THE NEW YORK TIMES: Inside the battle for America’s most consequential battleground state

There may be seven main battlegrounds in the race for the White House, which could prove crucial. But one state stands apart as the place that strategists have circled as the likeliest to tip the election.

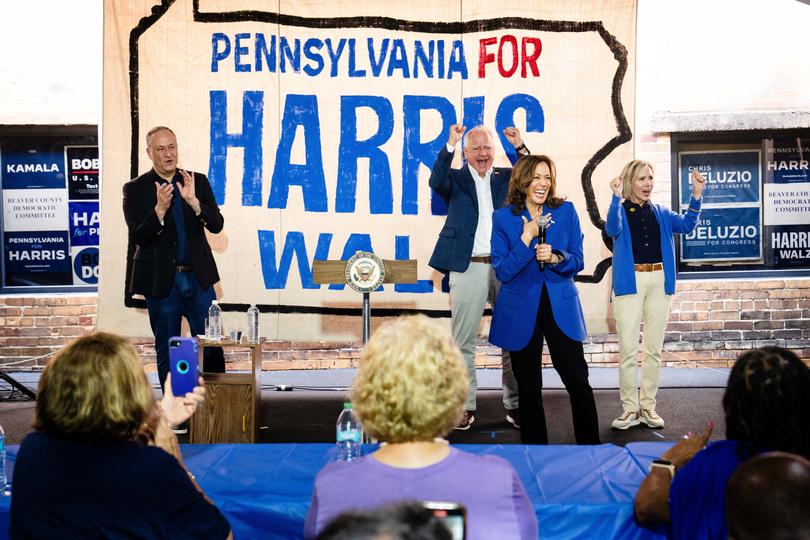

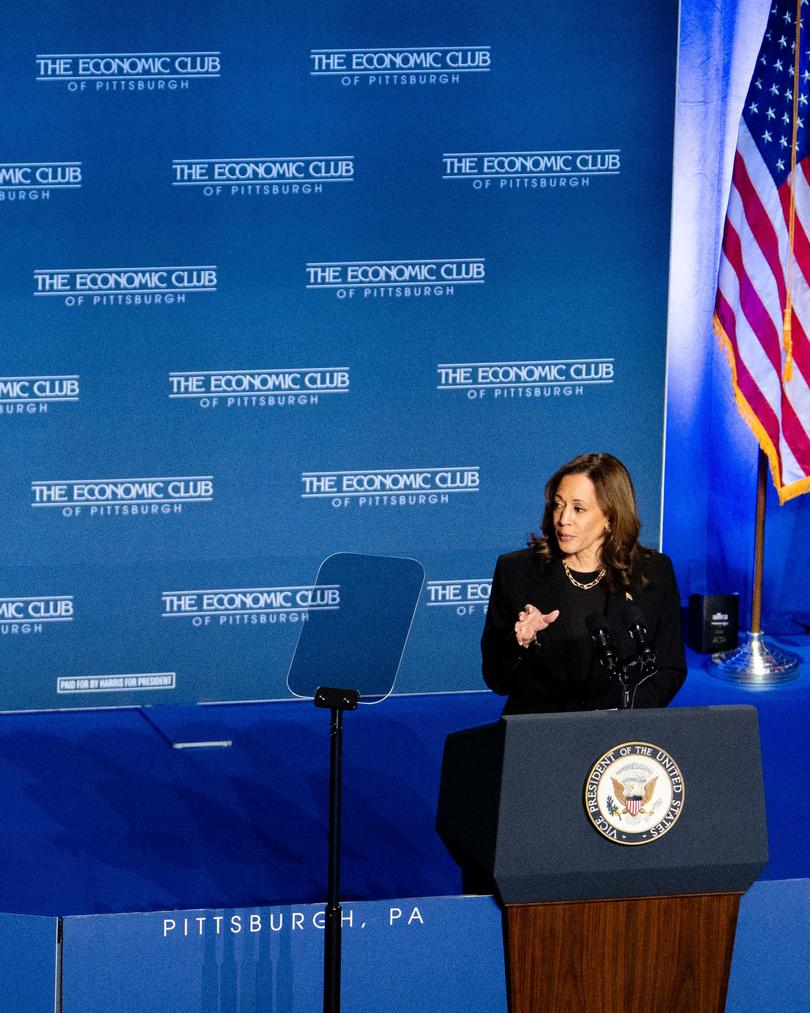

When Vice President Kamala Harris rolled out her economic agenda, she went to Pittsburgh. When she unveiled her running mate, she went to Philadelphia. And when she had to pick a place for former President Barack Obama’s first fall rally this Thursday, it was back to Pittsburgh.

