Anzac Day 2024: WWII veterans Fred Marshall, Ron Dix and Frank Quinlivan reflect on their years of service

In the dark days of World War II when the nation’s very existence was under threat, they stood up to be counted.

The debt we owe them remains undiminished by the passage of time.

And the contributions of Fred Marshall, 99, Ron Dix, 99, and Frank Quinlivan, 98 are as clear as ever.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Before war broke out in 1939, Mr Marshall had been working on a farm at Kojonup, southeast of Perth, driving teams of horses behind a plough.

He enlisted in the aircrew reserve when he was 17 in 1941 and in November 1942 went into the RAAF full time.

As to what drove him to enlist: “The authorities asked us that question and they didn’t like you to say anything else but ‘for the king and country’,” Mr Marshall said.

“I just wanted to learn to fly too.”

When he graduated he was still considered too young to be sent overseas, so he was posted to air observers school in South Australia as a staff pilot.

When he turned 19 he went on to Sydney then across the Pacific on a US Liberty boat, across the US on a Pullman train, across the Atlantic on the Queen Elizabeth I and then to a depot at Brighton, England.

“The first thing we did when we got to Brighton and the German bombers came over was rush out and watch them in the searchlight,” he said.

“Then things started to clang down on the roof and we wondered ‘what the devil is that?’ — oh that’s the shrapnel from the anti-aircraft guns we better go inside.”

He was one of three pilots sent to a Lancaster station on England’s east coast to work in a control tower and then went on to an advanced flying school in Cheshire.

He recalled he was there on D-Day.

“We woke up one morning and the sky was full of aircraft and they were all facing towards France,” Mr Marshall said. “It was a turning point of the war.”

Mr Marshall then went to Upavon where he trained to be a flying instructor.

Despite the dangers of the times, he said there was some compensation — the pleasure of flying over the English landscape remained with him.

He then joined an advanced flying unit in South Cerney in Gloucestershire as an instructor.

Mr Marshall came back to WA after the war and went back to farming with his parents at Kojonup.

Mr Dix had left Perth Modern School when he was 15 to work at his grandfather’s printing business.

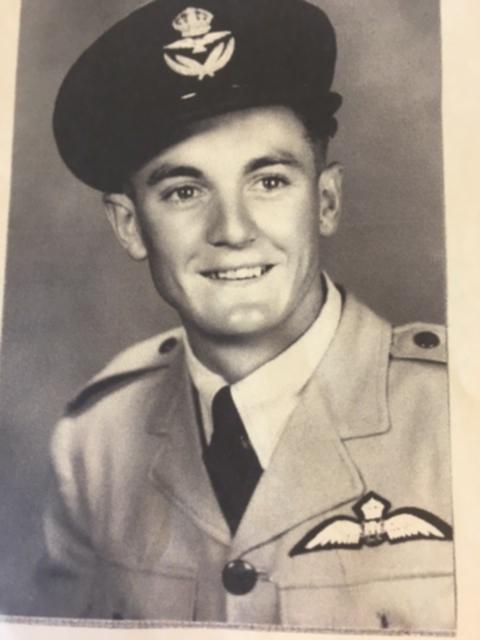

He joined the air cadets and then the Air Force as soon as he was able and was selected to train as a pilot.

That took him to flying schools at Cunderdin and then Geraldton and then on to learn navigation in Victoria.

Mr Dix joined a squadron patrolling the east coast out of Sydney in Avro Ansons, on the lookout for Japanese submarines.

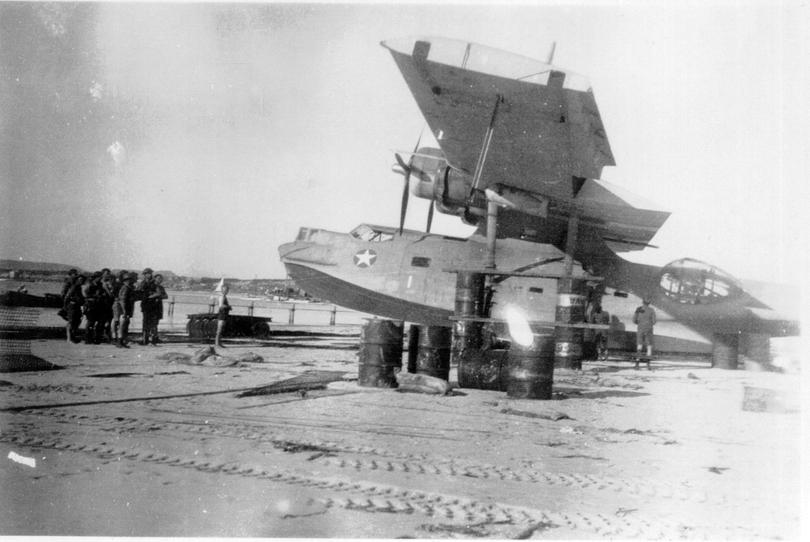

He then switched to Catalina flying boats which flew dangerous missions to Australia’s north, laying mines in enemy waters.

Mr Dix was the second pilot and was part of a major operation in which the Cats — painted black — flew under cover of darkness to lay mines in Manilla Bay as part of preparations for an attack on Japanese forces in the Philippines capital.

The mission saw 25 RAAF Black Cats take to the sky at once, accompanied by a US Navy Catalina tasked with jamming enemy radio.

As they dropped their mines in radio silence, the harbour was filled with the flickering lights of local fishing boats.

The mission was a success but it was not without tragedy.

One Catalina, The Dabster from 43 Squadron, did not make it back and nine men were lost.

After the war, Mr Dix went back to working in his grandfather’s printing business and finally took it over.

The memory of his time in the RAAF is strong.

“It was a small time in my life but it was a big event,” he said.

“It changed my whole life because I lost my father when I was 12 and so I didn’t have a father to show me what to do or tell me what to do, and the air force did that for me.”

He had grown up fast in those years.

Frank Quinlivan had been at the University of WA before he joined the Navy in 1943 and “hoped for the best.”

After completing his training he was sent onto the Destroyer, HMAS Warramunga and his job was to plot on a chart any threats picked up by radar and underwater signals.

The Warramunga served with the US 7th Fleet in some of the major battles of the war as the Japanese forces were driven back towards Japan and the Philippines was liberated in 1945.

They included actions around New Guinea and the battle of Leyte Gulf — often considered history’s largest naval battle — which provided crucial support to amphibious landings on the Philippines — and also at Lingayen Gulf, north of Manilla.

Among the roles the ship was given was to rescue downed aircrews.

“We had machine gun fire and bombs dropped on us, that was par for the course,” Mr Quinlivan said.

And there was also the danger of being targeted by a “Kamikaze” plane.

But fortunately, he emerged unscathed and left the Navy in 1946 after the war’s end.

Mr Quinlivan then trained as a teacher and worked at numerous schools around the State.

All three men were humble about their contribution to the war effort.

As Mr Quinlivan noted: “You just got on with whatever you had to do.”

The trio all played golf well into their 90s at Cottesloe Golf Club.

And they will unite again when they attend the club’s regular Anzac Day service.