Australia’s economy will have to face up to the great productivity puzzle

It was the word on every CEOs lips at the country’s largest investor event, so why can’t Australia work it out?

Across the three days of Macquarie Bank’s annual chief executive roadshow, one answer kept cropping up in response to The Nightly’s question of what Labor should focus on now it had a renewed mandate: productivity.

Productivity is one of those terms that raises more questions than answers, which is probably why so few people engage with it as a concept.

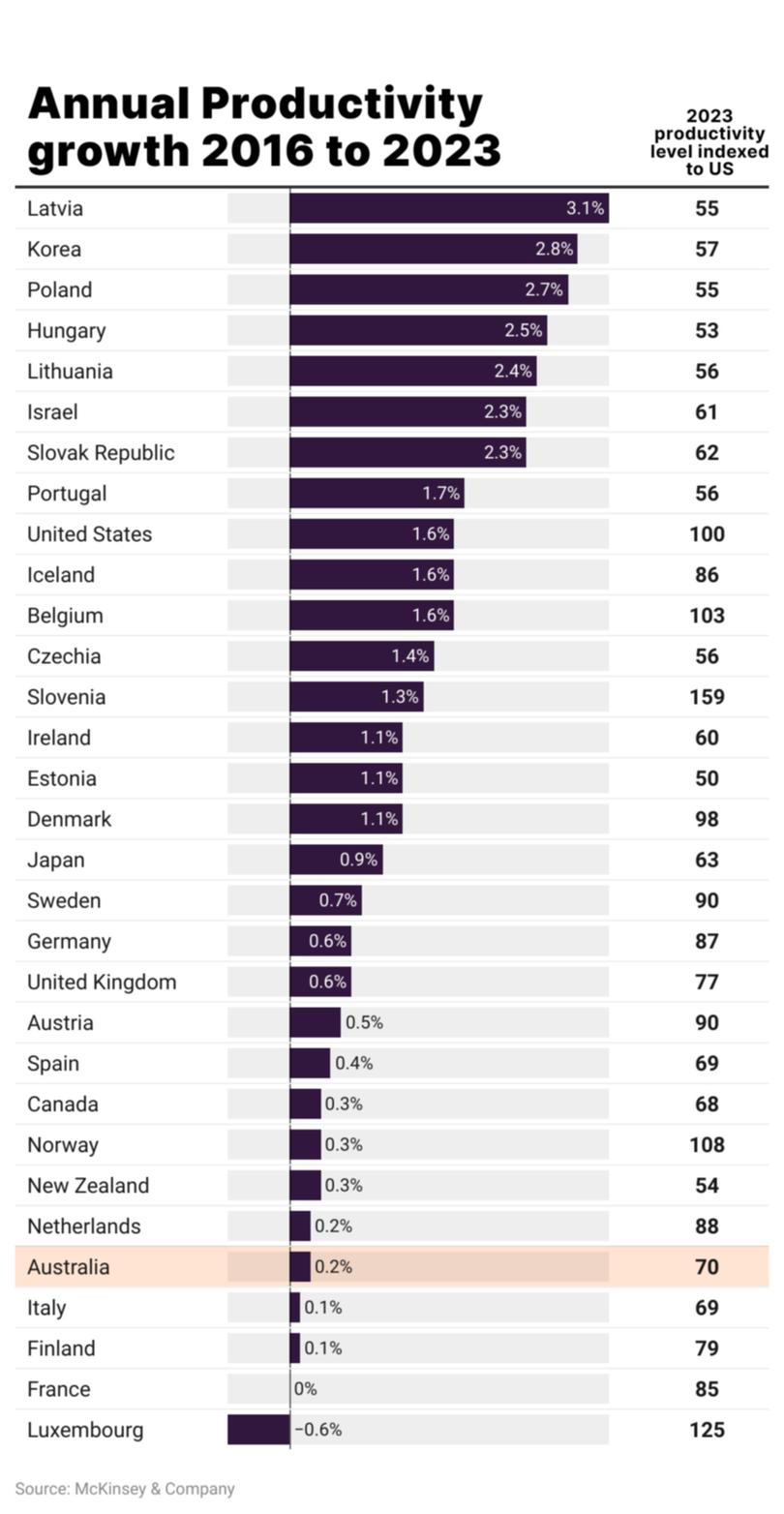

Which is a problem, because Australia’s productivity is dreadful.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Australia has seen productivity not only stagnate at zero growth since 2016, but go drastically backwards in the past year to be down 1.2 per cent.

A huge reason for that has been the massive growth in public spending, which now accounts for 28 per cent of all hours worked, larger than the UK, New Zealand or France.

