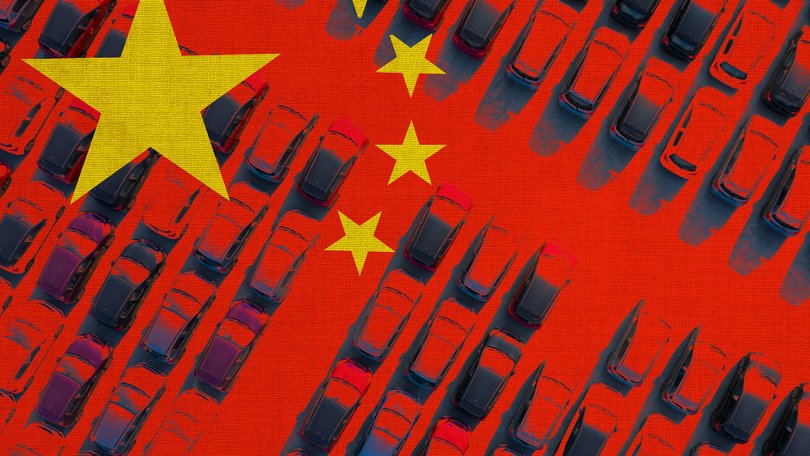

THE ECONOMIST: Chinese EV makers outpace BMW and Mercedes as brutal price war reshapes car industry

THE ECONOMIST: Ruthless discounting has left EV giants in a fight to survive.

During Germany’s big motor show in Munich, which ended on September 14, the city’s historic centre belonged to the country’s own champions.

In front of the neoclassical opera house, BMW showed off the new iX3, an electric SUV, atop a glittering plinth; at the Residenz, a renaissance palace, Mercedes-Benz built a vast design studio resembling a car grille to display a revamped GLC, another SUV.

But at the main exhibition halls in the suburbs, history was forgotten. There, young Chinese car firms outnumbered and outdid the local old guard.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.BYD, Xpeng, Changan and Dongfeng showed electric vehicles with advanced technology and prices that undercut Western models, or announced expansions making it clear that Europe is the main target in their worldwide export blitz. Yet Chinese ebullience in Europe contrasts sharply with troubles at home, where a long-running price war, caused by chronic overcapacity, is raging.

Its origins lie in the Chinese government’s success in first nurturing its carmakers and then propelling them to the fore of the global industry.

The government realised 15 years ago that its companies could not compete with foreign petrol power, but that an electric vehicle industry might thrive in a fast-growing home market if primed with enough subsidies and other support. The result was a surge of investment, dozens of new firms and a market where electric vehicles are likely to make up 60 per cent of sales this year.

Around 130 domestic firms now battle for sales, though few make cars in significant numbers. If their factories ran at full tilt for a year they could churn out twice as many cars as there are buyers. The consequence of overcapacity has been a savage price war.

The average car price has fallen by 19 per cent over the past two years, to around 165,000 ya ($34,650), calculates Nomura, a Japanese bank. Some models have seen one-off cuts of around 35 per cent. Although sales are still growing—at a forecast 7 per cent this year, to around 24 million vehicles — firms’ profits have dwindled or losses mounted.

In the first five months of 2025 total industry net profits (including those of foreign carmakers) fell by 12 per cent, year on year, to 178 billion yuan ($37b), according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Even successful domestic firms are feeling the pinch.

In the first half of the year, net profits fell by 14 per cent at Geely, a private firm with about a tenth of the home market. More surprisingly, on September 1 BYD, China’s biggest carmaker, reported a 30 per cent drop in net profits in the second quarter, even as revenues grew by 14 per cent. Suppliers are suffering too. Some are said to have shut down, as carmakers delay payments for up to six months.

Foreign firms, already struggling to keep up with Chinese firms’ speed of innovation, are suffering even more. They once dominated the market, but domestic brands’ share has climbed from 34 per cent in 2020 to 69 per cent in the first four months of 2025, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. The price war has hastened the foreigners’ slide. As Patrick Hummel of UBS, a bank, points out, they “can’t compete in a price war with locals”.

The carnage in a showcase industry is worrying the Chinese government. In May price cuts by BYD sparked another round of heavy discounts, prompting complaints, via state media and industry bodies, about “involution”, a term for destructive hyper-competition.

In June officials summoned carmakers to Beijing and told them to end price cuts and speed up payments to suppliers. Several big firms have pledged to pay within 60 days.

Yet no end is in sight. An executive at a Western carmaker in China thinks that low prices are here to stay. Even since the pleas to rein in discounts, price-cutting has continued, though in a less obvious way: Stephen Dyer of AlixPartners, a consultancy, notes incentives such as free insurance, zero-interest financing and free charging. Stella Li, a senior executive at BYD, says there are “too many” carmakers, close to 100 need to be “pushed out” and even if 20 remain that may be too many.

No such clear-out is imminent. The government has long tried to engineer mergers of big state-owned firms. In 2018 rumours circulated about a tie-up between Changan, FAW and Dongfeng.

Earlier this year a plan to bring together Changan and Dongfeng fell apart. Neither firm’s home province was prepared to play second fiddle, bearing the brunt of job losses and forgoing the economic activity and tax revenue that big car firms generate. The central government does not relish fights with local leaders to force through mergers.

A long tail of small, lossmaking local car firms, attracted to the industry by bumper growth in the 2010s, the availability of cheap credit and lavish incentives, may also sputter on, even though a handful of startups have gone bust. Such firms also provide employment and bring kudos for local party bosses, who will do anything to maintain their pet projects.

Buyers are unlikely to step forward—no other carmaker would want to acquire brands that are unknown beyond their region or take on additional capacity. Central authorities may be pressing local governments to stop funding these firms and some may not be able to keep cutting prices. But as Tu Le of China Auto Insight, another consultancy, notes, “bad companies aren’t going out of business fast enough”.

The price war may, however, make the strongest stronger still. Leading firms, such as BYD, Chery and Geely, and startups, such as Xpeng and Li Auto, are profitable or close to it. And tech firms such as Huawei and Xiaomi have successfully turned to making cars.

As an experienced observer notes, the best companies can adjust their cost structures to accommodate permanently lower prices. Many have also turned to exports to seek fatter margins.

Between 2021 and 2024, the number of cars shipped abroad quadrupled, taking China past Japan to become the world’s largest exporter, according to Rhodium Group, a research firm. In the first six months of 2025 exports hit nearly 3.5m, 18 per cent more than a year earlier.

Europe remains the main destination for Chinese electric vehicles despite the EU’s imposition of hefty tariffs in 2024 to counter what it regards as unfair competition.

In the first half of the year Chinese brands accounted for 5.2 per cent of sales in western Europe, up from 3.1 per cent the year before, says Schmidt Automotive Research. Sharpened by ruthless competition at home, the Chinese can withstand the EU’s levies.

By contrast, foreign carmakers that have relied on China as a source of profits are in a bind. America’s Ford and General Motors, protected by 100 per cent tariffs at home, face the prospect of a dwindling presence in China.

Japan’s Toyota has fared better than most but is also ceding ground in China. Nissan is in free fall.

European firms are losing out in China and face a similar fate on home soil. A continuing price war will force the best to become even more lean, efficient and innovative. And that means China’s most powerful firms will thrive, both at home and abroad.

Originally published as The brutal fight to dominate Chinese carmaking