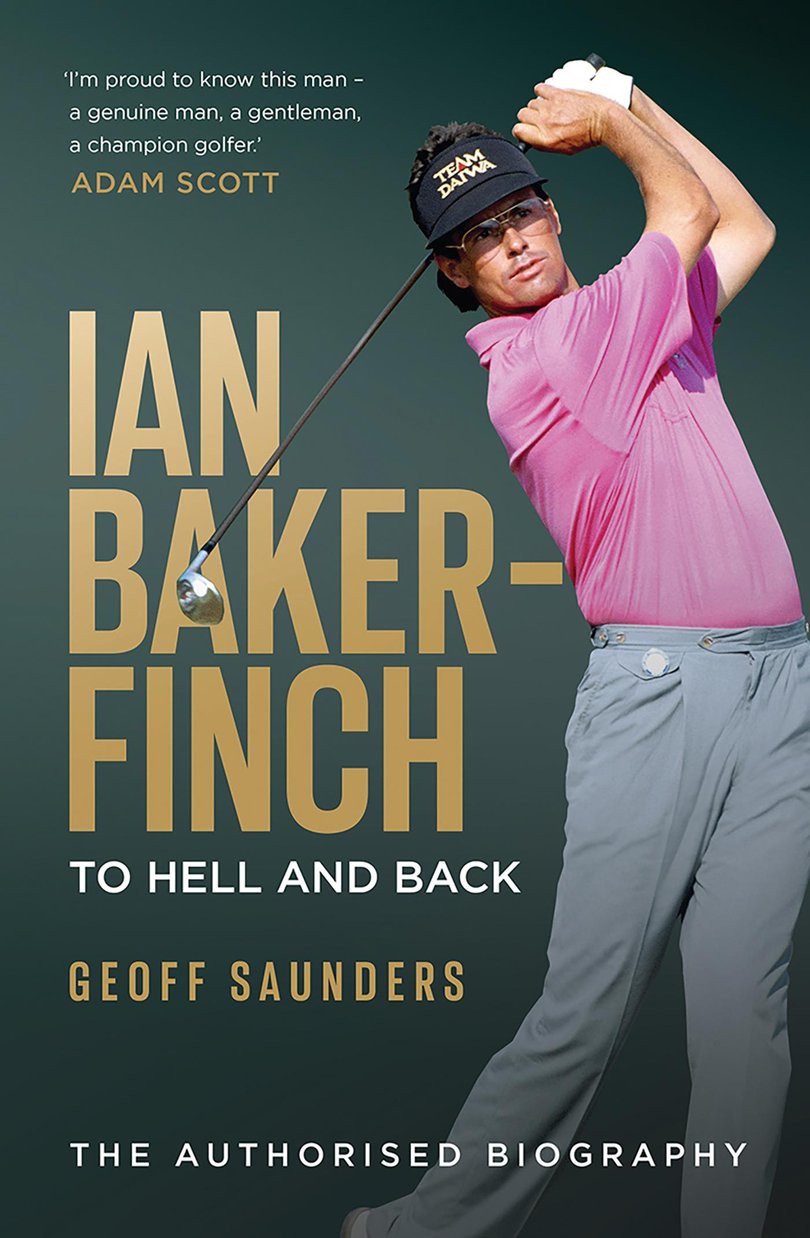

Ian Baker-Finch’s biography finally explores what led to his stunning fall from the top of the golfing world

The 1994 Masters provided Ian with one ray of hope in a dark season.

In fourth place after three identical scores of 71, Ian fell away with two balls in the water in his final round of 74, dropping down into a tie for tenth. Spain’s Jose Maria Olazabal won by two shots, continuing the inspired scrambling tradition of his countryman Ballesteros. The Masters that year was notable for being the first time since 1954 neither Nicklaus nor Palmer made the cut. Their long era was over, but so was Ian’s tragically short career in the majors. He would never make a cut in any major again and was losing his game with alarming speed.

He played poorly at Hilton Head the week after the Masters, and it only got worse from there; he missed the next ten cuts in a row as a worrying pattern developed for Jennie and the children. The family was living in Orlando and their plan was for the two girls to attend school during the week, then for Jennie to join Ian at the weekend. ‘It became dispiriting for all of us, as I was always home by Friday night after missing every single cut.’