Mathematically it is a negative for productivity, as it is almost impossible to measure the value of better care in a hospital or aged care facility. Some economists argue that it’s a misleading statistic, as traditional productivity calculations fare much better at measuring industries like manufacturing, where there is a clear dollar output on each widget against labour hours taken to produce it.

Dr Jenny Gordon, a non-resident fellow at the Lowy Institute who spent a decade at the Productivity Commission, calls it the sourdough effect.

“So this was a conundrum we had about artisan baking. Productivity is much lower because it takes more workers and capital (to) produce a loaf of bread, but the quality of the loaf of bread is so much better,” Dr Gordon said.

“The same idea applies on the services side where the quality of a coffee compared to when I was a kid is completely chalk and cheese.”

Despite the challenges of valuing intangibles like service quality, productivity is still the best measure we have, according to McKinsey partner Benjamin Stretch.

“There’s no stronger link between the measure of productivity as it is today, and income growth, higher real wages and higher living standards. If you go back through time, that relationship is as strong as ever,” Mr Stretch said.

That correlation between productivity and living standards should have every Australian very worried.

Wage growth without productivity leads to inflation, something that every Australian would like to see far in the rear view mirror.

Productivity generates greater tax revenue both at the worker and company level, money critically needed as the country faces decades of budget deficits as spending on an ageing population is expected to explode.

“Australia has chosen to have a larger non-market sector over time, and that’s a choice of politicians and voters. But if we want to have that sort of larger non-market sector, you need a market sector that’s more productive to pay for it,” Mr Stretch said.

The problem for Australia is our market sector - private companies - has not been productive enough.

New research from McKinsey has found that those innovative firms don’t just become household names — think Apple, Amazon or EasyJet — they drag the rest of the economy along with them in the innovation stakes.

McKinsey analysed 8,300 companies across the US, UK and Germany and found that fewer than 2 per cent of large firms are responsible for 63 per cent of productivity growth. In the US, just 44 firms accounted for nearly 80 per cent of all productivity gains.

These firms excel at making bold strategic moves, invest heavily in research and development, reallocate capital toward high-growth areas, enter new markets, or overhaul their business models.

It gives these ‘standouts’ a greater share of the pie, but McKinsey has found they also lift other companies up in the process.

“Apple itself has been responsible for about 10 basis points of productivity growth in the US alone. And the way it does that is through unlocking the innovation and productivity of other firms by the products it produces. And so what we see is that these big firms are catalysts for and sort of almost like enablers of second- and third-order productivity in small firms,” Mr Stretch said.

Unfortunately for Australia, the last time the country had such standouts was more than a decade ago.

During the height of China’s economic rise, the big miners were drivers of productivity from the early 2000s to 2010s thanks to massive capital expenditure and investments in operational excellence. Australia’s financial services firms achieved a similar feat, right up until the Royal Commission into financial misconduct tied them up in regulation.

In some ways, Australia is also a victim of its own success. It has gone the longest without a recession, almost 30 years and twice that of the next most fortunate, Korea.

The success of the minerals sector, currently accounting for one-third of company tax revenue, has kept things ticking along with the result that no one seems willing to rock the boat.

“I think the mindset of not only our leaders, but I think the populace in Australia at the moment is: ‘we’ve got so good right now, don’t put that at risk’,” Mr Stretch said. “And I think that’s permeated down into this mindset of, quite frankly, a bit of complacency.”

Complacency was the word raised by Shemara Wikramanayake, chief executive of one of Australia’s few standout firms, Macquarie, who noted that Australia had managed to skate through the most recent crises relatively unscathed.

It has also meant that the country is overweight in smaller, less efficient firms, while the larger firms enjoy a comfortable monopsony.

Without that competitive pressure, companies have been investing in new capital at levels not seen since the 1990s recession, while R&D spending is falling and is now half that of US firms. Low innovation and the abundance of small firms was one of the key reasons Australia’s housing costs were so high, and pace of construction so slow, the Productivity Commission recently found.

The country’s superannuation sector may also be partly to blame, Mr Stretch said, pressuring firms to deploy capital into dividends rather than chasing risk.

“Over the last couple of decades, almost at least a decade, (there has been a) decline (in) investment into R&D and (a tendency to) rely more on the universities to invest,” Dr Gordon said. “We’ve also spread that investment out where every state and territory wanted a space centre or quantum computing. We need to concentrate the effort and create pockets of real R&D excellence.”

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has said productivity will be his focus in Labor’s new term, and it will need to be.

“We’ve had the uplift in living standards … the good budgets … the strong terms of trade, but we’ve lost the appetite and the ambition for the microeconomic reforms behind our strong economy. We don’t have, from really any corner of the economy, a clear vision of what’s next to underpin the next 20 years of growth,” Mr Stretch said.