THE ECONOMIST: Do tariffs like Donald Trump’s raise inflation?

Usually. But the bigger problem is that they harm economic growth and innovation.

Mountain-naming turned out to be a curiously high priority for Donald Trump. Mere hours after his inauguration, the President signed an executive order to change the name of America’s highest peak from Mount Denali, of Indigenous Alaskan origin, back to Mount McKinley, as it was officially known until Barack Obama intervened in 2015.

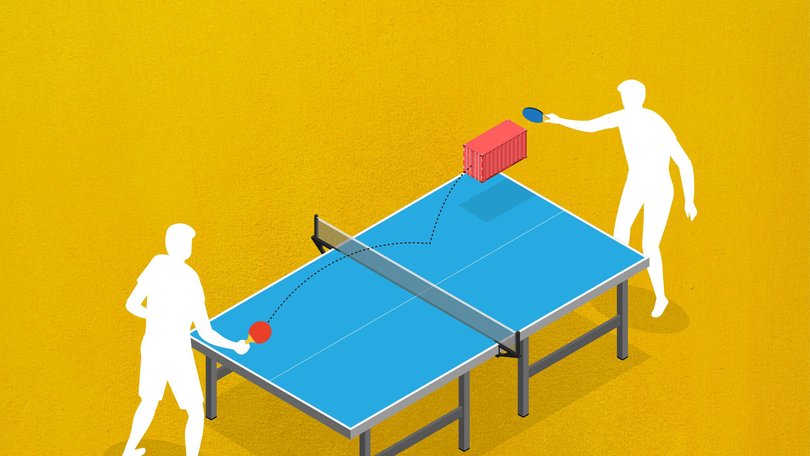

The rechristening reflects more than just the usual culture-war ping-pong. Like Mr Trump, William McKinley was a “tariff man”. As a congressman and later president, he swung America toward protectionism in the late 19th century.

“President McKinley made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent,” said Mr Trump in his inaugural address.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Over a century later, Mr Trump hopes to pull off the same trick. His raft of day-one executive orders did not institute any new tariffs, focusing on mountains, a border emergency, drilling for oil and halting DEI programmes. But the President still found time to threaten a 10 per cent tariff on China, as well as a 25 per cent tariff on Canada and Mexico, to be introduced as soon as February 1. He also floated a “global supplemental tariff”, which would apply to any good imported from abroad, no matter its country of origin.

Higher tariffs, Mr Trump and his backers say, will boost American manufacturing and fund tax cuts at little cost to the every man, with foreigners footing the bill instead. These justifications are feeble, just as they were in McKinley’s day. For a start, firms usually pass on tariffs by raising prices. During Mr Trump’s last sortie against Chinese manufacturing in 2018-19, prices of impacted items went up roughly one-for-one with higher tariffs.

Mr Trump’s more thoughtful advisers, such as Scott Bessent, nominated for treasury secretary, and Stephen Miran, for chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, accept this dynamic. But they emphasise that tariffs also strengthen the dollar by pushing Americans to purchase less from abroad.

This lifts their purchasing power and so should help cancel out higher prices. Exchange rates depend on much more than goods trade, so the effect of tariffs during Mr Trump’s first term was small. In 2018-19, for instance, they explain at most a fifth of the move in the dollar over the period, according to Olivier Jeanne and Jeongwon Son of Johns Hopkins University. Bigger tariffs would have bigger effects.

Yet even if the dollar rises, the pain simply shifts to exporters, whose wares become more expensive for international buyers (which is why Mr Trump usually favours a weaker dollar). For his part, Mr Miran argued in a recent paper that the greenback’s popularity imposes “externalities” on America’s economy, since demand for assets yanks the dollar above its fair value, hobbling exporters in the process.

This theory is questionable on its own merits. The big deficits that recent administrations have run could not have been financed so cheaply without a queue of foreigners buying Treasury bonds. Moreover, if Mr Miran had his way, any boost to the dollar from tariffs would be short-lived: a dollar devaluation would once again leave households facing higher prices.

Tariff-boosters also downplay the odds that other countries will respond in kind. And patience, even among allies, is already wearing thin. “One tariff would be followed by another,” warned Claudia Sheinbaum, president of Mexico, in November. Justin Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, has vowed “robust, rapid” retaliation. Such moves would pull the dollar in opposing directions: American demand for imports from abroad would fall, but so would foreign demand for American exports. All told, American households would be left with little insulation from tariffs.

So tariffs raise prices. Does that mean they cause painful inflation? Not necessarily. A one-off increase in prices might create only a short-term pop in inflation, not a sustained rise.

Tariffs erode consumers’ overall spending power, and falling consumption of things produced at home creates offsetting disinflation over time. Yet there is at least a danger that a one-off shock would set off an upwards spiral of prices and wages. After several years of high inflation, such a risk is now more pronounced.

Mountainous problems

Worse still, tariffs also crimp economic growth by creating “deadweight loss”, as demand is skewed towards domestic companies even when they are less efficient. As a consequence, resources are wasted on production that is more expensive than it otherwise would have been. The result is a vast economic distortion and lower incomes throughout the economy.

This effect is exacerbated by the fact that tariffs induce companies to innovate less and misbehave more. Sheltered from better-run foreign rivals, firms have less incentive to produce superior and cheaper products. Alla Lileeva of York University and Daniel Trefler of the University of Toronto have found that reductions in American tariffs in the late 1980s and 1990s prompted previously less productive factories in Canada to innovate more, adopt advanced technology and, as a result, increase the productivity of their workers.

Tariff regimes also tend to be chock-full of exemptions, which the savviest firms learn to exploit, at the same time as their lobbyists seek more carve-outs. Mr Trump’s love of doling out favours could cause a particular problem in this regard.

Over the course of his political career, McKinley’s own enthusiasm for protectionism softened. Although America’s 25th president never transformed into a free-trader of The Economist’s variety, he did come to appreciate the benefits of mutually advantageous trade deals with friendly countries.

“We must not repose in fancied security that we can for ever sell everything and buy little or nothing,” he announced in Buffalo, New York, in 1901, before adding that “commercial wars are unprofitable”. America’s 45th and 47th president has perhaps not learned the correct lessons from his predecessor.