Former President Donald Trump has earmarked the greatest share of his advertising budget for Pennsylvania and has held more rallies in the state than in any other battleground since Harris joined the race — including two Wednesday and three in the last week.

Welcome to the United States of Pennsylvania.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.There may be seven main battlegrounds in the race for the White House in 2024, all of which could prove crucial. But Pennsylvania stands apart as the state that top strategists for Harris and Trump have circled as the likeliest to tip the election.

Both candidates are pouring more money, time and energy into the state than anywhere else, with Harris, Trump and their allies set to spend $350 million just on television ads in Pennsylvania — $142 million more than the next closest state and more than Michigan and Wisconsin combined.

Part of Pennsylvania’s pivotal role is its sheer size: The state’s 19 electoral votes are the biggest prize of any battleground. Part of it is polling: The state has been virtually tied for months. And part of it is math: It is daunting for either Trump or, especially, Harris to reach the 270 Electoral College votes needed to win without it.

“If we win Pennsylvania,” Trump said at a recent rally in the state, “we win the whole thing.”

A ‘Microcosm of America’

What makes Pennsylvania so compelling — and confounding — for both parties is the state’s unusual mix of demographic and geographic forces.

It is home to urban centers such as Philadelphia with a large population of Black voters whom Democrats must mobilize. It has fast-growing, highly educated and mostly white suburbs where Republicans have been bleeding support in the Trump years. There are struggling industrial towns where Trump needs to maximize his vote, and smaller cities booming with Latino immigrants where Harris aims to make gains. And there is a significant, albeit shrinking, rural population. White voters without college degrees, who make up Trump’s base, still account for roughly half the vote.

“This is almost a microcosm of America,” said Austin Davis, Pennsylvania’s Democratic lieutenant governor.

The campaigning in Pennsylvania is fierce and everywhere — the intensity of a mayoral street fight playing out statewide, with consequences for the whole country. Harris is running online ads targeting voters in heavily Hispanic pockets of eastern Pennsylvania and radio ads featuring Republicans voting for her on 130 rural radio stations. Her team said they knocked on 100,000 doors in the state Saturday, the first time the campaign had reached that threshold in a day.

Trump has dispatched his running mate, Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, to make more stops in the state than in any other, according to a campaign official, and the state is also where Trump held his lone town hall with Sean Hannity on Fox News.

On Wednesday, Trump returned for a rally in Scranton, with another one, in Reading, on his schedule that night, his eighth and ninth in the state just since Harris entered the race. In Reading, a majority-Hispanic city, Trump has been offering free haircuts at his offices there on Sundays during Hispanic Heritage Month, according to the campaign.

And while the former first lady Melania Trump has yet to campaign anywhere, Harris’ husband, Doug Emhoff, knocked back a beer while watching a football game recently in a Philadelphia suburb and spoke at a large get-out-the-vote concert Friday featuring singer Jason Isbell in Pittsburgh.

The campaigns are even trying to keep key Pennsylvania activists and officials happy. It was no accident that at both the Republican and Democratic conventions, only delegates from the nominee’s home states had better seats than Pennsylvania’s.

“It’s the centre of the universe,” said Cliff Maloney, who is leading a multimillion-dollar effort called the Pennsylvania Chase to get more Republicans to vote by mail in the state.

Davis said the last time he saw Harris, he joked that she should rent an apartment in the state. She laughed. But in September, Harris was in Pennsylvania 1 out of every 3 days — a remarkable share for a single battleground.

Gov. Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, was not selected as Harris’ running mate, but he has made numerous appearances for her, including at her rally in Wilkes-Barre, at a bus tour kickoff in Philadelphia and at another event with writer Shonda Rhimes in a suburb of Philadelphia.

Harris now has more than 400 staff members on payroll in the state spread across 50 offices, according to her campaign. The Trump campaign declined to comment on its Pennsylvania staff but said it had more than two dozen offices in the state.

On a recent Saturday, Harris’ Pittsburgh headquarters was abuzz with volunteers grabbing packets of literature to canvass local neighbourhoods. One mother and daughter had driven through Hurricane Helene’s remnants from Illinois to volunteer. “I want to put my rubber on the road where it really matters,” Beth Hendrix, 53, said of the decision to trek to Pennsylvania.

