SARAH STINSON: Anti-Semitism, Israel and the weight of what remains

Jerusalem doesn’t whisper its history - it bellows. In a dozen tongues. In chants, sirens, and prayers.

It is a city not so much built as unearthed - in layers of belief and grief, dust and divinity.

I began my journey at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre - the beating, bleeding heart of Christianity.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Built, razed, rebuilt, torched, and patched together like a divine jigsaw puzzle, the church has stood (or leaned precariously) since the 4th century. It is the very place many believe Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected.

Inside, six Christian denominations bicker over every broom and chapel, still bound by an Ottoman-era “status quo” that prevents them from fixing even a single step without international arbitration.

Fitting, perhaps, for a place where divinity comes with difficulty.

I lit a candle and knelt where millions before me had wept. I didn’t know what to ask for. So I simply thought of my children and family. And of peace.

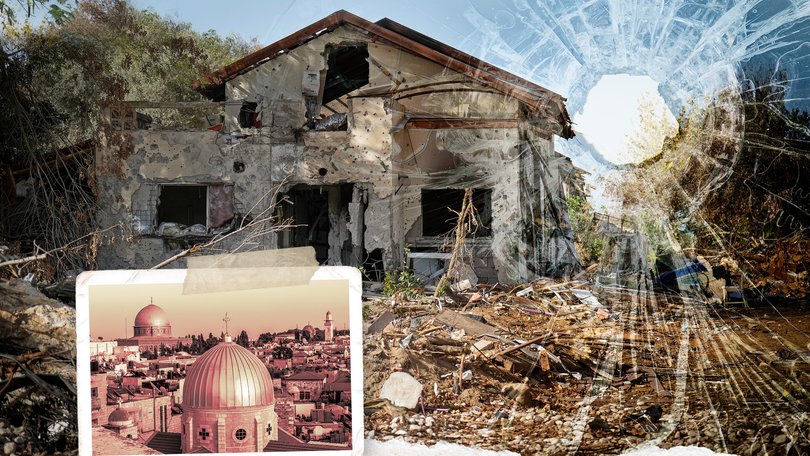

We travelled south to the Gaza Envelope - a stretch of land that hugs the border with Gaza. Life here carries on beneath a sky that never fully relaxes.

They call this area the “envelope” because these towns and kibbutzim wrap around Gaza’s northern and eastern edge - close enough to be shaped by rocket fire, tunnel incursions, and cross-border raids.

Sirens here mean you have 15 seconds. Fifteen seconds to get to shelter. Residents live in that rhythm - physically, emotionally, psychologically.

Nothing prepared me for Kibbutz Be’eri. Over 100 people were killed. Six are still missing.

Survivor Danny Majzner showed us around like a curator of trauma. Bullet holes in children’s bedrooms. Toys still on floors. Empty playgrounds.

Danny didn’t speak with rage - only a stunned disbelief that such horror could unfold in a place once called paradise. In homes with mezuzahs on the doors and family portraits still smiling from the walls.

Onto Sderot, a small Israeli town that sits less than a kilometre from the border. Here, children learn to sprint to bomb shelters before they learn to read. That’s not resilience. That’s conditioning.

Just beyond the fence, in Gaza, there is devastation too. Families buried beneath rubble. Parents desperately trying to protect their little ones with nothing but their bodies and prayers.

Many live not only under bombardment - but under the brutal grip of Hamas, a regime that uses its own people as shields and silences dissent with fear. The grief here does not cancel out the grief there. It echoes it.

Mirrors it.

On both sides of the border, people wake each day to a reality shaped by fear and the unbearable uncertainty of who won’t come home. It’s impossible not to feel the ache of that truth pressing in from every direction.

At the Nova festival site, where music once pulsed and freedom reigned, silence now lingers.

Three hundred and sixty-four lives were taken on October 7 - mid-laugh, mid-song.

Some victims were hunted across open fields. Others burned, tortured, abducted. It was the worst civilian massacre in Israel’s history.

We met a young survivor and a Muslim Bedouin man whose bravery saved his and other Jewish lives.

I didn’t know it then, but later we would sit with an IDF rep and view 47 excruciating minutes of footage taken from that day. I can’t write about it. Not yet. Some things settle too deep for words.

As we stood on that haunted ground, the sound of missiles rumbled overhead - as if the threat still danced long after the music stopped.

