THE WASHINGTON POST: Surgeon removed wrong organ then covered it up, widow alleges in suit

THE WASHINGTON POST: Beverly Bryan alleges a surgeon killed her husband by mistakenly removing his liver instead of his spleen, then participated in a conspiracy.

Beverly Bryan was confident on Aug. 21 as her husband headed to surgery to have his spleen removed at a Florida hospital.

Bryan, a retired registered nurse, knew the procedure — a laparoscopic splenectomy — was safe, and the surgeon assured her “it would be quick and over and done.”

“You’ll see him back in a few minutes,” she recalled the doctor saying.

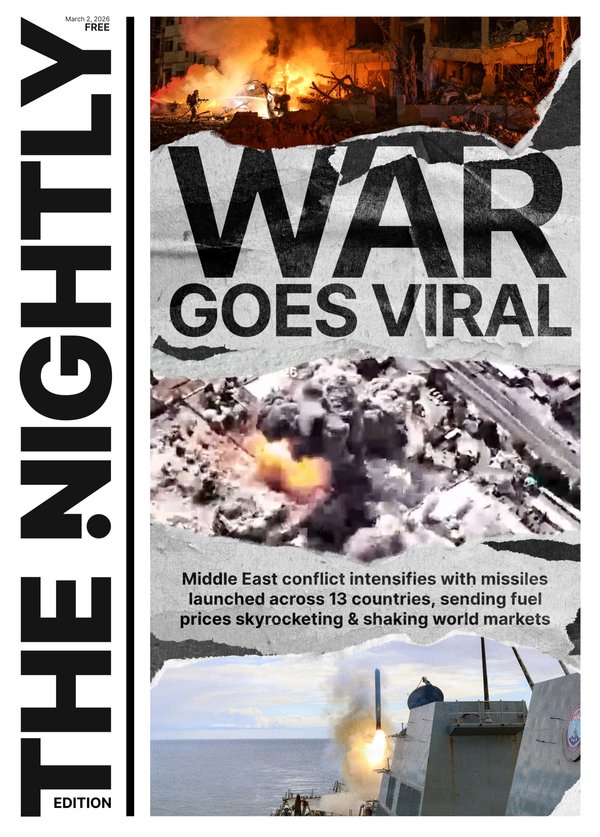

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It was the last time she saw her husband alive.

Now, nearly six months later, Bryan is suing the surgeon, Thomas J. Shaknovsky, and the hospital where he operated on her husband, accusing them of wrongful death and medical malpractice.

In a 114-page complaint filed on Jan. 30 in Florida’s First Judicial Circuit Court in Walton County, Bryan alleges that Shaknovsky killed her husband by mistakenly removing his liver instead of his spleen, then participated in a conspiracy — that included the hospital’s CEO and chief medical officer — to cover up the fatal error by doctoring the death certificate and other state records.

Bryan, 70, is also accusing Ascension Sacred Heart Emerald Coast Hospital in Miramar Beach, Florida, of employing the services of a doctor who, before operating on Bryan’s husband, had repeatedly made serious mistakes, including one in 2023 in which he also operated on the wrong organ. That incident, according to state records, resulted in a $400,000 settlement.

Bryan said she researched Shaknovsky and Ascension beforehand but found few if any red flags. She wants her lawsuit to spur lawmakers and others to make it easier for patients to discover doctors’ wrongdoing, complaints and malpractice settlements.

“It really needs to be more transparent when doctors have a bad history,” she said.

Shaknovsky did not respond to requests from The Washington Post to talk about Bryan’s allegations but told state investigators he couldn’t properly identify the organ he removed because of “his shock and the chaos of the situation” but assumed it was the spleen.

Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo determined in September that Shaknovsky was being “deceptive and untrue” during the interview and immediately suspended his medical license.

Ascension Sacred Heart spokesman Gary Nevolis declined to comment.

High-pressure situation

On Aug. 18, Bryan and her husband, Bill, who live in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, were visiting their rental property in the Florida Panhandle when Bill, who was 70 at the time, started experiencing pain in his shoulder, she said. Thinking it would subside, he tried to wait it out, but as it spread down the left side of his body, his wife encouraged him to return home, she said. He balked because Beverly couldn’t load their truck without his help.

As the pain persisted, the Bryans went to a fire station down the street where paramedics took his blood pressure, the results of which led them to Ascension’s emergency department, Bryan said. Doctors there admitted Bill, and on Aug. 19, an MRI exam of his abdomen and pelvis revealed that something was wrong with his spleen, Bryan’s lawyer, Joseph Zarzaur Jr., said in the lawsuit.

