How Beirut was once known as the Paris of the Middle East before it came to a brutal end in 1975 civil war

Before it became a city synonymous with urban disasters, conflict and chaos, Beirut was a colourful, prosperous city known as the Paris of the Middle East.

Before it became a city synonymous with urban disasters, conflict and chaos, Beirut was a colourful, prosperous city known as the Paris of the Middle East.

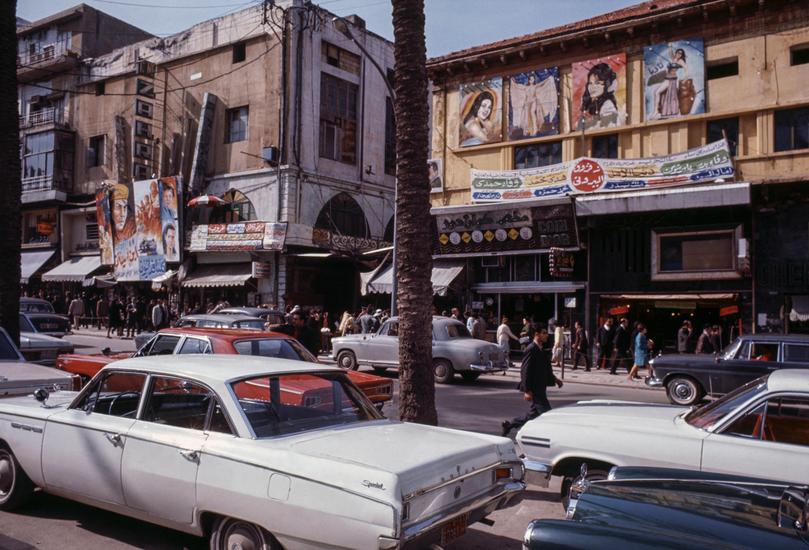

Between 1955 and 1975, in its Golden Age — after gaining independence from the French but before civil war erupted — the Lebanese capital was a cultural and financial hub for the region.

It was a cosmopolitan mecca revered for its rich culture, French architecture, world-class food, fashion, art and glamorous lifestyle offerings that lured curious tourists and high-flying celebrities, alike, to its shores.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Luxury hotels and clubs dotted throughout the city made Beirut a “jet-setter’s playground, with a social scene that rivalled its European counterparts”, Vogue wrote.

The most famous luxury hotel, the Hotel Saint-Georges, played host to Hollywood icons like Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, Marlon Brando, and French starlet Brigitte Bardot, and royals like King Hussein of Jordan, and the Shah of Iran and his wife Princess Soraya.

Hamra Street was likened to the Champs-Élysées of Beirut, lined with fashion stores, theatres, restaurants, cafes, and hotels visited by artists, poets, writers, and intellectuals.

There were more than a dozen cinemas on Hamra Street alone — including the famous Eldorado, the Picadilly, and the Versailles — cementing Beirut’s title as the cinema capital of the region.

Downtown Beirut was also a bustling hive of activity, home to traditional markets frequented by locals and fashionable boutiques and haute-couture houses. It also was home to the bars, brothels, and gambling houses.

Even Beirut Airport was new and exceptional and served as the backdrop to a number of European spy films at a time when air travel was rapidly expanding.

But those glittering 20 years came to a brutal end in 1975 when civil war broke out and tore the city, and country, apart.

Over the next 15 years, about 150,000 people would be killed — or presumed dead after being kidnapped or disappeared — and almost one million people would flee Lebanon.

Beirut would be split into hostile territories along the Green Line, the battleline that ran through the middle of the city where Christian militias (to the east) exchanged fire with Palestinian and Sunni militias (to the west).

Many of the landmarks that epitomised the Golden Age would be left scarred or destroyed by the civil war — like the Saint-Georges Hotel, which was occupied and left in ruins by warring militias during the Battle of the Hotels, and later occupied by the Syrian army until 1990.

The great, horrific irony of it all is that the French imperial influence that Beirut cultivated to become the Paris of the Middle East (Lebanon was occupied by the French military after World War I until its independence in 1943) would play a role in its downfall.

And in the decades since, whatever remnants of the gilded mid-century era would be wiped away by the rolling toll of cross-border conflict, most recently with Israel, as well as continued civil unrest, political instability and disasters like the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

Even recovery efforts have snuffed glimmers of the Beirut-that-was, with battered French-style buildings and streets cleared in favour of construction projects that have seen one Beirut writer opine: “much of the architectural memory of a city like Beirut is being erased”.