We met Ayelet Razin back in Jerusalem - a senior official from Israel’s Ministry of Justice and a leading voice on gender-based violence.

She spoke with quiet fury.

“This wasn’t random,” she said. “It was systematic. It was weaponised.”

In Majdal Shams, a Druze village in the Golan Heights bordering on Syria, we stood on a scorched soccer field where twelve children were killed in a terror attack. They died running for shelter.

The youngest was ten.

Their photographs now hang on twisted wire fences - eyes wide with innocence that never got to ask why.

Their fathers stood beside them. Not calling for revenge. Just asking for peace.

That kind of restraint is difficult to witness. Harder still to forget.

I wanted to hide my tears and look away, but you don’t look away from courage like that.

It wasn’t until I visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s holocaust memorial and museum, that I felt the full depth of generational grief.

The museum doesn’t shout. It doesn’t need to.

The shoes. The suitcases. The photographs - entire families, smiles too unguarded to know what was coming.

The Children’s Memorial is unlike anything I’ve experienced.

A darkened space filled with candlelight and whispered names, reflected endlessly in mirrors to mimic a star-filled sky.

Each flicker, a life extinguished.

I thought I understood anti-Semitism. I thought it lived in the past.

But in Israel, I felt its weight - not as theory, but inheritance.

Fear worn like an extra layer of skin. Mothers keeping shoes by the door.

Anti-Semitism isn’t history. It’s a pulse - steady, quiet, sometimes violent - across the world.

I finally understood why “Never Again” isn’t a slogan. It’s a plea.

And beneath the grit, grief, and guarded hearts, I felt something else: A quiet, aching loneliness. Israelis who feel misread by a world quick to judge but slow to understand the weight they carry and the war they never wanted.

One night in Tel Aviv, a missile siren pierced the calm. We walked briskly into a nearby shelter that happened to be the women’s bathroom.

Inside, strangers stood shoulder to shoulder.

A young man looked at us, smiled gently. “It will be okay.”

It wasn’t optimism. It was survival instinct.

We waited. Word came.

The missile from Yemen was intercepted.

I asked the man, “What if it hadn’t been?”

He shrugged and said one word: “Boom” with the finality of someone who’s run out of ways to explain war to people who haven’t lived it.

And then, the moment I keep replaying on a loop.

I sat opposite a mother - Viki Cohen.

Her 20-year-old son, Nimrod, was taken on October 7.

She knows he’s alive.

She wakes each day not knowing what or if he’s eaten, if he’s warm, if he’s scared, if he’s safe.

But she shows up. Every day. Protesting. Hoping.

“Who wouldn’t do this?” she said. “I am his mother.”

She proudly told us about her beautiful gentle son and the ongoing impact on his twin sister who yearns for him every second.

“He will always be my baby. I just want him home.”

During our visit, Israeli President Isaac Herzog publicly called on Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to come to Israel - not just for diplomacy, but to see. Truly see.

The trauma. The families torn apart. The children missing. The fear that echoes long after the headlines move on.

But even as he spoke, I kept thinking of all the children - Israeli, Palestinian, and beyond - who are caught in the crossfire of grown-up wars.

Children always pay first. And longest.

We owe them more than sides.

We owe them safety.

We owe them peace.

On our final night, we were welcomed into a Tel Aviv home for Shabbat.

As Hebrew blessings filled the air, the Muslim call to prayer rang out across the city.

For one brief moment, the two rose together - a duet of devotion.

Peace, in counterpoint.

It didn’t last. But it reminded me that it can.

This trip didn’t change how I see politics.

It changed how I see pain. And courage. And survival.

It changed how I understand hatred.

And why the people here live with one hand on hope and the other on history.

Because in Israel, both are necessary.

And I kept thinking of where this journey began - kneeling in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, surrounded by centuries of suffering and salvation.

A place built on resurrection.

Weathered.

Wounded.

Still standing.

Just like this land.

Just like its people.

Fragile, yes - but unyielding.

Fiercely full of faith.

Still reaching toward the light.

Maybe that’s what hope really means here.

Not just believing peace is possible, but making the quiet, daily choice to build toward it anyway.

And now, I head home heart heavier, eyes wider to do the one thing denied to so many here:

Hug my babies.

Tighter than before. And never without gratitude.

To tuck them in, and whisper what too many mothers still can’t.

You’re safe.

Sarah Stinson visited Israel courtesy of the AIJAC

Sarah Stinson is the Seven Network’s Director of Morning Television