Shaknovsky, the hospital’s on-call surgeon, recommended removing the spleen, the suit alleges. The Bryans initially rejected his recommendation, requesting a transfer to a hospital that could provide a higher level of care, according to the suit. Bryan said she wanted to take her husband home to Muscle Shoals, where they could get better care from their normal doctors in nearby Florence.

Shaknovsky warned that Bill risked bleeding to death if he left the hospital to make the nearly 400-mile journey to northwest Alabama, the suit states. For two days, Shaknovsky and others at the hospital allegedly pressured the Bryans to let them do the procedure until they relented.

At 4:18 p.m. on Aug. 21, Bryan signed a consent form for her husband to have laparoscopic surgery, and Shaknovsky started the procedure about 1½ hours later, the suit states. In the meantime, several surgical staffers allegedly told the hospital’s chief medical officer, Joseph Bacani, that they were worried about doing the procedure at Ascension’s limited facilities and warned that they thought Shaknovsky was not skilled enough to perform it.

Bacani “did nothing to stop or alter this procedure in any way,” the complaint alleges.

An alleged cover-up

At 5:48 p.m., Shaknovsky and his team started the surgery, the suit states. Although the procedure was supposed to be a laparoscopic splenectomy, a minimally invasive process requiring a few small incisions, Shaknovsky switched to open surgery because of poor visibility, according to the lawsuit and state disciplinary records.

Several staff members watched Shaknovsky operate on the right side of Bryan’s body, the opposite side of where the spleen is normally located, the suit states. Instead of removing Bryan’s spleen, Shaknovsky took out his liver, severing a major vein and causing devastating blood loss that killed Bryan, a prosecutor with Florida’s Department Health alleged in a petition to revoke Shaknovsky’s medical license.

Handing the organ to nurse Tammy Nelson, Shaknovsky told her to mark it “spleen,” even though it weighed at least 10 times as much as the average spleen and was clearly a liver, according to Bryan’s lawsuit. Nelson allegedly did as she was told.

Within minutes, other doctors and hospital higher-ups swarmed the operating room, the suit states. All of them allegedly recognized the organ that had been removed was a liver but nevertheless covered up Shaknovsky’s mistake by documenting on official records that he had cut out Bryan’s spleen.

Shaknovsky allegedly tried to persuade hospital staff members that it was the spleen. He repeatedly left and returned to the operating room to tell people that Bryan had died of a “splenic aneurysm,” the suit states. In informing Bryan of her husband’s death, he allegedly told her the cause was a spleen so diseased that it had swelled to four times the normal size and shifted to the other side of his body.

Ascension nurse Kathleen Montag chased Bryan into the parking lot and lied about how her husband had died to get her signature agreeing to forgo an autopsy, the suit states.

The cover-up fell apart when the district’s medical examiner performed an autopsy and determined that the organ that had been removed was Bryan’s liver while his spleen was untouched and in the normal position, state disciplinary records show. The medical examiner ruled Bryan’s death a homicide caused by bleeding to death and having his liver removed.

On Sept. 24, Ladapo, Florida’s surgeon general, ordered an emergency suspension of Shaknovsky’s medical license, citing not only Bryan’s botched splenectomy but also a 2023 procedure in which he allegedly removed part of a 58-year-old patient’s pancreas instead of cutting out a portion of their adrenal gland as intended.

The following month, medical officials in Alabama revoked his license there, Bryan’s suit states.

Records from Florida’s health department show that Shaknovsky’s license status was “retired” as of Nov. 14.

‘Almost unbearable’

Bryan said it was “disheartening” to be so devastatingly disabused of her presumption that people can trust doctors and hospitals. Part of her mission, she said, is to make sure patients and their family members can more easily discover information that affects their health and their lives.

“Bill would want everybody to know about his death,” Bryan said, “because … it’s so hard to find out about a physician’s past.”

Bryan kept her composure while recounting what happened leading up to and after her husband’s death — the times and dates, her discussions with Bill about his health care, the conversations they allegedly had with Shaknovsky, and what she’s learned since as she and her lawyer have investigated his death.

But she broke down while talking about what she’s lost: Bill himself, a realization she said has only recently hit her. The sounds he made around the house (it’s so quiet now), the sense of security he provided (she learned how to shoot a gun after he died), the bike rides they took together (she doesn’t ride as much these days). And more than anything, the good, kind and friendly person who did things such as take in and take care of Bryan’s mother for 11 years as she irreversibly spiraled into the depths of dementia - and then died.

Bryan couldn’t get through listing even a few examples without her voice rising and then cracking.

“The loss of his companionship,” she said through halting sobs, “is almost unbearable.”

© 2025 , The Washington Post