24.3 per cent level of 1975-76 covering the Dismissal and Fraser’s first six months in office.

Bigger government, free trade, universal healthcare and multiculturalism have endured 50 years on from that fateful day, leaving Whitlam with a bigger permanent legacy than any other prime minister since Federation. Making him part of the establishment he so railed against.