Whitlam adviser: King Charles participated in palace plot to dismiss Labor government in 1975

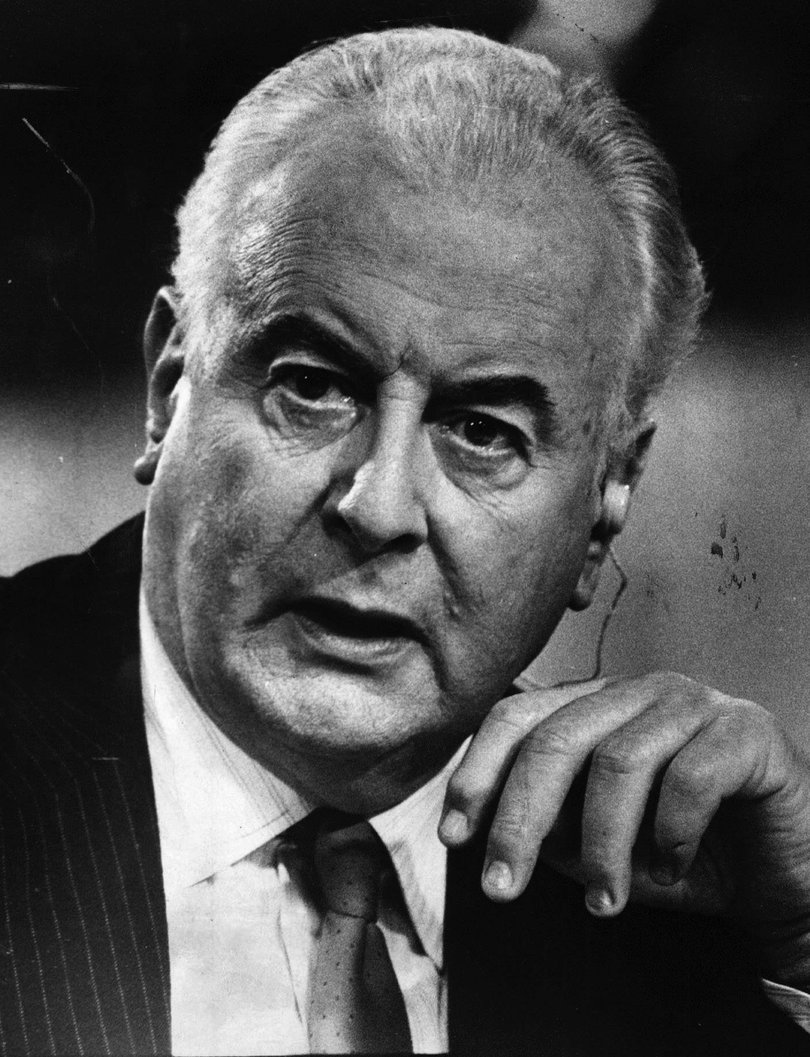

The comments by the head of Gough Whitlam’s department, John Menadue, show how the Labor Party continues to see itself as the victim of an establishment conspiracy.

Fifty years ago an event took place so shocking that the reverberations continue to shake politics today.

On November 11, 1975, Gough Whitlam’s reformist government was removed from power by the Queen’s representative, an act seen as so unfair, treacherous and undemocratic that feelings of victimhood and injustice persist within the Labor movement half a century later.

The head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet under Whitlam, John Menadue, insists King Charles was, as a 26-year-old prince, part of a palace plot to remove the left-wing government from power.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“Charles was a very active participant in the dismissal of Gough Whitlam 50 years ago,” Mr Menadue wrote on his personal blog Friday.

“Don’t make any mistake about that. Charles was up to his royal ears in it. He was not politically neutral. He sided with privilege and aristocracy.”

Arrogance and contempt

Today, a new biography of the Labor legend — written by a man from the left — frames the dismissal differently. Historian, political columnist and former Labor adviser Troy Bramston argues one of the Whitlam Government’s core failures was its leader’s arrogance and contempt towards colleagues.

The new perspective not only challenges Labor’s self image as a victim, it may explain why Anthony Albanese has been so unexpectedly successful.

The Labor Party’s conventional view is the Whitlam Government was destroyed by establishment forces threatened by its progressive social and economic policies. They included a much bigger role for government in the economy, an expansion of the welfare state and support for arts and culture that defied the ruling order.

