THE NEW YORK TIMES: AI video generators are now so good you can no longer trust your eyes

THE NEW YORK TIMES: The tech could represent the end of visual fact — the idea that video could serve as an objective record of reality.

This month, OpenAI, the maker of the popular ChatGPT chatbot, graced the internet with a technology that most of us probably weren’t ready for.

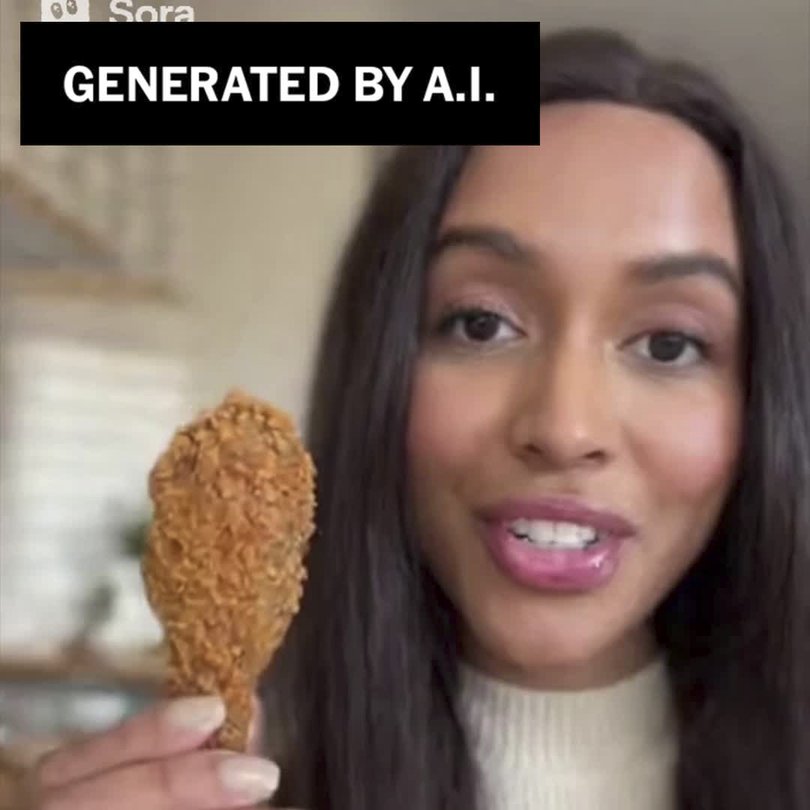

The company released an app called Sora, which lets users instantly generate realistic-looking videos with artificial intelligence by typing a simple description, such as “police bodycam footage of a dog being arrested for stealing rib-eye at Costco.”

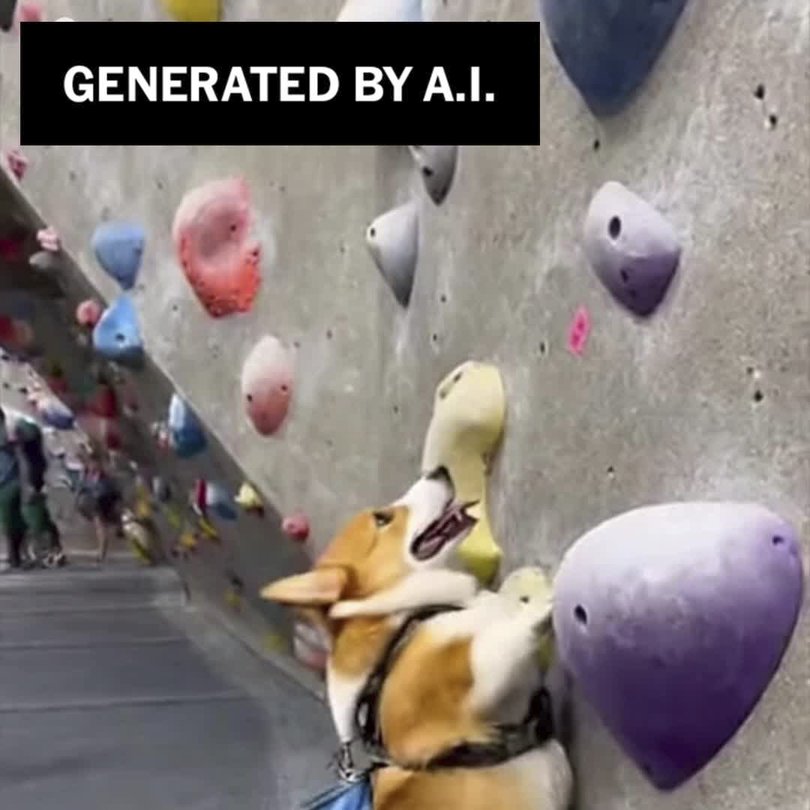

Sora, a free app on iPhones, has been as entertaining as it is has been disturbing. Since its release, lots of early adopters have posted videos for fun, like phony cellphone footage of a raccoon on an airplane or fights between Hollywood celebrities in the style of Japanese anime. (I, for one, enjoyed fabricating videos of a cat floating to heaven and a dog climbing rocks at a bouldering gym.)