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Ian’s loss of form became equally tough on Jennie and the girls. Jennie says, ‘I would just leave Ian alone and avoid asking, “How do you feel?” He would disappear into his room and was obviously upset with himself. Two or three hours later we could talk about it, but I wouldn’t try to make him feel better – that didn’t work. Ian tried extremely hard not to bring it home but became a little depressed. One thing about having little children was they did not really know about the issues. All they cared about was the fact their dad was home. He was with a beautiful family which helped put it into perspective.’

A cruel joke circulated among the caddies: ‘Whose is the best bag to have on tour?’

Answer: ‘Finchy’s because you get every weekend off.’

It looked briefly as if Ian was emerging from his slump in August at the World Series in Ohio, when he shot 67 in the first round to sit just two shots behind the leader. But his second round was the stuff of golfing nightmares. ‘That year the World Series was played on Firestone’s North Course – they were rebuilding the greens on the South Course. There was water on every hole of the North Course, and what I feared most on some of the holes – a combination of both out of bounds and water. If it was there, that is where I hit it.

‘I shot eighty-two, which included ten penalty shots and twenty-one putts. The rest of my game, apart from my driving, was fairly good. With three holes left to play, I only had one ball left in my bag. The 16th had water, the 17th was a long par three over water, and the 18th also brought water into play. I survived the first two of the final three holes with what I thought was my last ball. On the 18th, I hit my drive over the water and thought I was going to be fine, then I shanked my second shot into the water.

A cruel joke circulated among the caddies: ‘Whose is the best bag to have on tour?’ Answer: ‘Finchy’s because you get every weekend off.’

‘Walking down the last hole I said to my caddie, Pete, “Hey, mate, we must be out of balls.” Luckily, Pete had saved one used ball we had rotated out on one of the par threes – we never used a new ball on a par three in those days. So, I used this final recycled ball, making a bogey five on the last hole and was able to at least finish the round – with eighty-two.’

Ian’s crash had become so dramatic he was starting to receive a torrent of unwanted advice from the public. ‘During this time, I had 4000 letters. I had so many flaming rocks sent to me and suggestions like, “Come with me to the mud baths in southern Italy and you are sure to be cured.”’

A letter to Ian from Carol in New South Wales was typical.

Dear Mr Ian Baker-Finch,

Sleep with this Indian stone under your pillow. It resonates with your spirit. You have given away your own power. You have forgotten the beauty of your own soul.

Carol

Looking back on this traumatic period in their lives, Jennie says, ‘The unsolicited advice overwhelmed Ian. Sending a rock to him? Ridiculous. These days he would have one person to listen to, but he never really had a coach and he had learned golf from a book. Even when he was feeling like crap, if someone approached him, Ian would be nice and friendly while a total stranger tried to give him advice. He would just sit there and nod when anyone else would have said, “Off you go.” Ian was far too nice. A lot of people told him he needed to be more like a Greg Norman or a Nick Faldo but that was not his personality, and he was never going to change.’

WIFE’S ANGUISH

Ian shot 66 in the pro-am at the Hyundai Masters in Korea for a new course record, then an 81 when the tournament proper began. By this time, he was practising far too hard, hitting at least 100 drives a day, every day. His body was not enjoying the workload. ‘I have never blamed my loss of form on injury, but possibly it contributed to my decline. I was starting to develop serious issues with both my shoulders.’

By 1995, the state of Ian’s game was dire. He played in 15 straight tournaments on the US Tour, missing every single cut. He was shooting 80, or worse, in every fourth round he played and was averaging a near-fatal four penalty shots per round. It was not getting any better.

Jennie found it heartbreaking to watch her husband’s torment at close quarters. ‘He felt he had to do something about his game but just could not work out why it was happening. It just got worse and worse with the pressure of competition, not knowing why he was hitting those bad drives. It wasn’t all the time, but it was enough to make him miss cuts. The girls were a little older, and they became sorry when he came home early. They knew the reason was he hadn’t played well.’

Family life continued as best it could under huge strain. Jennie recalls, ‘I used to call him Mr Disney and I was the Gestapo. If he hadn’t seen Hayley and Laura for ages, he tried to make sure he was the fun parent. Ian tried never to be away for more than two weeks.’