“My disgust at the breach of constitutional conventions involved, and my fear that it could all happen again if we were not very careful indeed, remains largely undiminished,” former Labor attorney-general and foreign minister Gareth Evans wrote in The Australian today.

The conspiracy theory became so popular it was used in a Hollywood film. In The Falcon and Snowman a CIA employee defects to the USSR after discovering the CIA is orchestrating the sacking of Whitlam by Governor-General John Kerr.

Whitlam appointed Kerr, a NSW judge, who has been an arch villain in Labor lore since — a working-class success who ascended to vice-regal office and turned class traitor.

A different perspective

What if the primary cause of Whitlam’s downfall was himself? What if Whitlam held the worst attributes of an establishment politician and none of the finest?

The son of a government lawyer, Whitlam was an academic success at the elite Canberra Grammar School and Sydney University’s law school. Convinced of his intellectual superiority, he was a terrific orator and terrible colleague. “He was shy, a loner, had few friends and rarely confided in anyone,” Bramston writes.

His principal private secretary, John Mant, told Bramston the prime minister’s arrogance made the office a difficult place to work, which helps explain why the government seemed so disorganised. “There was no sense of team because Gough’s view was that everyone was largely useless, and they were largely pissants,” he said.

Whitlam’s uninterest in the advice was fatal. Bramston reveals Whitlam was repeatedly told by senior public servants the governor-general could sack him to resolve a budget crisis. The Senate had refused to pass the budget, which meant the government was in danger of running out of money.

Whitlam, who died in 2014, did not believe Kerr was bold enough to take such a drastic step and expected the finely balanced Senate to break under political pressure.

Senior party and government figures were not so sanguine. They worried Kerr would use his powers as head of state — long assumed to be ceremonial — against the government. Among them was Bill Hayden, Frank Crean, Gordon Scholes, Fred Daly and David Combe, according to Bramston. Whitlam ignored them.

Mr Scholes, the speaker, was one of the first Labor MPs to learn the government had been sacked. “Contingency plans for a complete departure from accepted parliamentary practice and the accepted role of the governor-general had not been prepared,” he wrote afterwards.

A persistent legacy

Today, the Whitlam Government is celebrated today for its social policies, including introducing no-fault divorce, universal healthcare, advancing Indigenous land rights and ending the death penalty. Whitlam’s contribution to the arts was epitomised by the purchase of Jackson Pollack’s Blue Poles painting, a decision so momentous it was chronicled in a book this year by the Guardian’s political editor, Tom McIlroy.

Among ardent Labor supporters, the Whitlam era receives greater adulation than Albanese’s. But as the Financial Review’s political editor, Phillip Coorey, argued today, Anthony Albanese’s political success seems to have been born in Whitlam’s failure.

As the Albanese Government implements left-wing policies across swaths of government, including the arts, industrial relations, housing, welfare, health, education, industry and foreign affairs, they are met not with establishment hostility but acquiescence.

To explain Mr Albanese’s political effectiveness, Coorey recounted a speech given by the then leader of the opposition in 2019, six months after he took the job.

At the time, the predominant view towards the ex-university activist and factional organiser was scepticism, especially on left. His refusal to issue new policies made it feel like the Labor Party was drifting. Speaking with a strange intonation that even strangled the word “Australia”, he was powerfully uninspiring. Entirely un-Whitlam-like.

In the speech, Mr Albanese argued patience was necessary. The election would be won on election day, he said, not months or years before.

He ignored the criticism, won an election promising little change and increased his majority the second time round. All while implementing policies that would have thrilled Whitlam’s cabinet, including siding with the Palestinians in a war they started against Israel.

At the heart of Mr Albanese’s success as a political leader is his inoffensiveness. He is not rude, arrogant or condescending. He treats colleagues respectfully. They repay the favour by not undermining him.

Whether you admire or detest the prime minister, he deserves credit for learning from Labor’s mistakes. Perhaps the Coalition should too?

As for the allegation the palace was involved in a plot against Whitlam, letters from the time, made public five years ago, show the Queen and Prince Charles were aware Mr Kerr was considering removing the government. But they did not try to influence his decision.