The Economist: How Ecuador became Latin America’s deadliest country

In 2019 it was one of the safest countries in Latin America, with a homicide rate of 6.7 per 100,000. Some Ecuadorean sources estimate that in 2023 the homicide rate will have grown more than six-fold.

One of Ecuador’s most-watched news programmes, El Noticiero, was broadcasting live when gunmen stormed the studio. Cameras rolled as hooded gangsters pistol-whipped staff to the floor. They then strutted on air for 15 minutes, flicking gang signs to stunned viewers and taking selfies while waving machetes, dynamite and machineguns.

This thuggery, beamed across the country on the afternoon of January 9th by a state-owned channel, tc Televisión, shocked Ecuadoreans as mayhem seized the country this week. It is the latest, most dramatic episode in its four-year-long slide into the grip of drug gangs.

In 2019 it was one of the safest countries in Latin America, with a homicide rate of 6.7 per 100,000. Some Ecuadorean sources estimate that in 2023 the homicide rate will have grown more than six-fold, to 45 per 100,000, making their country the deadliest in mainland Latin America.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.

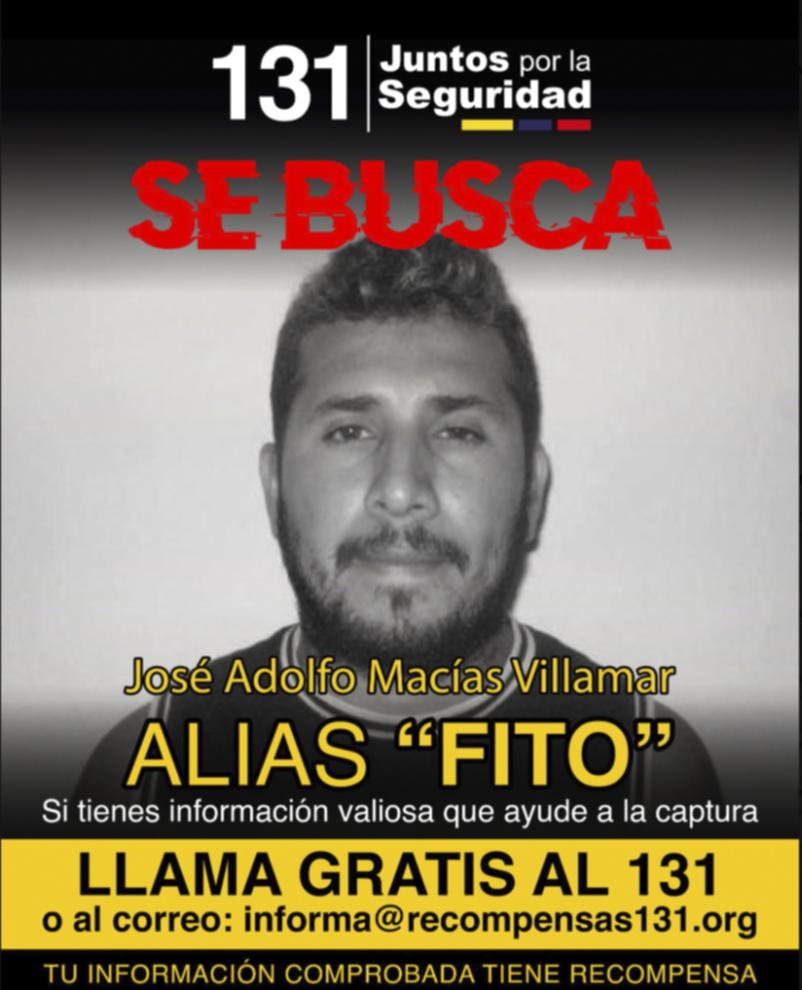

The events were set in motion on January 7th, when guards at La Regional prison in Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city, discovered that Adolfo Macías, boss of the drug gang Los Choneros, was not in his cell. He had been serving a 34-year sentence for murder and drug-trafficking. Gang members in prisons across the country began rioting as news of his escape spread. Videos circulated on social media, showing gangsters taking prison guards hostage and shooting them. Some were hanged.

