Ryan Borgwardt: Kayaker accused of faking his own death is alive, authorities say

Ryan Borgwardt —the husband and father of three accused of staging a kayaking accident so he could fake his death — is alive and talking with investigators from an unknown location.

Ryan Borgwardt — the 44-year-old husband and father of three accused of staging a kayaking accident so he could fake his death, abandon his family and start a new life — is alive and talking with investigators from an unknown location overseas, authorities said Thursday.

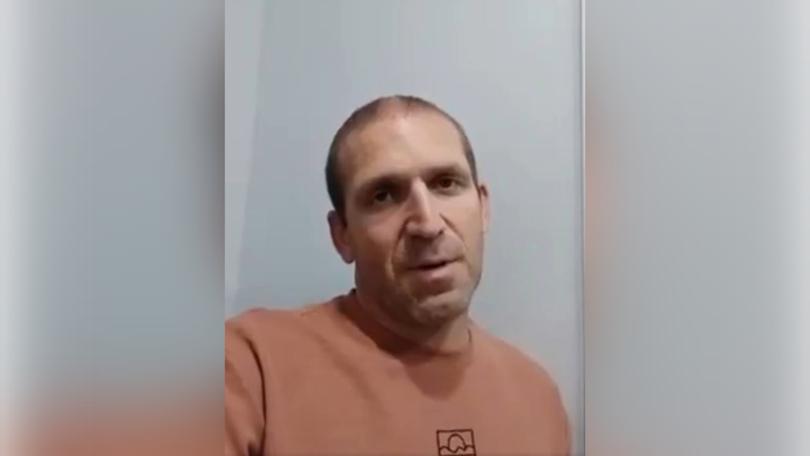

Green Lake County Sheriff Mark Podoll said his office has been communicating with Borgwardt over the past week and a half, including through a proof-of-life video Borgwardt sent him that the sheriff played for the public.

“I am safe, secure — no problem,” Borgwardt says in the 25-second video before panning the camera to show off what he said was his apartment.

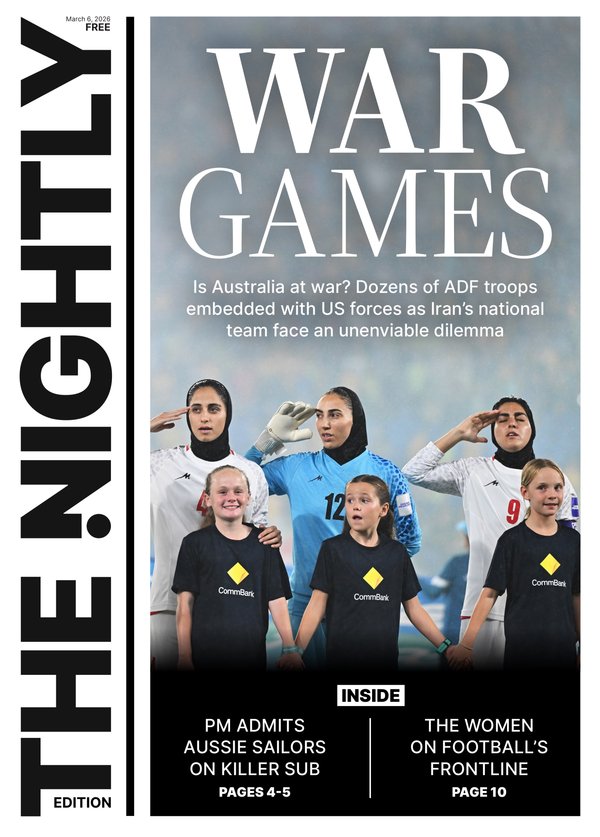

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It’s the most recent twist in a bizarre three-month saga that started in August when Borgwardt didn’t return from a Sunday kayak trip to Green Lake in Wisconsin. His disappearance sparked a search that turned up his kayak, vehicle and driver’s license, but despite weeks of looking, never recovered his body. Investigators determined he had faked his death, and on Thursday, Podoll revealed they believe Borgwardt is in Eastern Europe but have not been able to home in on his location.

At a Thursday news conference, the sheriff again pleaded with him to return to his wife and children, who very much want their husband and father back in their lives.

“He needs to return home to his children,” Podoll said. “If he chooses not to return on his own free will, I think the message is very clear.”

