THE WASHINGTON POST: Trump moves to open seabed to mining, unnerving other nations

Donald Trump has destabilised a global effort to limit mining in the deep sea, signing an executive order that could eventually open up international waters to excavation firms the US unilaterally deems worthy.

President Donald Trump on Thursday destabilised a global effort to limit mining in the deep sea, signing an executive order that could eventually open up international waters to excavation firms that the United States unilaterally deems worthy.

The idea behind the directive has already drawn strong rebukes from other countries and the UN-sanctioned agency that regulates the ocean floor in international waters. Dozens of nations involved in the effort are calling for a moratorium on deep-sea mining amid concerns that it carries dangerous, little understood environmental risks.

Such mining is currently banned, as the European Union, Russia, China and 167 other nations try to agree on how it should be regulated — or whether it should be allowed at all. But the United States is not a voting participant in those negotiations because it has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

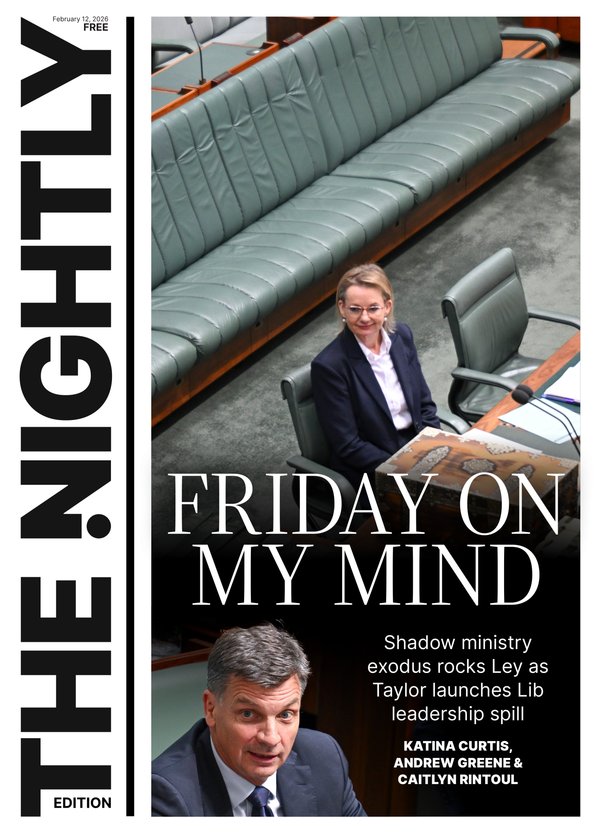

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The president’s order, which directs the commerce secretary to “expedite the process for reviewing and issuing seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits in areas beyond national jurisdiction,” comes as his administration races to find new sources of the materials key to manufacturing advanced electronics, weapons and electric vehicles.

“We expect these nodules to be used for defense, resources, infrastructure, energy purposes, all in accordance with the secretaries of energy and defense,” a senior administration official said on a background call with reporters.

“We want the US to get ahead of China in this resource space under the ocean.”

Trump’s order comes after a lobbying campaign by a Canadian firm called the Metals Co., which said in March it plans to pursue a permit from the administration through a US subsidiary.

The company has pitched investors on a plan to send robots to the seafloor to vacuum up polymetallic nodules the size of golf balls that are packed with nickel, manganese, cobalt and copper, key minerals for the production of electronics and weapons.

Trump has already signed separate orders declaring a national energy emergency and seeking to fast-track mining projects in the US But experts warn a US incursion into international waters would be fraught with diplomatic and environmental risks, while unlikely to make a dent in China’s dominance over supplies of rare minerals.

Many warn it could have the opposite effect, freeing China to pursue its own seabed-mining ambitions unshackled by the restraints of international law.

“If your concern is geopolitics and control of these resources, this puts us several steps back,” said Douglas McCauley, who heads the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

“China will beat us if we chose not to play by the sanctioned global set of rules.”

But the directive is vague on whether the US will entirely sidestep the work of the UN-sanctioned International Seabed Authority, where diplomats have been trying to forge an agreement on ocean mining for years.

It keeps that option open, but also allows for the possibility that the US could join the international effort.

The authority’s secretary general, Leticia Carvalho, warned earlier that efforts by the US to go it alone could touch off a free-for-all in which nations race to scrape the ocean for metals with little regard for environmental impact.

Scientists point to evidence of long recovery for seabeds that are mined.

A remote Pacific area thousands of miles west of Mexico subject to deep-sea mining tests in 1979 still has yet to recover ecologically and is unlikely to for decades or more, although some species have rebounded, according to a study published by the academic journal Nature last month.

Carvalho said in an email to the The Washington Post earlier this month that US permits allowing mining in waters governed by the authority would be illegal, would undermine international negotiations and “could also have broader implications for the overall stability of ocean governance.”

“Attempts to circumvent this system are not just legally unfounded — they also undermine the principles of multilateralism, transparency and collective benefit that the Convention was built to protect,” she wrote.

The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, has argued for more than a decade that, because the US is not a party to the UN oceans treaty, there is nothing legally to stop the country from deep-sea mining in international waters.

That does not mean open season for US companies to start mining anywhere in the high seas.

The US could not “unreasonably interfere in the high-seas freedoms of other nations” by intervening in other countries’ existing claims, said Heritage Foundation fellow Steven Groves.

Deep-sea mining is regulated by a 1980 US law that predates the UN treaty’s signing. Mining companies would still need to follow US laws requiring environmental impact studies, Groves said. Even under an expedited process, it could be years before the Metals Co. or any other firm gets a US permit.

The Metals Co. has for years been trying to persuade the International Seabed Authority to grant it a permit. Opposition has also come from automakers and tech companies, including Google and BMW, which have called for a moratorium on any mining of the seabed.

The authority’s member nations voted out their previous secretary general, who had starred in a Metals Co. promotional video, as concerns about the impact of harvesting the ocean floor grew globally. He was replaced by Carvalho, a Brazilian oceanographer who is seen as more receptive to the concerns of scientists.

Worries at the Metals Co. that it was running out of time and money to start vacuuming up nodules moved it to form a financial partnership with Nauru, a Pacific island that has a population of about 11,000 and is a party to the Law of the Sea.

Nauru triggered a clause in the Law of the Sea that forces the ISA to fast-track regulations on behalf of the company.

But the outlook for an ISA permit continued to dim as scientists warned the role of the nodules in the ocean ecosystem is little understood.

The nodules, which are millions of years old, are hosts to life forms that reproduce slowly and are found nowhere else. Scientists have yet to catalogue most of the life forms in the deep sea, logging with each expedition new discoveries, such as ghost octopuses and gummy squirrels.

There are also growing questions around the business logic of costly deep-sea mining.

The needs of the EV and electronics industries are constantly shifting with new innovations, and there have been major changes in battery chemistry since the Metals Co. launched its bid to mine the ocean a few years ago.

The industries need less of certain metals, causing their prices to drop and raising skepticism that it is economically practical to go through the expense of harvesting them from the far reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

The Metals Co. argues that harvesting the nodules from the seafloor would ultimately be less harmful to the environment than land-based mining that would be needed to meet the demands of the EV industry.

© 2025 , The Washington Post