The elder statesmen of the game, Nicklaus and Palmer, were sympathetic to Ian. He had played with Nicklaus in the US Open in the process of another missed cut. Nicklaus kindly offered Ian the opportunity to stay with him for a week or two to try to sort out his problems. Ian did not take advantage of the invitation.

Then, at the 1995 Open Championship, Ian was drawn with Palmer for the first two rounds at St Andrews. It was Palmer’s last Open and huge galleries followed them on the first two days. Ian’s opening tee shot, hit out of bounds left, has been unkindly described by media as ‘the worst tee shot ever seen at the Open’ because players have a double fairway – the 1st and 18th – to aim for. Ian avoids recrimination and blame when looking back, but he bristles at the portrayal of his infamous tee shot, feeling it should be put into proper context. ‘Commentators and spectators say the 1st fairway on the Old Course is one hundred and sixteen yards wide from one side to the other – but it is not. During the Open, the stands encroach on the right-hand side of the fairway by about fifty yards.

‘The best play is to the left with the drive, aimed at the Swilcan Bridge, to give you a better angle into the green. The day of that tee shot with Arnie, we had a thirty-mile-per-hour wind into us. My hat came off on the downswing and I hit a hook out of the toe, which landed on Grannie Clark’s Wynd [the road running across both fairways]. The ball shot left and under the fence – out of bounds. People have harassed me since the day I hit that drive, but it was not really that bad, and was barely a twenty-five-yard hook.’ In the inaugural four-hole event for past champions in 2000, four previous champions, including Bill Rogers, hit their drives out of bounds down the left side of the same shared fairway.

People have harassed me since the day I hit that drive, but it was not really that bad, and was barely a twenty-five-yard hook.

By 1996 Ian’s playing days were swiftly coming to an end. ‘It had become impossible for me to keep playing, particularly with the press continually crowding in on me. It was so very embarrassing. It was like, “Finch is coming and he’s going to miss another cut. Let’s go and watch him and harass him.” After the first two rounds of the British Open at Lytham in 1996 I had scored 78-81 and was surrounded by the media. It was like they had put me on some form of death watch. So, I said to them, “I have finished. I am done. I am going home to Australia, to rest and try and figure this out.” But ultimately I could not figure it out.’

Jennie was frustrated and felt helpless. ‘I would say “It’s okay” when I knew it really wasn’t okay.’

The late Bruce Edwards, Tom Watson’s caddie, caddied for Ian during the Open in 1996 and Ian recalls, ‘Apart from the penalty shots I incurred, Bruce could not believe how well I played from all the impossible places I managed to hit it into – including several drives out of bounds. I could still chip and putt with the best in the world, but I had totally lost confidence in my long game.’

At this point Ian had not entirely given up. He went through a period near the end of his playing career when he was trying almost every available top-level coach. ‘It started in 1996 when I had played so badly in the US Open. Butch Harmon came up to me and offered to try to help me. I was going to see him but never made it, which was probably a mistake in hindsight. He left his offer open to me, but it was a tricky situation because he was Greg Norman’s coach by then. So, I stayed away.’

By 1996 Ian and Jennie decided to quit the US Tour and move back to Australia. ‘I was not quitting golf, but I wanted to get back to Australia, take a six-month break and fix my injuries. I was still exempt on the US Tour for the rest of 1996 and for five years after that. I had played eleven events in 1996 and then the Tour banned me in 1997 as I had not played the required fifteen events. In hindsight I should have taken a major medical exemption at this stage of my career to leave my playing options open.’

Jennie remembers their painful departure. ‘We left Orlando in mid-1996 and it was sad. We left behind lots of weeks without making money and Ian wondering why this was happening to him. Each week he would go out and it was there in his mind: “Am I going to play well this week? Or am I not going to play well?” It was very tough so we went back to Australia to have his shoulder injuries treated, and his feet also needed to be repaired.’

‘Moving back to Australia. I wondered during the dark times from 1994 to 1996 whether I would be able to play well if no one knew who I was. It was a fantasy, but the media scrutiny in the States was intense, and in Australia it was unbearable. I would hit a drive into the trees and there would be six cameramen there.’

Back in Australia, Ian did not play for six months. Even if he had wanted to, his body needed time to heal. ‘I had my shoulders rehabilitated, and they taped up my feet and separated my toes. I could not wear shoes for three months.’ The years of cramming his feet into shoes far too small for him as a boy had taken their toll.

