THE WASHINGTON POST: New look at ancient skull challenges timeline of human evolution

THE WASHINGTON POST: An ancient skull is challenging the textbook timeline of human evolution, prompting some scientists to argue that our own species is much older than previously thought.

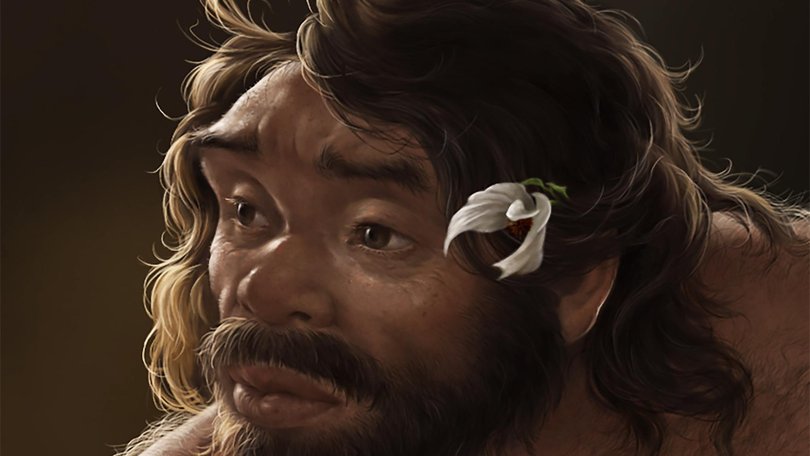

He lived hundreds of thousands of years ago, eking out an existence in what is today central China. Sporting a squat neck and a big brain, he likely wielded tools made of stone and hunted or scavenged for ancient ungulates, elephants and rhinos.

Now this ancient man — or least, his fossilised skull — is challenging the textbook timeline of human evolution, prompting some scientists to argue that our own species is much older than previously thought.

A fresh analysis of this male cranium, published Thursday in the journal Science, suggests modern humans split from Neanderthals and other archaic humans more than a million years ago. The findings call into question the usual date of 500,000 to 700,000 years ago for when this last common ancestor lived.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“That’s a big change,” said Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London and co-author of the study. “We’re talking about something maybe double that for the divergence of those groups.”

But other researchers remain unswayed by the new assessment of the skull, first unearthed in 1990. The weight of evidence from genetic analysis and other fossils, they say, suggests a much more recent origin for our species, Homo sapien.

“I am afraid that I remain unconvinced by the dates suggested,” said Marta Mirazón Lahr, a Cambridge archaeology professor who was not involved in the study.

The cranium in question is one of several dug up at an archaeological site along the banks of the Han River, a tributary of the Yangtze, in central China. Other research has dated the site at about 1 million years old.

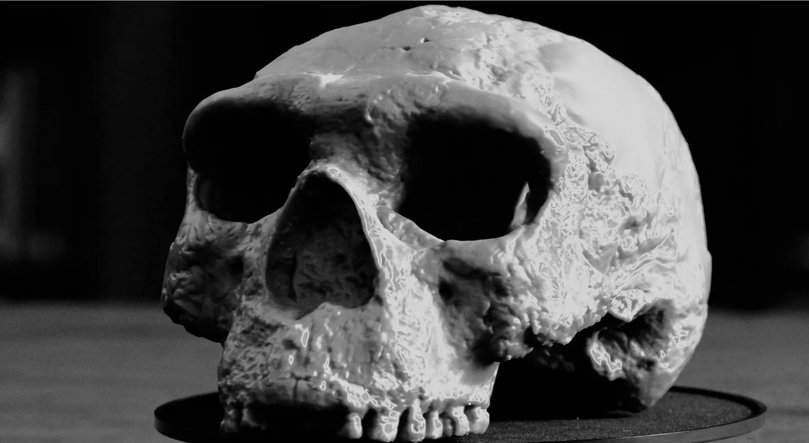

Scientists were keen to examine the skulls and place them on the tree of human evolution. But the first of the skulls, found in 1989, was badly crushed by sediment, as if a steamroller had smushed it from the eyebrow to the back of the head. The second, discovered the following year and dubbed “Yunxian 2,” wasn’t in much better shape.

For a while, paleontologists speculated that the skulls belonged to one of the earliest lineages on the tree of human evolution, Homo erectus. But when paleoanthropologist Xijun Ni got his hands on Yunxian 2 several years ago, he assessed that it was too large for that.

“When I had a chance for the first time to hold the specimen, I suddenly realised it’s so big,” said Ni, a Chinese Academy of Sciences researcher who co-wrote the study.

With skull in hand, Ni, Stringer and their colleagues painstakingly put its shattered pieces back together like a jigsaw puzzle — at least digitally, after giving the fossil a CT scan and reconstructing the cranium in a computer program. To fill in missing pieces, the researchers incorporated some anatomical elements from the first skull, called Yunxian 1.

“There were so many cracks and broken pieces,” Ni said. “It’s very much like a digital surgery.”

Eric Delson, a paleoanthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York who was not involved in the study, called the reconstruction of the skull “fantastic,” especially when “compared to the squashed pancake it was before”.

“This paper is a really important contribution,” said Suzy White, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Reading in Britain not involved in the study. “This fossil has been difficult to interpret due to its distorted appearance.”

The digitally restored skull revealed a mix of primitive and modern traits. The skull is low and long, like the oldest members of the Homo genus, but the brain it contained must have been big, like in modern humans. The researchers concluded that it belonged to a group of early humans dubbed the longi clade, which likely includes a group called the Denisovans.

Given the understanding that the site where the skulls were unearthed is about 1 million years old, the team used that date as a reference point to refashion the tree of life describing human evolution. They concluded that the longi clade branched from the lineage of modern humans about 1.32 million years ago while Neanderthals diverged 1.38 million years ago.

But Lahr, the Cambridge scientist, said the best genomic evidence suggests that Neanderthals and Denisovans are actually more closely related to one another than they are to modern humans, in conflict with how the newly proposed tree branches.

And the consensus view from geneticists is that our species is a relative newcomer, branching off only 500 to 700 thousand years ago. Neanderthals and Denisovans are so closely related to modern humans that the three groups once interbred with each other.

Svante Pääbo, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who won a Nobel Prize for discovering sexual intermingling between ancient human species, said only the retrieval of DNA, or perhaps proteins, will resolve the skull’s relationship with the rest of humanity.

Pääbo added that there is not “enough information from the morphology of these specimens to confidently determine how they are related to each other, much less date the divergences between them.”

Stringer and Ni said the skull is too old to retain DNA. And they acknowledged that, without more fossils, it is impossible to know if their reconstruction is perfect. They hope a third skull, found in 2022 at the same site, can shed more light.

“Some researchers may be skeptical of these relatively deep divergence dates,” Stringer said. “But if Yunxian is indeed an early member of the longi-Denisovan clade, this necessarily pushes back the minimum age of that clade to at least 1 million years.”