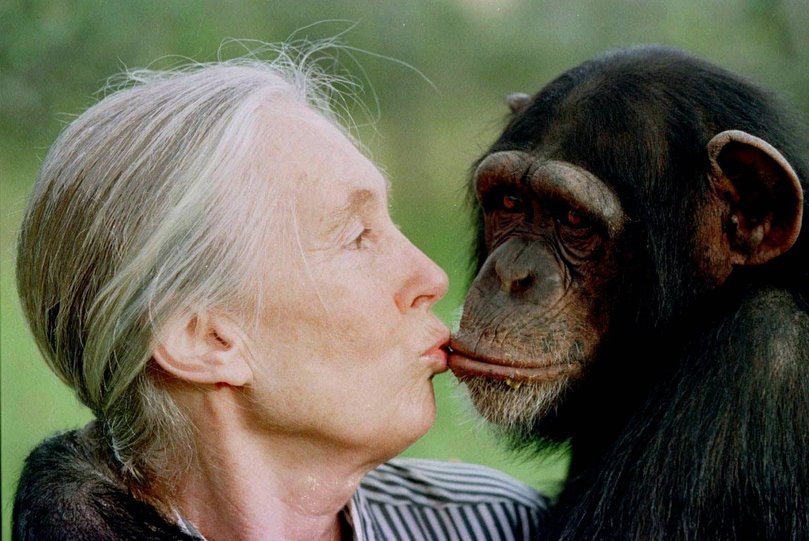

Jane Goodall, eminent primatologist who chronicled the lives of chimps, dies at 91

Her discoveries as a primatologist in the 1960s about how chimpanzees behave in the wild broke new ground and were hailed as ‘one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements’.

Jane Goodall, one of the world’s most revered conservationists, who earned scientific stature and global celebrity by chronicling the distinctive behaviour of wild chimpanzees in East Africa — primates that made and used tools, ate meat, held rain dances and engaged in organized warfare — died Wednesday, local time, in Los Angeles. She was 91.

Her death, while on a speaking tour, was confirmed by the Jane Goodall Institute, whose US headquarters are in Washington, DC.

The British-born Dr Goodall was 29 in the summer of 1963 when the National Geographic Society, which was financially supporting her field studies in the Gombe Stream Chimpanzee Reserve in what is now Tanzania, published her 7,500-word, 37-page account of the lives of Flo, David Greybeard, Fifi and other members of the troop of primates she had observed.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The article, with photographs by Hugo van Lawick, a Dutch wildlife photographer whom she later married, also described her struggles to overcome disease, predators and frustration as she tried to get close to the chimps, working from a primitive research station along the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika.

On the scientific merits alone, Dr Goodall’s discoveries about how wild chimpanzees raised their young, established leadership, socialized and communicated broke new ground and attracted immense attention and respect among researchers. Stephen Jay Gould, an evolutionary biologist and science historian, said her work with chimpanzees “represents one of the Western world’s great scientific achievements.”

On learning of Dr Goodall’s documented evidence that humans were not the only creatures capable of making and using tools, Louis Leakey, a paleoanthropologist and Goodall’s mentor, famously remarked, “Now we must redefine ‘tool,’ redefine ‘man,’ or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

Long before focus groups, message discipline and communications plans became crucial tools in advancing high-profile careers and alerting the world to significant discoveries in and outside of science, Dr Goodall understood the benefits of being the principal narrator and star of her own story of discovery.

In articles and books, her lucid prose carried vivid descriptions, some lighthearted, of the numerous perils she encountered in the African rainforest — malaria, leopards, crocodiles, spitting cobras and deadly giant centipedes, to name a few. Her writing gained its widest attention in three more long articles in National Geographic in the 1960s and ’70s and in three well-received books, My Friends, the Wild Chimpanzees (1967), In the Shadow of Man (1971) and Through a Window (1990).

Dr Goodall’s willingness to challenge scientific convention and shape the details of her arduous research into a riveting adventure narrative about two primary subjects — the chimps and herself — turned her into a household name, in no small part thanks to the power of television.

Dr Goodall’s gentle, knowledgeable demeanour and telegenic presence — set against the beautiful yet dangerous Gombe preserve and its playful and unpredictable primates — proved irresistible to the networks. In December 1965, CBS News broadcast a documentary of her work in prime time, the first in a long string of nationally and internationally televised special reports about the chimpanzees of Gombe and the courageous woman steadfastly chronicling what she called their “rich emotional life.”

And in becoming one of the most famous scientists of the 20th century, Dr Goodall opened the door for more women in her largely male field as well as across all of science. Women — including Dian Fossey, Biruté Galdikas, Cheryl Knott and Penny Patterson — came to dominate the field of primate behaviour research.

Most of Goodall’s observations focused on several generations of a troop of 30 to 40 chimpanzees, the species genetically closest to humans. She named and grew to know each of them personally. She was particularly interested in their courtship, mating rituals, births and parenting.

Goodall was the first scientist to explain to the world that chimpanzee mothers are capable of giving birth only once every 4 1/2 to 6 years, and that only one or two babies were produced each year by the Gombe Stream troop. She found that first-time mothers generally hid their babies from the adult males, prompting frantic displays by the males — leaping and hooting that could last five minutes. An experienced mother, however, she discovered, freely allowed males and other females to view her infant, satisfying their curiosity, in a far calmer introduction.