Jennie recalls, ‘When we went back to Australia, we thought it was only likely to be for a short time. I told Ian that if he wanted to stick to playing and get through the problems with his golf, I would be with him, and we would do it together. I also told him if he wanted to try something else, we would do it. In the end, I told him I could not make the decision for him. I knew he really wanted to stay as a golfer, and if he was honest with himself he probably thinks now he should have given it another go.’

I CAN’T DO THIS ANYMORE

During Ian’s time out of the game an opportunity presented itself: television commentary. He covered 12 events as lead analyst on the Australian Tour for all the networks – ABC in Australia and channels Seven, Nine and Ten – from October 1996 to the end of February 1997. He was paid A$10,000 per week during the few weeks of the season, and he recalls, ‘At least it was an income; I had nothing else coming in.’

Before 1996 Ian had tried his hand at broadcasting on weekends for ABC in the US at the 1994 and 1995 Opens, and he worked in tandem with the great BBC commentator Peter Alliss. ‘I had plenty of fun with Peter on the BBC. Peter said he loved working with me and reassured me I would be good on the microphone if ever I had to be. In 1996 Jack Graham was the producer for ESPN and ABC in the US, and he said, “We would love you to come in on the weekend at the British Open if you do not make the cut,” which I agreed to do.’

In July 1997, Ian had the option to do some commentary work on Open weekend at Royal Troon but had entered to play in the tournament (past Open winners were then exempt until they turned 65). He was in two minds as to whether or not he should play. In the week before the Open, Ian had been on a golf tour in Ireland, driving everywhere accompanied by his coach at the time, Gary Edwin, and some friends, including Kevin Cross and fellow professional Grant Dodd. ‘I had sent my caddie home and was talked into playing at Troon.’

Ian’s back was aching from all the golf and driving, but Cross was in the minority in trying to dissuade his friend from playing, pointing out, ‘You are taking ten Advil per day and would be stupid to play with your sore back.’

Ian reflects, ‘Most of the Aussie boys were saying, “Finchy, you have played every Open since 1984, why would you not play in this one?” So, I did.’

It would prove to be the worst decision he ever made.

Todd Woodbridge, an Australian tennis pro and a friend of Ian and Jennie’s, was staying in the same hotel during the Open and volunteered to caddie for Ian for the first two rounds.

Ian says, ‘It was just a nightmare. I hit every drive in the left rough. It was one of those Troon days with the wind howling at forty miles an hour and I think the average score for the field in the first round on the back nine was forty. It was a tough day. My back was hurting, and I ground it out and shot ninety-two.’ Ian signed his card and walked off the last green thinking, ‘I just can’t do this anymore.’

‘It was not that I couldn’t play,’ he says. ‘I just couldn’t play under pressure. My tee shots were the problem and I kept hitting these terrible low hooks. Once I had hit one, it was hard to stop hitting them for the rest of the day.’

Ian went into the clubhouse and collapsed in the locker room with Gary Edwin and Todd Woodbridge there in support. R&A media officer David Begg recalls, ‘Jennie faced the press with Ian, who was absolutely broken.’

Reliving the nightmare, Ian says, ‘I then stupidly faced the media and followed by working on the TV coverage in the afternoon for ABC, which was equally stupid, but I had committed to it. I finished the Thursday afternoon coverage and told ABC I was going home. They never paid me, but I was kind of glad they had not. Jack Graham said to me, “Hopefully you can sort it out and get back to playing, but if you don’t you have a job with ABC in America next year.”’

Ian reflects, ‘If I had not played that first round in the 1997 Open, I believe I may have figured it out, come back and played again. My score of ninety-two left me with so much baggage. The fear of going out and doing it again became an insurmountable barrier for me.’

Ian and Jennie had been staying in the Old Course Hotel in St Andrews and taking a helicopter to Troon each day. The night of Ian’s final round in a major, his fellow players sent beer, champagne and flowers to their room. On the scoreboard at Royal Troon the next day, ‘92 WD’ appeared beside Ian’s name.

At the age of 36, six years after he had become the Champion Golfer of the Year, Ian Baker-Finch’s playing career was over.

This is an edited extract from Ian Baker-Finch To Hell and Back by Geoff Saunders published by Hardie Grant Books. Available at all bookstores nationally