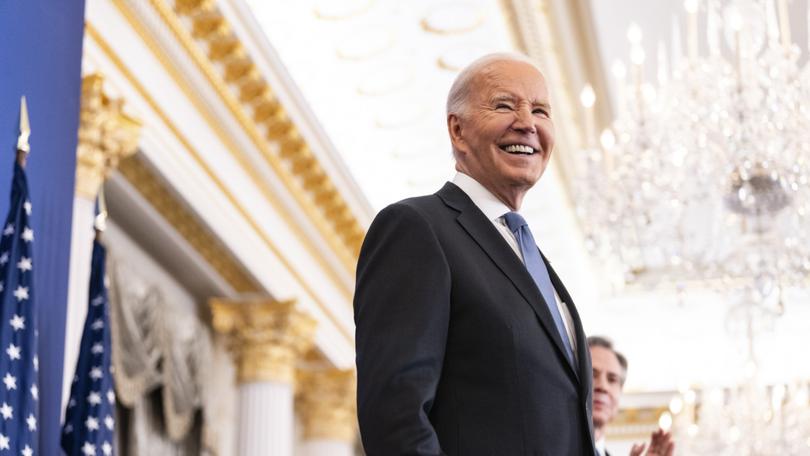

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Biden promotes his foreign policy during his final week in office

President Joe Biden kicked off his final week in office with a robust defence of his foreign policy, arguing in a speech that America had grown stronger on his watch and had ‘the wind at our back’.

WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden kicked off his final week in office with a robust defense of his foreign policy, arguing in a speech that America had grown stronger on his watch and had “the wind at our back.”

With just seven days left until President-elect Donald Trump takes over the White House, Biden hopes to use his remaining time to frame his historical legacy as a transformational leader who bolstered the United States domestically and internationally in just a single four-year term.

The effort got underway with a speech at the State Department focused on what Biden sees as his successes in the international arena. He said that he strengthened U.S. alliances in Europe while facing Russian aggression, as well as in the Asian-Pacific amid the rise of China. At the same time, he argued that America’s adversaries — particularly Russia, China and Iran — were all weaker than when he came to office.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

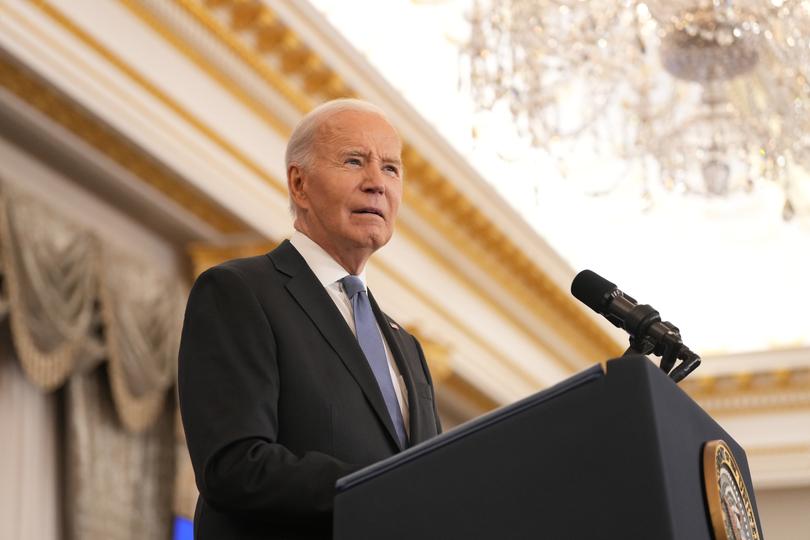

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“Right now, in my view, thanks to our administration, the United States is winning the worldwide competition,” Biden said. “Compared to four years ago, America is stronger, our alliances are stronger, our adversaries and competitors are weaker. And we have not gone to war to make these things happen.”

Biden was hosted in the department’s eighth-floor auditorium by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, his longtime adviser, and welcomed with a sustained and even emotional standing ovation by political appointees and lawmakers. Foreign policy has long been a passion of Biden’s, and he wanted to devote a full address to it before leaving office.

He argued that he had improved the United States’ position in the world by making it stronger at home, enhancing the “sources of national power” by expanding the economy, investing in the semiconductor industry and rebuilding roads, bridges, airports, clean water systems and other public works.

He boasted of eliminating the leader of al-Qaida, even though he withdrew U.S. troops from Afghanistan; ending the war there; imposing new restraints on China while rallying its neighbors; and working to combat climate change. And while the wars in Ukraine and the Gaza Strip still rage, he claimed credit for helping Ukraine and Israel defend themselves against different kinds of threats even as he talked about trying to bring peace to the Middle East.

“Make no mistake, there’s serious challenges the United States must continue to deal with,” Biden said, ticking off a number of them. “But even so, it’s clear my administration is leaving the next administration with a very strong hand to play. And we’re leaving them an America with more friends and stronger alliances, whose adversaries are weaker and under pressure, an America that once again is leading.”

Biden never mentioned Trump by name nor addressed how radically different his successor’s worldview is or what might happen in the next four years. But there were a few pointed lines.

He said that it was “more effective to deal with China alongside of partners than going it alone,” a seeming allusion to Trump’s “America First” approach. Biden also said the world should “make sure Putin’s war ends in a just and lasting peace for Ukraine,” a nod to Trump’s desire to broker a deal with President Vladimir Putin of Russia.