In her many articles, books and documentaries, Dr Goodall explored similar signal moments in her own life. In March 1964, after a nearly yearlong courtship, she married van Lawick. Three years later, she gave birth to Hugo Eric Louis van Lawick, her only child, whom she nicknamed Grub.

But even there she drew connections to her work in the field. She explained that her parenting philosophy and strategy were based on skills and values that she had learned from the chimpanzees, particularly the sure-handed matriarch of the troop, whom she named Flo. Nevertheless, she kept Grub in a protective cage while she was in the forest with him: She feared that he might be killed and eaten by the chimps.

Dr Goodall’s ability to weave scientific observation with the story of her own life produced a powerful drama filled with characters of all ages, sexes and species. She once told a scientific meeting that her work would have had far less resonance scientifically or emotionally if she had just referred to the proud and confident chimp known as David Greybeard by a number, as was the usual practice.

In the 1970s, Goodall began to spend less time observing chimpanzees and far more time seeking to protect them and their disappearing habitat. She made known her opposition to capturing wild chimpanzees for display in zoos or for medical research. And she traveled the world, drawing large audiences with a message of hope and confidence that the world would recognize the importance of preserving its natural resources.

The 1970s were also a period of upheaval in her personal life. In 1974, she divorced Mr van Lawick and soon afterward married Derek Bryceson, the director of national parks in Tanzania. He died of cancer in 1980, a time she later said was perhaps the most difficult of her life.

She established the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977. It evolved into one of the world’s largest nonprofit global research and conservation organizations, with offices in the United States and 34 other nations. Its Roots and Shoots program, launched in 1991, teaches young people about conservation in 120 countries.

In honour of her work, Tanzania in 1978 designated the Gombe Stream Reserve a national park. Dr Goodall’s institute maintains a research station there that attracts students and scientists from around the world. In 2002, the United Nations named Goodall a Messenger of Peace, the UN’s highest honour for global citizenship.

Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in London on April 4, 1934, and raised in Bournemouth, on the south coast of England, the older of two girls of Margaret Myfanwe (Joseph) Goodall, who was known as Vanne, and Mortimer Herbert Morris-Goodall. Her mother was an author and novelist who wrote under the name Vanne Morris-Goodall. Her father was an engineer who raced cars for a time. The couple divorced after World War II. Vanne Goodall accompanied her daughter to the Gombe reserve at the start of Jane Goodall’s famous study in 1960 and was a leading character in much of her daughter’s writing.

As a little girl, Dr Goodall adored Tarzan’s Jane, Dr Doolittle and a little stuffed monkey doll, a gift from her father that she named Jubilee. In the more than 300 public appearances she made around the world each year in her last decades, Dr Goodall almost always described her scientific findings and international renown as a fortunate convergence of her childhood love of animals and Africa with her inquisitive and adventurous nature.

In 1956, after finishing a course in secretarial school and taking several jobs in London, she received a letter from a friend whose family owned a farm near Nairobi, Kenya. The friend invited her to join her.

Dr Goodall jumped at the opportunity. Booking passage on a freighter to Africa, she arrived in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, on her 23rd birthday. She was soon introduced to other expatriate Englishmen and women in Nairobi as well as to Dr Leakey, at the time a prominent but not yet internationally renowned archaeologist.

Seven weeks after her arrival, she began work as Dr Leakey’s secretary and assistant. Dr Goodall accompanied him that summer to the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, a three-day trip over trackless wilderness, where he was in the early phases of excavating early human remains. He often talked about his interest in stationing a researcher on Lake Tanganyika to study a troop of wild chimpanzees that lived there.

Those discussions led to an agreement with Dr Goodall that she would take on that mission. On July 14, 1960, accompanied by her mother, she arrived at Gombe, and three months later, she watched as the big, handsome adult male chimp she named David Greybeard did something no human had ever expected of an animal.

“He was squatting beside the red earth mound of a termite nest, and as I watched I saw him carefully push a long grass stem down into a hole in the mound,” she wrote. “After a moment he withdrew it and picked something from the end of it with his mouth. It was obvious that he was actually using a grass stem as a tool.”

Recognizing the contributions she was making to science, the University of Cambridge accepted her into its doctoral program in 1961 without an undergraduate degree. She was awarded her doctorate in 1965.

Dr Goodall wrote 32 books, 15 of them for children. In her last book, The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times (2021, with Douglas Abrams and Gail Hudson), she wrote of her optimism about the future of humankind.

Her many awards include the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal, presented in 1995, and the Templeton Prize, given in 2021. In 2003, Queen Elizabeth II named her a dame of the British Empire. In January, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest civilian honour, by President Joe Biden.

She is survived by her son; her sister, Judy Waters; and three grandchildren.

In July 2022, Mattel released a Jane Goodall doll as part of its Barbie-branded Inspiring Women series. The doll, with blond hair and dressed in a tan field shirt and shorts, is made of recycled plastic. It honoured the 62nd anniversary of Dr Goodall’s first visit to the Gombe reserve.

“Since young girls began reading about my early life and my career with the chimps, many, many, many of them have told me that they went into conservation or animal behaviour because of me,” Dr Goodall once said in a CBS News interview. “I sincerely hope that it will help to create more interest and fascination in the natural world.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times