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Yet others have used the tool for more nefarious purposes, like spreading disinformation, including fake security footage of crimes that never happened.

The arrival of Sora, along with similar AI-powered video generators released by Meta and Google this year, has major implications. The tech could represent the end of visual fact — the idea that video could serve as an objective record of reality — as we know it. Society as a whole will have to treat videos with as much scepticism as people already do words.

In the past, consumers had more confidence that pictures were real (“Pics or it didn’t happen!”), and when images became easy to fake, video, which required much more skill to manipulate, became a standard tool for proving legitimacy. Now that’s out the door.

“Our brains are powerfully wired to believe what we see, but we can and must learn to pause and think now about whether a video, and really any media, is something that happened in the real world,” said Ren Ng, a computer science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who teaches courses on computational photography.

Sora, which became the most downloaded free app in Apple’s App Store this week, has caused upheaval in Hollywood, with studios expressing concern that videos generated with Sora have already infringed on copyrights of various films, shows and characters.

Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, said in a statement that the company was collecting feedback and would soon give copyright holders control over generation of characters and a path to making money from the service.

(The New York Times has sued OpenAI and its partner, Microsoft, claiming copyright infringement of news content related to AI systems. The two companies have denied those claims.)

So how does Sora work, and what does this all mean for you, the consumer? Here’s what to know.

Q: How do people use Sora?

A: While anyone can download the Sora app for free, the service is currently invitation-only, meaning people can use the video generator only by receiving an invite code from another Sora user. Plenty of people have been sharing codes on sites and apps like Reddit and Discord.

Once users register, the app looks similar to short-form video apps like TikTok and Instagram’s Reels. Users can create a video by typing a prompt, such as “a fight between Biggie and Tupac in the style of the anime ‘Demon Slayer.’” (Before Altman announced that OpenAI would give copyright holders more control over how their intellectual property was used on the service, OpenAI initially required them to opt out of having their likeness and brands used on the service, so deceased people became easy targets for experimentation.)

Users can also upload a real photo and generate a video with it. After the video generates in about a minute, they can post it to a feed inside the app, or they can download the video and share it with friends or post it on other apps such as TikTok and Instagram.

When Sora arrived this month, it stood out because videos generated with the service looked much more real than those made with similar services including Veo 3 from Google, a tool built into the Gemini chatbot, and Vibe, which is part of the Meta AI app.

Q: What does this mean for me?

A: The upshot is that any video you see on an app that involves scrolling through short videos, such as TikTok, Instagram’s Reels, YouTube Shorts and Snapchat, now has a high likelihood of being fake.

Sora signifies an inflection point in the era of AI fakery. Consumers can expect copycats to emerge in the coming months, including from bad actors offering AI video generators that can be used with no restrictions.

“Nobody will be willing to accept videos as proof of anything anymore,” said Lucas Hansen, a founder of CivAI, a nonprofit that educates people about AI’s abilities.

Q: What problems should I look out for?

A: OpenAI has restrictions in place to prevent people from abusing Sora by generating videos with sexual imagery, malicious health advice and terrorist propaganda.

However, after an hour of testing the service, I generated some videos that could be concerning:

— Fake dashcam footage that can be used for insurance fraud: I asked Sora to generate dashcam video of a Toyota Prius being hit by a large truck. After the video was generated, I was even able to change the license plate number.

— Videos with questionable health claims: Sora made a video of a woman citing nonexistent studies about deep-fried chicken being good for your health. That was not malicious, but bogus nonetheless.

— Videos defaming others: Sora generated a fake broadcast news story making disparaging comments about a person I know.

Since Sora’s release, I have also seen plenty of problematic AI-generated videos while scrolling through TikTok. There was one featuring phony dashcam footage of a Tesla falling off a car carrier onto a freeway, another with a fake broadcast news story about a fictional serial killer and a fabricated cellphone video of a man being escorted out of a buffet for eating too much.

An OpenAI spokesperson said the company had released Sora as its own app to give people a dedicated space to enjoy AI-generated videos and recognize that the clips were made with AI. The company also integrated technology to make videos simple to trace back to Sora, including watermarks and data stored inside the video files that act as signatures, he said.

“Our usage policies prohibit misleading others through impersonation, scams or fraud, and we take action when we detect misuse,” the company said.

Q: How do I know what’s fake?

A: Even though videos generated with Sora include a watermark of the app’s branding, some users have already realized they can crop out the watermark. Clips made with Sora also tend to be short — up to 10 seconds long.

Any video resembling the quality of a Hollywood production could be fake, because AI models have largely been trained with footage from TV shows and movies posted on the web, Hansen said.

In my tests, videos generated with Sora occasionally produced obvious mistakes, including misspellings of restaurant names and speech that was out of sync with people’s mouths.

But any advice on how to spot an AI-generated video is destined to be short-lived because the technology is rapidly improving, said Hany Farid, a professor of computer science at the University of California, Berkeley, and a founder of GetReal Security, a company that verifies the authenticity of digital content.

“Social media is a complete dumpster,” said Farid, adding that one of the surest ways to avoid fake videos is to stop using apps like TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times