THE ECONOMIST: Canada’s Conservatives are crushing Justin Trudeau

“How is my life better?” demands Kareem Lewis, a 32-year-old Canadian software engineer, after almost a decade of Liberal government.

“Real wages are flat. The cost of rent as a proportion of your income has increased,” he says. And forget about buying a house. Fed up, he has moved to New York. Always a Liberal backer, he will vote Conservative in the election due next year.

Pierre Poilievre, the Conservative leader, is attracting other unlikely voters, too. He has spent much of the summer in factories from British Columbia to Newfoundland, surrounded by employees in hard hats and safety glasses, to cement his lead among working-class voters.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

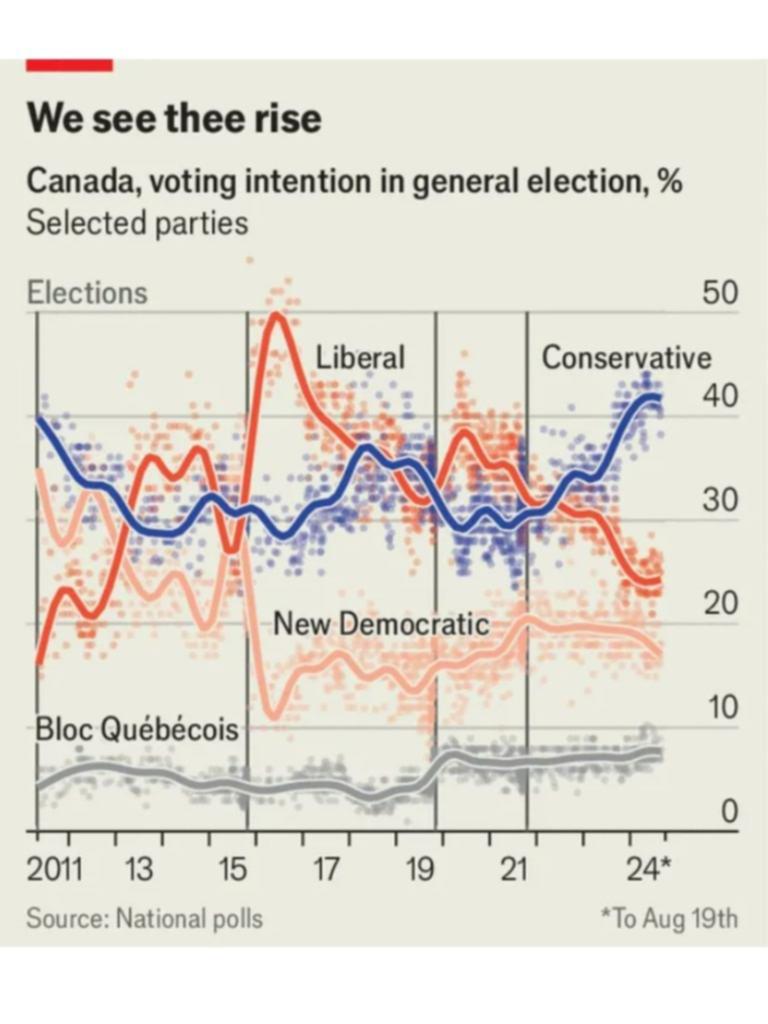

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.When Mr Poilievre won the leadership of the party in September 2022, the Conservatives were tied with the Liberals, led by Justin Trudeau, the prime minister. Today the Conservatives have a 17-point lead (see chart). The party has not polled this well since 1988.

Many of Mr Poilievre’s plans are still foggy, but he has built his popularity on a pair of issues that bother swathes of the electorate: inflation and a drum-tight housing market strained by millions of immigrants. He couples this with a well-honed pitch to young voters and relentless hard-hat-heavy signals that he feels for working people’s troubles. That Mr Trudeau has a net personal approval rating of minus 35 helps, too.

The 45-year-old Mr Poilievre can seem beset by contradictions. He has never held a full-time job outside politics, yet he rails against political insiders.

Despite leading the traditional party of business, he did not criticise rail workers for a recent strike that threatened to disrupt the supply of goods across North America.

Though he shares Donald Trump’s bombastic style and scorn for the mainstream media, unlike Mr Trump he strongly backs Ukraine and vows never to restrict access to abortion. The fact these tensions seem to help him testifies to his political skill and to his credibility on the two big issues.

The first is inflation. Ahead of other Canadian political leaders, he identified the despair of younger Canadians and the frustrations of working-class voters during the sudden bust of the pandemic and the inflation-fuelled property boom that followed. That put him at odds with the governor of the Bank of Canada, Tiff Macklem, who suggested that inflation was transitory. When Mr Poilievre’s prediction of prolonged high inflation proved right, he pushed for Mr Macklem’s sacking.

His second strong card is over immigration and housing. More than 471,000 permanent residents were admitted to Canada in 2023, the highest annual increase in the country’s history. Add to this the roughly one million student visas issued last year and an even larger number of temporary work permits granted. All of this strains public services and Canada’s housing market, both big worries for voters.

In Europe some right-wing parties have drifted into immigrant-bashing. Mr Trump still boasts of his “Muslim ban”. Mr Poilievre, whose wife was born in Venezuela, is careful to avoid alienating voters in the politically crucial multiracial suburbs of Toronto.

Instead he frames the issue as a numbers game. He says he will tie the number of newcomers to the rate of new homes built each year. Last year some 240,000 homes went up, so his policy would mean a sharp cut in immigration.