He also implicitly contrasted his influence among European allies with that of Trump, who bullied NATO partners to increase their military spending. While just nine NATO allies were meeting a target of spending 2% of their economies on their militaries when Trump left office, Biden said, 23 now meet that goal.

The speech was the first this week aimed at presenting the best case for Biden’s presidential legacy. He will deliver a broader televised farewell address to the nation in prime time Wednesday evening, much as other presidents have done. He will also deliver at least three other speeches this week: on his conservation record, at a farewell ceremony for the commander in chief and before the nation’s mayors.

On foreign policy, Biden has presided over a tumultuous time, and Trump blamed him for the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, although no U.S. troops are directly involved on the ground in either place. Some critics said the perception of a world aflame and spinning out of Biden’s control contributed to the erosion of his political popularity at home and ultimately his withdrawal from the presidential race under pressure.

“The fact that Biden is handing the presidency back to his predecessor is in part a reflection of his foreign policy shortcomings,” said Peter Rough, the director of the Center on Europe and Eurasia at the Hudson Institute and a former aide to President George W. Bush.

“For most of his time in office, Biden has been on the defensive, first in Ukraine and then in Gaza,” Rough continued. “The president’s 1990s-era liberal internationalism may have been well intentioned, but it always felt out of step to me with the power politics of the 2020s.”

Still, a Gallup poll released Monday showed that America’s standing in Europe had improved strikingly under Biden. Of 30 NATO allies surveyed, approval of U.S. leadership rose among all but four since 2020, Trump’s last year in office. Approval ratings rose by double digits in 20 of the 30 countries. In Germany, for instance, approval of U.S. leadership rose to 52% under Biden from just 6% under Trump.

By most assessments, Biden revitalised NATO after relations with Washington frayed under Trump, who came close to pulling the United States out of the alliance and regularly harangued European partners. Biden welcomed two new members, Sweden and Finland, and led the delivery of tens of billions of dollars in arms and other aid to Ukraine.

In his speech Monday, Biden taunted Putin, boasting that Moscow had failed to achieve the strategic goals of its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to take over its neighbour and drive a wedge between the United States and its allies.

“When Putin invaded Ukraine, he thought he’d conquer Kyiv in a matter of days,” Biden said. “The truth is, since that war began, I’m the only one that stood in the middle of Kyiv — not him. Putin never has.”

Biden has been criticised on Ukraine from two different directions: Some said he was too reluctant to deliver more powerful weapons to Ukraine for fear of escalation with a nuclear superpower, while others said he invested too much American treasure in someone else’s war.

Biden argued that he had turned around the rivalry with China, both by forging new partnerships in the Asian-Pacific region and by bolstering old ones while also strengthening the U.S. economy to better compete.

He noted that experts once expected China’s economy to surpass America’s. “Now, according to the latest predictions, on China’s current course, they will never surpass us,” he said. “Period.”

The president offered no regrets in his speech, not even for the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. In extricating America from the longest war in its history, Biden finally accomplished what his two predecessors wanted to but could not. But the chaotic nature of the withdrawal did considerable damage to both his and the country’s standing in the world.

Biden said he grieved for the 13 U.S. troops killed by a suicide bombing during the withdrawal but did not acknowledge the Afghan allies who were left behind or the fact that the withdrawal opened a vacuum for the Taliban to take over the country again. “Ending the war was the right thing to do, and I believe history will reflect that,” he said.

The war in Gaza that followed the Hamas terrorist attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, was the other dominating crisis of Biden’s tenure. He stood staunchly by Israel and provided weapons for its all-out assault on Hamas, but eventually grew frustrated with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, who rebuffed U.S. pressure to do more to curb civilian casualties and relieve humanitarian suffering.

As with Ukraine, Biden faced criticism from opposite directions. Some accused him of not doing more to stop the killing of civilians and called him “Genocide Joe” at protests. Others, conversely, faulted him for putting any pressure at all on Israel to restrain itself in the face of a profound terrorist threat.

Biden argued that the past year had devastated Israel’s enemy, Iran, which has sponsored not only Hamas but also Hezbollah, as well as the Houthis and other regional militias. He also took credit for twice deploying U.S. forces to successfully defend Israel from Iranian missile attacks. “Iran is weaker than it’s been in decades,” Biden said.

Some critics, however, contend that Iran is weaker not because of Biden but because Israel ignored Biden’s advice to hold back and instead demolished Hamas, Hezbollah and Iran’s own air defense systems.

But even now, in his final days in office, Biden is straining to seal an elusive ceasefire agreement that would end the fighting and result in the release of Israeli hostages held in Gaza, including a few with U.S. citizenship.

Biden spoke with Netanyahu on Sunday and with Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, the emir of Qatar, who is among the brokers of ceasefire negotiations, on Monday. He also planned to call President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi of Egypt. “We’re pressing hard to close this,” he said.

Biden offered no advice to Trump on how to solve conflicts in the Middle East or other issues around the world. The only advice he explicitly gave was urging “the next administration” to focus on artificial intelligence and the transition to clean energy.

He noted that some around Trump deny climate change. “I think they come from a different century,” he said. “They’re wrong. They are dead wrong. It’s the single greatest existential threat to humanity.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times