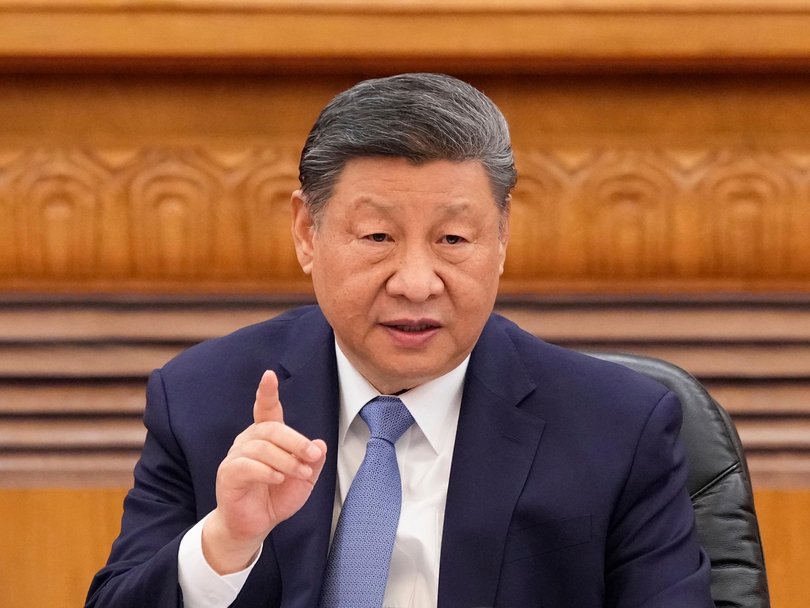

THE ECONOMIST: Xi Jinping’s weaponisation of rare-earth elements from China will ultimately backfire

THE ECONOMIST: Xi Jinping has put in place a system of export controls that seek to exploit China’s heft in global supply chains. The aim is clear.

Soon after the blockade started, the panic began. When China choked off the export of rare-earth elements in April, producers and politicians around the world were quick to sound the alarm.

The country provides 90 per cent of the world’s supply of refined rare earths, used to make the strong magnets inside almost anything with an electric motor, from vacuum cleaners to cars.

Ford halted a factory line in Chicago; carmakers in India and Japan curtailed production. The car industry is in panic mode, said one boss. Ursula von der Leyen, head of the European Commission, thundered against China’s dominance and blackmail.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.At first glance the use of rare earths as a weapon is working — and Xi Jinping, China’s supreme leader, is getting what he wants. After the flow of rare earths resumed, America’s president lifted controls on the sale of some Nvidia chips, and delayed a hefty increase in import duties; on August 11 America and China further extended their trade truce.

In July Mrs von der Leyen went cap-in-hand to Beijing, seeking looser restrictions.

But in the long term, China’s rare-earths weapon will backfire. The new controls are a sign of just how sophisticated China’s economic arsenal has become. After a political spat in 2010 it briefly blocked the exports of rare earths to Japan; in a fit of pique in 2020, it increased duties on Australian Shiraz and grass-fed beef.

Now, however, Mr Xi has put in place a system of export controls that seek to exploit China’s heft in global supply chains. A licensing scheme covering more than 700 goods, including manufacturing equipment and critical minerals, began operating in December. Officials keep careful track of the ultimate consumer of the products, and can revoke licences. Even though rare-earths exports have resumed in recent weeks, for instance, sales to Western armsmakers are still choked off.

The aim is clear. Mr Xi wants to indigenise supply chains, so that China is not at the mercy of its enemies for critical inputs — an effort that was turbocharged after America banned the export of advanced chips to China.

He also hopes to use China’s control of supply chains as a source of power over others. As long ago as April 2020 he told officials that dependency on China could be a deterrent against foreigners who would artificially cut off supply.

The difficulty for Mr Xi, though, is that export controls have unintended consequences. Confronted with a ban, companies and entrepreneurs find ways around the shortage.

China’s dominance in rare earths stems not from exclusive control of the world’s deposits, nor from the technological sophistication of the refining process, but instead from efficiency, scale and convenience. And the more it uses rare earths (or indeed other commodities) as a weapon, the more it will encourage others to find alternatives — weakening its future firepower.

Start with the nature of China’s chokehold. Despite their name, rare earths are relatively abundant; less than half of all known reserves are found in China. Refining is a painstaking and polluting business, but is not as technologically complex as advanced chipmaking. China’s grip on rare earths is therefore not as strong as the West’s on cutting-edge chips, and easier to work around. Indeed, until the 1980s, America was the biggest supplier of the minerals.

The dominance of China came about because it was more willing to accept the environmental consequences, and has since been cemented by its gargantuan size, which allows rare earths to be mined cheaply.

Efforts by China to restrict the flow of rare earths have already spurred efforts to find alternatives. After the spat in 2010, Japan invested in rare-earths mines and began building stockpiles; although it still imports rare earths from China, its dependence has fallen from 90 per cent to 60 per cent.

Earlier this year the Pentagon took a stake in MP Materials, a miner in California, with which Apple has signed a deal. All told, 22 new mining projects are expected to be up and running by 2030.

Trendy geoeconomic theory points out that even a small erosion of China’s dominance in rare earths could weaken its power disproportionately. Reducing its share from 90 per cent to 80 per cent may not sound like much, but it would imply a doubling in size of alternative sources of supply, giving China’s customers far more room for manoeuvre.

Even so, this diversification could still take years.

What could Western governments do to speed it up? They have a responsibility, of course, to secure their military supply chains. They could also streamline the process of approving mining permits (which in America can take up to a decade), and could revisit environmental rules. Lowering trade barriers would also help the rest of the world mimic China’s scale.

It would be a mistake, though, for governments to seek to protect the entire economy from the impact of shortages. That is because a far more powerful — and underappreciated — response to shortages is innovation.

Just think of how America’s chip controls have prompted Chinese firms such as Huawei and DeepSeek to develop new techniques, or how a cobalt crunch in 2022 quickly eased, partly as electric-vehicle-makers found ways to do without the metal. Similarly, startups across the West are now working on the recycling of rare earths, and on the development of alternative ways to make magnets and motors that do without them.

BMW and Renault, two European carmakers, already sell electric vehicles that do not use rare earths in their motors. Other companies could follow suit.

China’s restrictions will cause disruption as producers rejig their processes, but long-term alternatives do exist.

From rare to well done

The more China uses its rare-earths weapon, therefore, the weaker it will become. Time and again, enterprise and ingenuity have prevailed over attempts to control the flow of goods.

China itself learned that lesson as its technology firms responded to America’s export controls on chips. It may now be about to learn it again.

Originally published as Xi Jinping’s weaponisation of rare-earth elements will ultimately backfire