The next day Daniel Noboa, Ecuador’s president, declared a state of emergency and imposed a nightly curfew. He sent the army in to take control of the prisons. Gangsters fought back on the streets of cities across the country, detonating bombs, burning cars and kidnapping policemen. On January 9th another armed group raided Guayaquil University, taking students hostage and exchanging fire with the police. Mr Noboa then declared an “internal armed conflict” and ordered the army to “neutralise” some 22 organised crime groups, including Los Choneros. As The Economist went to press, armoured cars and soldiers roamed Ecuador’s streets. The gunmen who stormed the TV station had been arrested, but at least ten people had already been killed.

This violence first took root in Colombia. Ecuador, particularly its port at Guayaquil, became a more important hub for the shipment of cocaine from Peru and Colombia after Colombian ports tightened their security in 2009. Trade had previously been monopolised by the farc, a powerful Colombian guerrilla group, which kept violence to a minimum. But after the farc signed a peace deal in 2016, most of its members were demobilised. Local, regional and international gangs poured in to fill the vacuum. Mexican cartels have funded Ecuadorean ones. The Albanian mafia has also expanded its presence in Ecuador. Such a rapid influx of international organised crime was facilitated by Ecuador’s dollarised economy and by lax visa requirements for foreigners.

Small-time Ecuadorean gangsters like Mr Macías have become kingpins. Los Choneros and other local gangs are thought to have armed themselves with weapons bartered by their Mexican patrons for cocaine shipments. They now possess machineguns, rifles and grenades that enable them to face off against Ecuador’s poorly trained armed forces.

Ecuadorean gangs have generated cashflow by establishing a lucrative foothold in Europe, where cocaine consumption is growing. The busiest cocaine-trafficking route in the world today runs from Guayaquil to the port of Antwerp in Belgium, according to Chris Dalby of World of Crime, an investigative outfit based in the Netherlands. Much of this cocaine is packed into shipping containers containing bananas, one of Ecuador’s biggest exports. Europe’s demand “has turned Ecuadorean ports into one of the most valuable pieces of infrastructure you can control, if you are a drug-trafficking group in Latin America,” says Will Freeman of the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

That cash lets gangs buy off prison guards. Mr Macías and other gang leaders have turned perhaps a quarter of Ecuador’s 36 prisons into their headquarters, from which they organise attacks and recruit new members. Mr Macías escaped just before he was due to be transferred to a more secure unit in the prison complex. He must have been tipped off by corrupt officials.

Corruption of that sort is rife. In 2023 police began investigating several government officials for links with the Albanian mafia. Months later the top suspect was found dead. In 2022 25 air-force officials were punished for sabotaging radar equipment that was monitoring the activity of drug gangs in Ecuadorean air space.

Stand and deliver

Anyone who stands up to the drug gangs and their corrupt networks is at risk. Last August Fernando Villavicencio, a presidential candidate and former investigative journalist, was assassinated 11 days before the election after he threatened to take down the gangs. On January 5th Fabricio Colón Pico, a leader of Los Lobos, a rival gang to Los Choneros, was arrested allegedly for plotting to assassinate Diana Salazar, Ecuador’s attorney-general. She had been investigating links between drug traffickers and civil servants. In December she ordered the arrest of 31 people, including judges, prosecutors and policemen. Mr Colón Pico managed to escape from jail just four days after his arrest.

After campaigning on less controversial issues, Mr Noboa, who took office in November, has taken an iron fist to the gangs. He has announced that two new maximum-security prisons will be built; declared gangs to be terrorist organisations; and warned that officials who collaborate with them will be brought to justice. Like his predecessor, he is sending the army onto the streets and into the prisons. And he has called for a referendum in the coming weeks that would legalise extradition, allow police officers and soldiers to be pardoned, and enable the assets of suspected criminals to be seized.

Some of these tactics appear to copy the tactics of Nayib Bukele, the president of El Salvador, who has put some 2% of the adult population behind bars and become one of Latin America’s most popular presidents. Yet the challenges faced by the two leaders are different. The Ecuadorean gangs are far more sophisticated than those in El Salvador, and Mr Noboa, who must seek re-election in 18 months, is far weaker than Mr Bukele. Despite Mr Bukele’s success so far, the strongman approach to Latin American drug gangs has usually failed.

Mr Noboa must make a cleverer plan. He should urge his officials to share data with counterparts elsewhere in the region, which does not happen at the moment, says Mr Dalby. He should set up a register of guns, rebuild the country’s feeble anti-narcotics units and strengthen co-operation with the United States, which has offered to help. And he must bolster the state’s presence along the border with Colombia and in Guayaquil. Without all this, going to war with Ecuador’s newly empowered gangs is likely to prove futile.