THE NEW YORK TIMES: The US election polls are close. The results might not be

KALEIGH ROGERS: These two things are true: The US election polls show Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump effectively tied. And, close polls do not necessarily mean a close result.

These two things are true about the presidential race: The polls show Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump effectively tied. And close polls do not necessarily mean there will be a close result.

This may feel counterintuitive, but the fact is that we are just a very normal polling error away from either candidate landing a decisive victory, especially in the Electoral College.

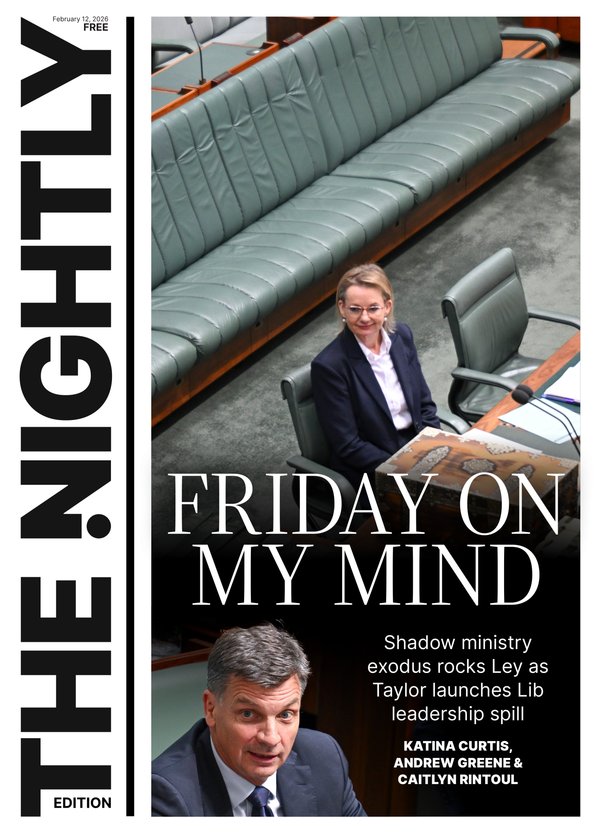

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.This is a point my New York Times colleague Nate Cohn has made regularly in his election race updates over the past few weeks. But it bears repeating, because a lopsided result when there is an expectation of only razor-thin margins could further fan distrust in the polls and in the electoral process itself.

“You can have a close election in the popular vote and somebody could break 315 Electoral College votes, which will not look close,” said Lee Miringoff, director of the Marist College Institute for Public Opinion. “Or you could get a popular vote that is 5 points” apart, he added, “which is, by today’s standards, a landslide — a word no one has used this year.”

Since 1998, election polls in presidential, House, Senate and governor’s races have diverged from the final vote tally by an average of 6 percentage points, according to an analysis from FiveThirtyEight. But in the 2022 midterm elections, that average error was 4.8 points, making it the most accurate polling cycle in the past quarter-century. If polls were off this year, in either direction, by the same margin, the winning candidate would score a decisive victory.

Based on where the polling averages stood Monday if the polls are underestimating Harris by 4.8 points in each of the seven swing states, she would win every one of them, and a total of 319 electoral votes, compared with only 219 for Trump. If those same polls underestimate Trump by the same margin, he would win all the battleground states, for a total of 312 electoral votes. (These calculations assume Harris and Trump each win the other states they are favoured in.)

The polls may not all miss in the same direction, or by that magnitude. But even a historically accurate year for the polls could mean either candidate sweeps most of the battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Preelection polls have a certain amount of error baked in, partly through the polling process itself, but largely because they have to guess who is actually going to turn up to vote, in order to match the sample they have to that voting population. Other public opinion polls that focus on nonpolitical topics don’t have to deal with that challenge.

“Because the tools pollsters have to forecast turnout are fairly limited — stated intention to vote, interest in the election, perceived importance of the outcome, past turnout — they may all make the same mistakes if those tools don’t turn out to be that useful in a given election,” said Scott Keeter, a senior survey adviser at Pew Research Center.

Who shows up to vote obviously makes a big difference in terms of who wins. The biggest lead in any swing state right now is Trump’s in Arizona, where polling averages show him ahead by 3 points, so even a miss as small as 2 or 3 percentage points could mean a big victory for either candidate.

Part of this is because polls tend to miss in the same direction in a given election cycle (though not always), and battleground states that are demographically similar tend to vote the same way (though, again, not always). As a result, if the polls are off by even a small margin, but off in the same “direction” (either underestimating Trump or underestimating Harris), that could mean the difference between one candidate, or the other, knocking down the swing states like dominoes.

None of this is to say that we will definitely have a knockout on Election Day; there’s still the very real possibility that it will be a narrow race that comes down to a few hundred votes in a single state. But understanding that these are possibilities well within the range of normal polling error may help curb some of the whiplash when the results are finally tallied.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times