THE NEW YORK TIMES: Silicon Valley has China envy, and that reveals a lot about America

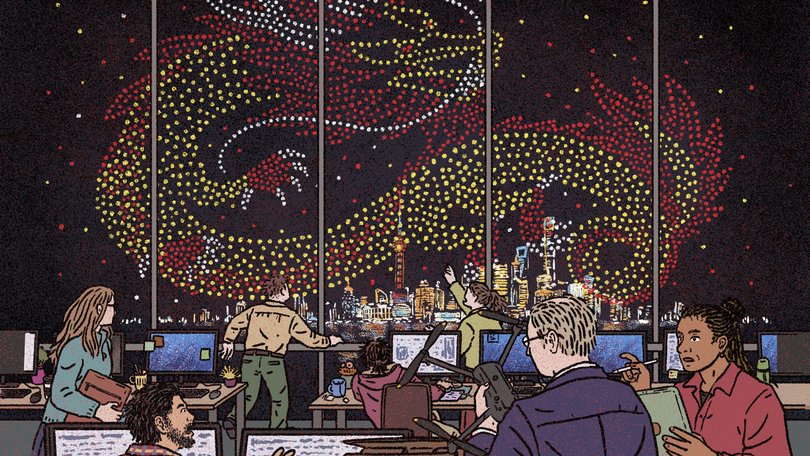

Silicon Valley has a China envy problem.

In social media posts, podcasts, interviews and newsletters, the elites of the American tech sector are marvelling at China’s speed in building infrastructure, its manufacturing might and the ingenuity of the artificial intelligence company DeepSeek.

At the same time, they are lamenting aging infrastructure and cumbersome regulations in the United States, and an economy that can’t seem to make screws or drones, or the machines that manufacture them.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Some have called for an American DeepSeek project, published industrial manifestos full of references to China and even adopted China Tech’s gruelling “996” work culture — 9 am to 9 pm, six days a week.

“As China races forward, moving goods, people and information at machine speed, we risk being stuck in the past,” a recent blog post from venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz warned.

Among Silicon Valley leaders and policy-minded Democrats, there is a fascination with China. It’s a mix of curiosity, anxiety and envy. Long-held assumptions about China are being re-evaluated.

Suddenly, Chinese firms once dismissed as copycats are being studied for lessons on efficiency and scale. China’s top-down, state-led system is being reframed not as a political liability but as a model of efficiency and execution.

Both narratives — China as cheater and China as colossus — are simplistic reactions to something far more complex. Yet their popularity reveals something deeper about the American psyche as the nation struggles to adjust to a world where it is no longer the uncontested source of technological progress.

“For Americans, the idea that the future is now being created elsewhere — not in the United States — is a hard reality to accept,” said Afra Wang, a Silicon Valley-based tech writer. “This isn’t just about technology; it’s a question of identity.”

That identity crisis touches more than tech. It informs the views of so-called abundance Democrats frustrated by America’s inability to build housing or high-speed rail, as American tourists post social media videos of China’s bridges, trains and skylines.

The new admiration for China highlights both how little Americans understand about the country and how disillusioned many have become with their own. By holding China up as a mirror, America is seeing its own strengths and weaknesses more clearly than it has in decades.

Tech leaders are right to be alarmed. The old American model — we innovate, we build, we export — collapsed after the United States outsourced much of its manufacturing capacity.

Now America mostly designs while China increasingly embodies that earlier American model of building and producing. In a tense geopolitical environment defined by supply chains, the ability to manufacture has become both strategic and existential.

The challenge goes beyond traditional manufacturing. Integrating artificial intelligence with hardware is essential. Machines today are “the hardware version of software; they are the embodied version of AI,” said Marc Andreessen, a venture capitalist. “The car is not just steel and glass anymore — it’s a robot on wheels.”

American companies are racing to build machines more intelligent than humans. Yet if Silicon Valley studies China closely, it will find that China’s AI industry is not obsessed with artificial general intelligence, or AGI. Chinese entrepreneurs are focused on applying AI to services, devices and manufacturing.

I talk to a lot of people who work in the tech industry in China. Rarely do they mention AGI.

In an opinion essay in The New York Times, Eric Schmidt, the former Google chair, and his colleague Selina Xu urged Silicon Valley to be less obsessed with AGI and to learn from their Chinese peers to help integrate AI into daily life.

This is yet another example of China’s pragmatism versus America’s idealism.

American policymakers and Silicon Valley need to assess China and its tech sector realistically — its strengths and limits and what truly lies behind its efficiency and scale. China’s tech scene, like America’s, has visionaries and frauds, triumphs and dead ends.

The current narrative risks swinging from underestimation to overestimation.

Part of the reason American tech leaders amplify China’s capabilities, or its threat, is to pressure Washington into squeezing their Chinese peers with tariffs and regulation, and to win federal funding.

By framing China’s rise as an existential challenge, they can push the government to pour money into their industries. The more they can alarm U.S. politicians and the public, the greater their leverage, and the more power they ultimately gain.

Alexandr Wang, when he was CEO of the start-up Scale AI, urged President Donald Trump to expand federal AI support to match China’s investment “in a new kind of technological arms race.”

Jensen Huang, CEO of Nvidia, has claimed that Chinese chips are only “nanoseconds” behind and that China is not trailing the United States in AI. Such assessments drew scepticism in both countries, but they reveal how China has become the default benchmark in nearly every frontier field.

Yet Silicon Valley’s China conversation often overlooks contradictions at home. Some of the same leaders urging a US revival also support policies that undermine it: cutting university funding, tightening visa rules for skilled immigrants and waging trade wars that disrupt supply chains with allies like Canada and Mexico.

While the United States debates how to rebuild, China is doubling down on government support of research and development.

But for all its strengths, China’s system carries enormous costs. The same state-driven model that builds record-breaking bridges has left provinces buried in debt. Behind the polished image of AI labs and high-speed railways lie stagnant wages and a frayed social safety net.

China’s rise is real, but it’s not boundless. Its achievements coexist with deep structural flaws, just as America’s weaknesses coexist with enduring strengths.

Silicon Valley’s China envy ultimately says more about America than about China. It reflects a nation grappling with its lost confidence.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times