The plan polls so well that even Mr Trudeau has put in a new minister for immigration — and has vowed to cut it.

To help increase the supply of housing Mr Poilievre would reward cities with federal money if they build more homes. Fail to increase permits for home building by at least 15 per cent and they would lose grants.

Federal money for public transport would depend on building high-density housing near stations. His plan has been panned as unworkable by federal bureaucrats for failing to take renters into account, according to documents obtained by the Toronto Star, a newspaper. Mr Poilievre has a ready retort: incompetent bureaucratic “gatekeepers” in big cities are preventing younger Canadians from owning their own homes.

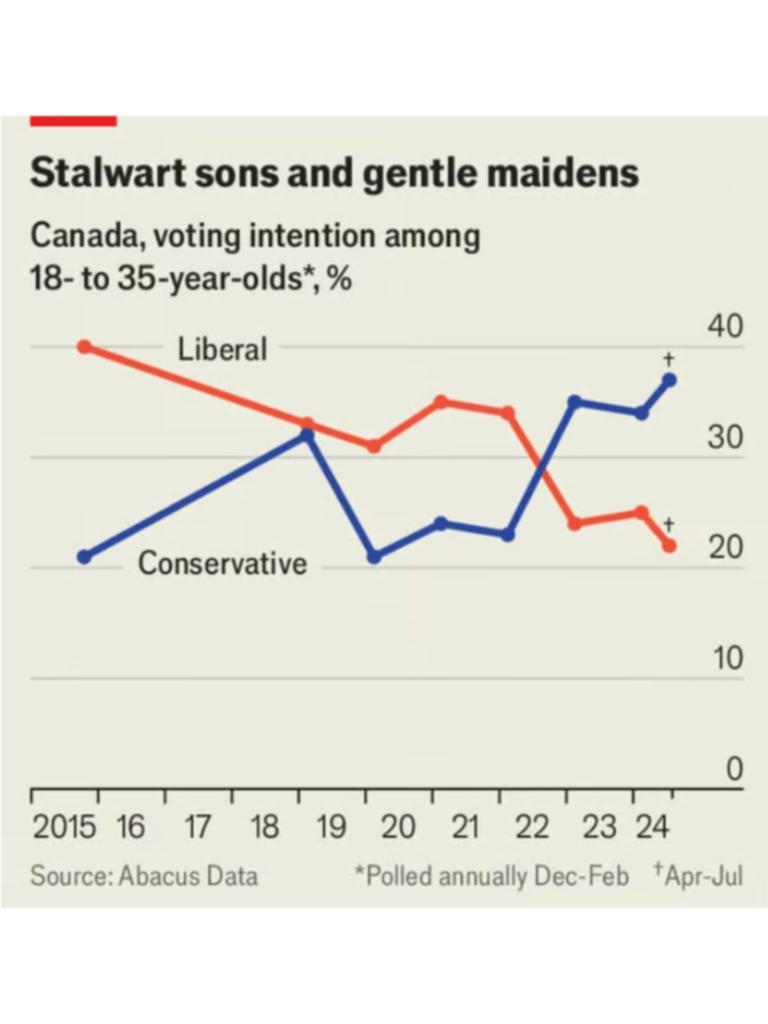

Thanks in large part to this issue, the Conservatives now lead by 15 percentage points among voters aged 18 to 35, a sharp reversal of traditional patterns. That lead opened up once Mr Poilievre began to attack Mr Trudeau over the 66 per cent rise in house prices since the Liberals were elected in 2015.

That year there was an unprecedented increase in first-time voters. Many were attracted to Mr Trudeau’s promise to legalise marijuana use and to bring down carbon emissions. Young voters now care a lot more about moving out of their parents’ basements and eventually buying a home.

“Home ownership just seems so unreachable,” laments Justin Lee, a 25-year-old also switching from Liberal to Conservative.

Mr Poilievre has aggressively courted working-class voters. He still recites some of the priorities of a corporate conservative, offering broad-based tax relief including tax cuts for big business, without clarifying how these will be paid for. He has also vowed to scrap the carbon tax, currently C$80 ($59) per tonne. And he says he will make it easier to exploit Canada’s vast oil and gas resources.

Yet he told a blue-chip audience of bosses earlier this year that he is not interested in meeting them for lunch at plush private clubs and would rather talk to workers on factory floors. His “daily obsession” as prime minister would be, he said, “about what is good for the working class of people in this country”. He would ban his ministers from attending the elite gabfests in the Swiss resort of Davos.

Pin-striped Tories, with nowhere else to go, are sticking with him.

But he not only offers selfies among hard hats. Earlier this year he supported legislation that bans strike-hit companies from taking on replacement workers. That is a big change for a man who in 2012 proposed ending the compulsory collection of union dues from non-members in unionised workplaces.

Bea Bruske, head of the Canadian Labour Congress, a big union, points out that Mr Poilievre has never walked a picket line and calls him a “fraud”. But her members seem to differ.

A survey of private-union members by Abacus Data, a pollster, suggests that 43 per cent back the Conservatives compared with 24 per cent for the Liberals.

“The centre of Conservative gravity is no longer the entrepreneur,” says Sean Speer, a policy adviser to the last Conservative government.

“It’s the wage earner.”

A general election is not expected for about a year. Much disdain for the Liberals is tied to Mr Trudeau, stoking rumours he could step aside. Some hope that Mark Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England, might replace him.

Interest-rate cuts and a dramatic economic recovery could yet help the Liberals. But if Mr Poilievre can keep his unlikely coalition together for another year, a thumping victory will surely be his.