The sun is at its solar maximum — which means more auroras are likely in store

The sun's recent solar flares have triggered severe geomagnetic storms and supercharged dazzling displays of the northern lights.

The sun is awake.

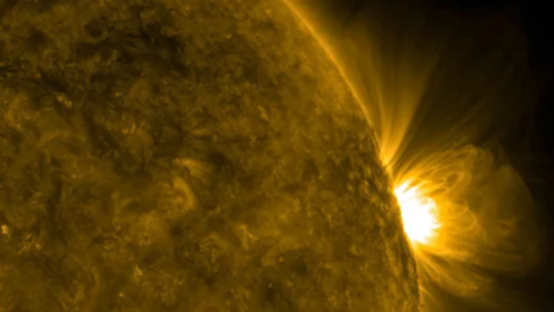

In recent months, Earth’s star has ramped up activity, with giant flares erupting off the surface and belching streams of plasma and charged particles into space.

Several of the solar storms have been aimed at our planet, and they triggered severe geomagnetic storms and supercharged dazzling displays of the northern lights.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The sun’s flurry of outbursts, coming after years of relative quiet and calm, is a sure sign that the star has entered a busy phase of its natural cycle, according to experts: solar maximum.

The active period is likely to continue over the next year, which means more solar storms and spectacular auroras could be in store.

“This is definitely the season for big solar storms,” said Kelly Korreck, a program scientist in the heliophysics division at NASA. “I expect we will see the skies lit up with auroras again.”

Later this month, NASA will get an up-close view of the high solar activity as the agency’s Parker Solar Probe makes its closest-ever approach to the sun on December 24.

The spacecraft is on a path to swoop within 3.86 million miles of the solar surface — closer than any other human-made object in history. It is expected to fly through plumes of the sun’s plasma and potentially dive into active regions of the star.

“If you think of an American football field, and Earth is on one side and the sun is on the other, this is like going to the sun’s four-yard line,” Korreck said.

The Parker Solar Probe was launched in 2018 on a mission to study the sun’s atmosphere, an ultrahot region known as the corona.

Last month, the car-size spacecraft flew by Venus in a maneuver that will help slingshot it near the sun.

Korreck said the probe’s close encounter could yield especially valuable insights if there are active sunspot regions — temporary features that appear as dark blemishes on the sun’s surface — along its path. Such observations could help researchers better understand how the sun’s activity waxes and wanes.

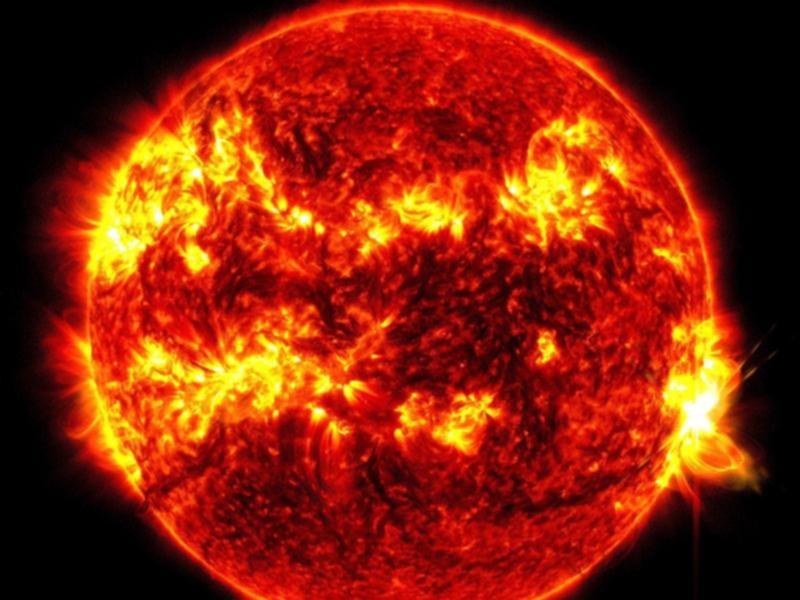

The solar cycle generally lasts around 11 years, as the sun transitions from periods of low to high magnetic activity.

As the star moves out of its calm phase — solar minimum — and reaches the height of the solar cycle, its magnetic poles flip, ushering in solar maximum, when activity is heightened and eruptions become more frequent and intense.

The main way scientists can tell that the sun has reached its maximum is by monitoring sunspot formation.

As the sun spins, its magnetic field becomes roiled, warping and tightening in some areas, Korreck said. That’s what creates the sunspots that appear in telescope images as dark patches.

“The sun is a magnetic ball, but because it doesn’t move as a solid object, its magnetic field gets all twisted up as it turns,” Korreck said.

The number of those sunspots steadily increases as the star moves toward solar maximum. Once there is a notable decline, researchers can define the start and end of the active period.

In some sunspot areas, the magnetic field can be about 2500 times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field, according to NASA.

Over time, sunspots can release enormous amounts of pent-up magnetic energy in the form of solar storms.

Two major solar storms this year — one in May and another in early October — stunned skywatchers as far south as Texas and Alabama with night skies painted in bright pink, green and purple hues.

The event in May was the strongest geomagnetic storm to hit Earth in two decades, according to NASA.

Auroras occur when clouds of charged particles that spew from the sun during solar storms slam into Earth’s magnetic field and interact with atoms and molecules in the planet’s upper atmosphere.

The colourful displays are a beautiful byproduct of that process, typically visible only at high latitudes. But during periods of intense solar activity, the lights can wander much farther south than usual.

But there can be negative consequences, as well. Strong geomagnetic storms can cause problems for astronauts in space, along with GPS systems and satellites in orbit.

Solar particle party

During a coronal mass ejection, the sun expels billions of tons of material, some of which travels toward our planet. The Earth’s magnetic field deflects most of the sun’s particles, but some enter at the poles, where interactions with our atmosphere create the aurora borealis.

Eruptions from the sun also have the power to disrupt communications and power grids on Earth because the atmosphere is being bombarded with charged particles, Korreck said.

Both NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration monitor the sun’s activity, but Korreck said space weather forecasts are still in their infancy.

“We are where terrestrial weather forecasts were 30 years ago,” she said.

“We can’t really predict out the long term very well.”

That’s partly why scientists are eager to study the sun’s maximum phase.

A better understanding of the solar cycle will help researchers understand the potential consequences for humans on Earth — and perhaps one day for anyone on the moon or Mars, Korreck said.

“Eleven years from now, at the next solar maximum, there should be folks on the moon,” she said.

“That’s pretty striking. And it will be so interesting to see how things have changed from the last solar cycle to the next and the next and beyond.”

Originally published on NBC/7NEWS