On the wall behind them was a poster of the 65,000-seat Pittsburgh Steelers football stadium. It serves as both a door-knocking goal and a stark reminder that the excruciatingly small difference between winning and losing the state in 2016 was even less than the number of seats in the stadium.

Only 44,292 votes.

Bullishness on Both Sides

At times, the national race has looked shockingly local.

Harris has picked up spices at Penzeys in Pittsburgh (she purchased a creamy peppercorn dressing base, among other items), stopped by a local bookstore in Johnstown and grabbed Doritos at a Sheetz gas station in Moon Township.

Trump has swung through a Sprankle’s Market in Kittanning (he bought popcorn and gave one shopper $100) and stopped for cheesesteaks at Tony and Nick’s in Philadelphia.

Just how evenly divided is Pennsylvania today? It is the only state in the nation where Democrats control one chamber of the state Legislature and Republicans the other. And the margin in the state’s lower chamber is a single seat. The state is also home to one of the nation’s most costly Senate races and two competitive House seats that could tip control of Congress.

Democrats are bullish that the party has won key races for governor and the Senate in recent years, including in 2022. But Republicans are optimistic because voter registration has swung sharply toward the GOP.

The day Trump won Pennsylvania in 2016 there were roughly 916,000 more Democrats than Republicans in the state. As of Monday, that figure had dwindled to 325,485.

Earlier this year, one of the most competitive suburban counties ringing Philadelphia, Bucks County, tipped to the Republican column by voter registration. And in September, Luzerne County, just outside Scranton, became the latest to turn red by registration. Trump won the county in 2016 by 19 percentage points, only four years after Obama carried it narrowly.

One X factor is the regional impact of the assassination attempt on Trump in Butler County. Some local supporters predicted in interviews that it would inspire the pro-Trump area to turn out in droves. Trump held a large rally there Saturday with guests that included the world’s richest man, Elon Musk.

Abraham Reynolds, 23, who runs a cleaning business in North East, Pennsylvania, was at the Butler rally when Trump was shot. “That really encouraged me to go out and take action,” said Reynolds, who became a campaign volunteer and is now a Trump captain.

Precision Targeting

No demographic stone is being left unturned by either side.

In their debate, Harris dug deep into the state’s demographic ledger as she laced into Trump’s desire to walk away from the war in Ukraine. “Why don’t you tell the 800,000 Polish Americans right here in Pennsylvania how quickly you would give up?” she scolded him.

Trump has plotted his own appeals to that population, including a late September trip to attend Mass at a Polish Catholic shrine in Bucks County on the same day as the Polish president, Andrzej Duda. The trip had to be scrapped over security concerns.

The two campaigns have also used policy as a wedge.

Trump has tried to use Harris’ opposition to fracking during her 2020 primary run to weaken her support, especially in western Pennsylvania, which is home to some of the world’s largest deposits of underground natural gas. Harris has since reversed that position.

Kenneth Broadbent, the business manager of Steamfitters Local 449 in Pittsburgh, said his union had endorsed Harris but that his membership remained divided. Though Harris gave a shout-out to the jobs created by a local battery plant in her Pittsburgh economic speech, Broadbent said his members wanted to hear more about jobs.

“She needs to come out with an energy policy,” he urged.

Trump has even dangled some specific policy proposals for the state, sometimes clumsily. As president, he signed the law that eliminated deductions for state and local taxes from federal returns. As a candidate, he has promised to reverse that law.

“For all the suburban households paying high property taxes here in Pennsylvania,” he said at a recent rally in Indiana County, “I will restore the SALT deduction.” The tax break applies chiefly to high earners, and Trump was speaking in a working-class community.

Few people applauded.

“You guys don’t know what the hell it is,” Trump said of the tax break. “That’s a good one.”

Some of the most precision targeting has occurred online. Pennsylvania is the first state to top $50 million in ad spending this year on Google.

Trump’s campaign spent more than $80,000 to show one longer video on Google’s platforms, just in Philadelphia, about Harris’ shortcomings for the local Black community.

Harris, meanwhile, has been running online ads in majority Hispanic cities like Reading and using a narrator with a Caribbean accent to better appeal to Puerto Rican and Dominican populations there, according to her campaign.

“It’s a margins game,” said Dan Kanninen, Harris’ battleground states director.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times