The New York Times: How the Windsor women became human shields

The Windsor women have historically served as a combination of brood mares and mannequins, until something threatens the reputation of a male Windsor. Then the women have another essential role: human shield.

Once upon a time, a handsome young prince surveyed all the lovely, intelligent, kind-hearted ladies of the land and, from their number, picked his bride.

The new addition to the family was a delight, a beauty, a breath of fresh air. She enjoyed a brief honeymoon period when everyone adored her. Then something changed. Maybe she dared to express a desire or let slip an opinion. Perhaps she appeared in public looking less than perfect, or broke with tradition and refused to appear at all — or maybe it was simply a matter of what goes up must come down.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Whatever the reason, the golden girl was swiftly recast as a gold digger. Or as crass and trashy or cruel and manipulative, or ugly, or fat. She was pitted against the other women in her circle and her generation.

Princes might occasionally be turned into frogs, but princesses always seem to end up as villains or scapegoats and used to deflect heat or criticism should her husband require it.

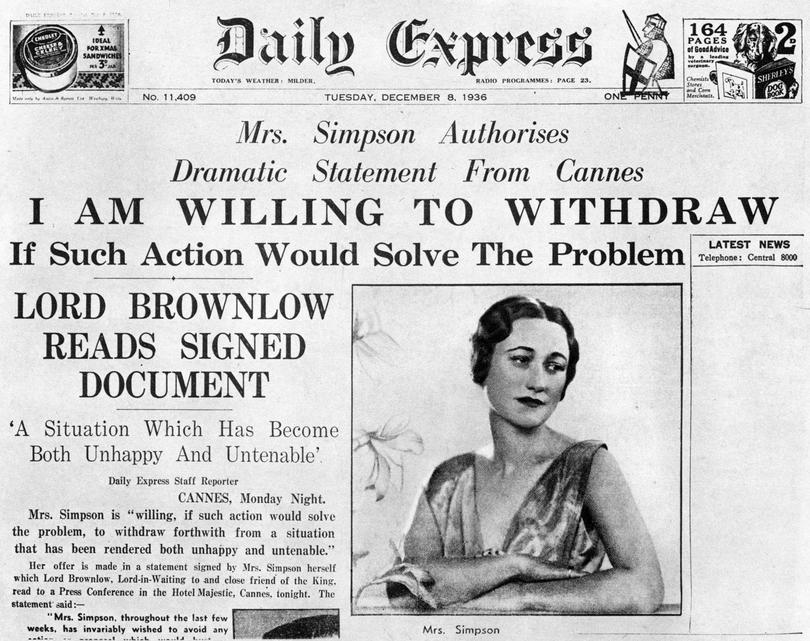

It happened to Diana Spencer, to Sarah Ferguson, to Camilla Parker Bowles, before she was Queen Camilla. It happened to Meghan Markle, whose trials were worsened by racism. In its own way, it happened to Wallis Simpson. It happened to Kate Middleton — when she and Prince William were dating, but not yet engaged, she was portrayed as a wily social climber and called “Waity Katie.” After they married, it looked as if Catherine might become the rule-proving exception, the single privileged Windsor wife allowed to float above the fray.

Perhaps everyone should have been paying closer attention to Prince Andrew’s friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, instead of his wife’s weight.

But now, Catherine, Princess of Wales, has taken her place where every royal, and royal-adjacent woman ends up: in the hot seat. With all fingers pointing at her.

As you’ll know unless you’ve been under a rock with your hands over your eyes, the palace recently released a photograph of Catherine smiling with her three adorable children — one of the first glimpses the public had had of her since before January, when it was announced that she was recovering from planned abdominal surgery and would not be taking up her public duties again until after Easter.

It took the internet about a minute to see that the photo had been retouched, and we were asked to believe that Catherine alone was responsible for photoshopping the photo (badly). The royal watcher Daniela Elser branded her a “chaos-bringer” and a “global figure of humiliation and mockery.” The “royal say-so,” she wrote, “will now be doubted for years to come.” (This, we’re to understand, is solely because Catherine photoshopped a photograph of her children for Instagram. The palace’s record on communications was of course, unimpeachable.)

Why do Windsor women so consistently come in for this kind of treatment? Start with the fact that the royals don’t actually rule Britannia, or anything else. Think of them as a family business that doesn’t make anything except babies and the case for British taxpayers to keep them around. Royals and their spouses have to prove, daily, that the monarchy is giving taxpayers value for their money; that kings and queens and lords and ladies are useful symbols, avatars of the nation’s character; that they are honest, steadfast and true.