Podoll said Borgwardt has helped investigators fill in gaps about how he pulled off his caper — if they believe him.

Borgwardt told them he brought a child-size inflatable boat with him on Aug. 11 when he took his kayak out on Green Lake. After flipping the kayak and dumping his phone in the water, he paddled the inflatable boat to shore, got on an e-bike that he had stashed at the boat launch and rode through the night to Madison, some 70 miles away. There, he said, he boarded a bus to Detroit, then crossed the Canadian border and went to an airport, where he got on a plane. It wasn’t immediately clear how he crossed the border without drawing suspicion.

Investigators said they’re still trying to find out the location of the airport and Borgwardt’s destination.

Sheriff’s office investigators will probably request prosecutors charge Borgwardt with obstruction of justice, Podoll said, adding that he would not comment on what charges federal law enforcement might bring. The sheriff’s office spent between $35,000 and $45,000 investigating his disappearance and searching for his body, he said. That amount does not include the cost borne by Bruce’s Legacy, a group that helps authorities find the bodies of drowning victims. Keith Cormican, director of the private organization, spent 28 days over the course of two months scouring the lake in his boat, Podoll said.

The search for Borgwardt started early the morning of Aug. 12 when a sheriff’s office in Wisconsin got a call that he had gone kayaking at Green Lake the day before and never came home, Podoll said at a Nov. 8 news conference.

Over the next couple of days, deputies and others found Borgwardt’s van and trailer near a boat launch on the southwestern part of the lake, his capsized kayak and life jacket in the deepest part of the lake, his fishing pole at the bottom of the lake and his tackle box, which contained his keys, license and wallet, Podoll said.

All evidence suggested that Borgwardt had drowned.

But no one could find his body. Law enforcement officers, volunteers and a nongovernmental organization spent months scouring the lake, the sheriff said. They used sonar to plumb the 7,600-acre lake’s depths - 220 feet in some spots, flew drones to survey its surface and surroundings, and brought in cadaver dogs, hoping their noses would succeed where machines had failed, he added.

Still, no body.

On Oct. 7, Podoll told his investigators that they needed to shake up the probe. They started digging into Borgwardt’s background and soon discovered something unexpected: Canadian authorities had run his name in the days after he disappeared, the sheriff said.

Podoll contacted the FBI, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Department of Homeland Security and the Wisconsin Department of Justice.

A digital forensics analyst from the Wisconsin Department of Justice searched Borgwardt’s laptop, which his wife had given to investigators, Podoll said. The analyst discovered that Borgwardt had been communicating with a woman in Uzbekistan before his disappearance and had made inquiries about moving money to a foreign bank, the sheriff said. Borgwardt also allegedly replaced the hard drive on his laptop before the kayaking trip.

Investigators also found out that Borgwardt had taken out a $375,000 life insurance policy in January, the sheriff said.

Investigators concluded that Borgwardt hadn’t drowned and had instead spent months meticulously and secretly plotting to stage his own death and then abandon his family for a new life.

He was going to just try to make things better, in his mind.

At the Nov. 8 news conference, Podoll announced his findings. The sheriff conceded that he still didn’t know where Borgwardt was but nevertheless delivered him a message.

“Ryan, if you are viewing this, I plead that you contact us or contact your family,” the sheriff said. “We understand that things can happen, but there’s a family that wants their daddy back.”

Borgwardt staged his death because of myriad “personal matters” that were plaguing him, Podoll said, declining to go into detail about what those were. He told investigators that the $375,000 life insurance payout was supposed to go to his family.

“He felt this was the right thing to do,” Podoll said, adding: “He was going to just try to make things better, in his mind.”

The best thing for Borgwardt to do now is to come home to “clean up the mess he has created,” the sheriff said, adding that Borgwardt’s biggest concern in doing so is how “his community is going to react to him” now that his scheme has been laid bare.

Given that authorities don’t know where he is, it’s unclear what power they have to bring him home. For now, Podoll said he is leaning on the tools available to him, which seem to be a combination of emotional appeal and guilt trip.

“We keep pulling at his heartstrings,” the sheriff said.

The case is also pulling the sheriff’s heartstrings. Podoll got choked up at Thursday’s news conference during his plea to Borgwardt to reunite with his family.

“Christmas is coming,” Podoll said, his voice straining, “and what better gift could he give his kids than to be there for Christmas?”

© 2024, The Washington Post