THE ECONOMIST: Fleeting power of the supply shock as commodities slump after a brief lithium surge

THE ECONOMIST: Commodities momentum has drained drains as the market’s lithium surge is fizzling.

Commodity markets look deceptively simple. The prices of raw materials, unlike those of bonds or stocks, seem to move according to how much raw material there is — forget obscure data somewhere on a balance sheet.

When the supply of a commodity shrinks, prices go up. When supply expands, they go down. Inventories are buffers against shocks: when they are low, prices move more, and vice versa.

The problem is that supply shocks never quite live up to the initial excitement. Take, for example, lithium. In late July the white metal, which is mainly used to make batteries for electric vehicles (EVs), looked dull.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.For more than a year, a global glut had been keeping spot prices for lithium carbonate, the most traded form, near $US10,000 ($15,000) a tonne, 90 per cent below their peaks a few years ago. And it was summer, so investors were bored.

In early August China’s government shook them from their torpor by forcing Jianxiawo, a major lithium mine, to close after its permit expired. Soon it emerged that other mines also had licensing trouble. Investors became giddy. Was China finally curtailing capacity in an industry dogged by overproduction?

Lithium prices rose by over 8 per cent; outside China, the shares of lithium miners jumped by between 5 per cent and 30 per cent. But soon prices fell again. Most are now back near where they started, even though Jianxiawo remains shut.

To understand why, go back to 2022, when lithium spot prices surpassed $US80,000 ($121,000), setting records. To excitable sell-side analysts, the surge was down to an unstoppable campaign to replace the world’s petrol cars with EVs.

This, they argued, would keep lithium’s price stratospheric for many years. In fact, says Tom Price of Panmure Liberum, a bank, the rally was a one-off, triggered by old-fashioned carmakers starting to make EVs.

Even though most lithium is sold under multi-year contracts, they and their battery suppliers rushed to the thin spot market, exaggerating price moves.

Soon, however, everyone was stocked up. And it turned out that, once the post-pandemic consumption spurt was over, EV sales stopped growing so fast after all. As lithium demand fell accordingly, prices cratered.

Any potential spark to reignite the market would have to come from a supply shock. Eventually one arrived: by shutting the Jianxiawo mine, Chinese officials have trimmed up to 3 per cent from the world’s lithium supply. Yet even if it remains closed, the global market will end 2025 in surplus, says Adam Megginson of Benchmark Minerals, a data firm. And little new evidence has emerged that China aims to curb production. On August 29 lithium prices fell after a small mine in Jiangxi renewed its licence.

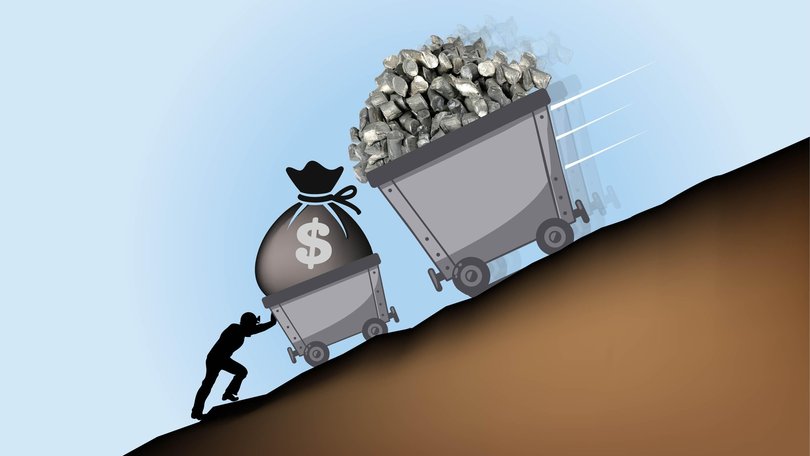

Lithium illustrates a broader point: in commodity markets, supply shocks are rarely a sound basis for investment. For a start, the decisions that cause such shocks are often political, and so can be swiftly and unpredictably undone.

In early July, after Donald Trump said he would impose levies of 50 per cent on copper imports — which make up half of America’s copper supply — prices set records on the country’s main commodity exchange. Then, in late July, America’s president exempted raw materials, including copper ores and refined copper, from the duties. Prices collapsed.

Moreover, supply problems are often resolved quickly. Refineries are repaired. Mines restart. When crucial waterways are blocked, tankers take new routes, as happened when Red Sea traffic became the target of Houthi missiles. And new supply can often be brought online quickly.

During the COVID pandemic, when lockdowns depressed demand for energy and building materials, producers curtailed supply. When lockdowns ended and demand rebounded, supply fell short, so prices jumped. Analysts were quick to hail a new commodity supercycle, but soon enough supply rose again. The rally ended.

Although some supply shocks do last, their effects can still dissipate fast, because high prices sap demand. In February the Democratic Republic of Congo, which supplies 70 per cent of the world’s cobalt — another battery ingredient — stopped exports for four months. It has since extended the ban until September, and cobalt prices have soared.

But they may soon come down, then stay low. Wary of a repeat, many carmakers are opting for batteries that use much less cobalt, or even none at all. The only solid foundations for commodity booms are structural shifts in demand. Those claiming otherwise are often trying to take punters for a ride.

Originally published as Why supply shocks are a trap for commodity investors