In this system, the monarch is the most important. Male relatives are heirs or spares. The women have historically served as a combination of brood mares and mannequins. Their job is to stay thin, say little, look good in clothes, and produce heirs who will stay thin, say little and look good in clothes. (Prince Philip was said to have approved of Diana’s entry into the family because she would “breed in some height.”)

When something threatens the reputation of a more senior, male Windsor, the women have another essential role: human shield.

Has King Edward VIII abdicated and run off to France to be with Wallis Simpson? Let’s be sure to blame the American divorcée.

Has Prince Charles taken a mistress? Blame his mum for not letting her son marry his true love; blame his wife for not keeping him faithful — oh, and call the mistress ugly.

Has Prince Harry declined to perform his family duties and decamped for sunny California? Let’s blame his “narcissistic” wife for ensorcelling him!

And perhaps everyone should have been paying closer attention to Prince Andrew’s friendship with Jeffrey Epstein, instead of his wife’s weight.

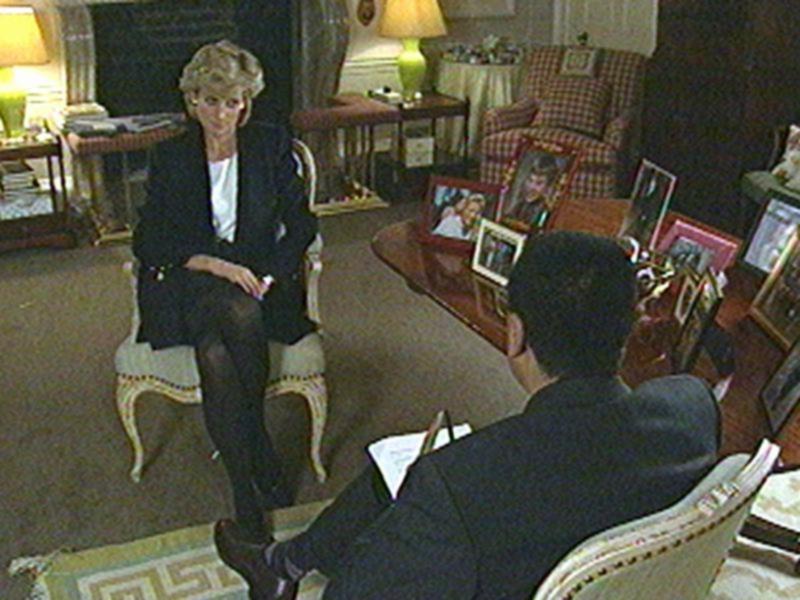

While Meghan and Harry, like Diana before them, are now free to give interviews and authorise books, Catherine cannot defend herself. Instead, she’s stuck quietly enduring her own annus horribilis.

Her reticence about her health, her apparent unwillingness to share details of her ailment or pictures of her recovery, has been contrasted — unfavourably — with King Charles III’s candour about his cancer.

When she tried to give the people what they wanted — proof of life, by way of a polished image of happy family — and it backfired, that, too, was useful. Maybe her mea culpa was meant to make us see William as trustworthy and statesmanlike by comparison; a loyal husband, steadfastly caring for the kids while the princess plays with photoshop, and not — as readers of Harry’s memoirs might be forgiven for picturing — a brother-shoving, necklace-ripping, dangerous-to-dog-bowls hothead.

While internet sleuths pore over the latest grainy images in the British tabloids, which appear to show the prince and princess out and about at a farm shop, Catherine has maintained the silence that’s practically part of the job description.

As the fairy tales (Grimm, not Disney) tell us, nothing is ever free. The bill always comes due. And, for the not-so-merry wives of Windsor, the price has always been too high.

The rule is never complain, never explain, and — if it gets to be too much — never get help. Diana, suffering from bulimia, said that the family dismissed her as “unstable.” Meghan has said she wanted to get professional help, but “I was told that I couldn’t, that it wouldn’t be good for the institution.” Royal women are expected to suck it up and live, with borrowed jewels on their fingers and a target on their backs.

Maybe there’s a happy ending to this royal mess. Maybe recent events will puncture, once and for all, the myth of Prince Charming and the happily-ever-after he’ll bring. Maybe 10 years from now a generation of teenage girls will not be humming “Someday, My Prince Will Come” and dreaming of Prince George sweeping them off their feet. Maybe we won’t ask another Diana, Meghan or Catherine to trade her voice and her agency for a nice wardrobe, a televised wedding and a lifetime of ribbon-cutting and silent smiling.

As the fairy tales (Grimm, not Disney) tell us, nothing is ever free. The bill always comes due. And, for the not-so-merry wives of Windsor, the price has always been too high.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times