THE ECONOMIST: Google challenges Nvidia dominance as AI chips shift, custom TPUs threaten its invincible aura

THE ECONOMIST: Google has pierced Nvidia’s aura of invulnerability.

No company has benefited more from the craze for artificial intelligence than Nvidia, these days the world’s most valuable company. Over the past three years investors have bid its shares into the stratosphere on the belief that its dominance of the market for AI chips is unassailable. Rival chipmakers and startups alike have tried to elbow their way into its business, with little success.

Now, however, one of Nvidia’s biggest customers has emerged as its fiercest competitor yet. This month Google, which pioneered the “transformer” algorithms underpinning the current AI wave, launched Gemini 3, a cutting-edge model that outperforms those of its biggest rivals, including OpenAI, on most benchmarks.

Crucially, Gemini 3 was trained entirely on Google’s own chips, called tensor-processing units (TPUs), which it has begun peddling to others as a far cheaper alternative to Nvidia’s graphics-processing units (GPUs).

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Last month Anthropic, a model-maker, announced plans to use up to one million of Google’s TPUs in a deal reportedly worth tens of billions of dollars.

Reports that Meta, another tech giant with big AI ambitions, is also in talks to use Google’s chips in its data centres by 2027 has caused Nvidia to shed more than $US100billion ($155b) in market value, some 3 per cent of its total, since the close of trading on November 24.

Nvidia’s customers have a big incentive to explore cheaper alternatives. Bernstein, an investment-research firm, estimates that Nvidia’s GPUs account for over two-thirds of the cost of a typical AI server rack. Google’s TPUs cost between a half and a tenth as much as an equivalent Nvidia chip.

Those savings add up. Bloomberg Intelligence, another research group, expects Google’s capital expenditures to hit $95 billion next year, with nearly three-quarters of that being used to train and run AI models.

Other tech giants including Amazon, Meta and Microsoft have also been developing custom processors, and last month OpenAI announced a collaboration of its own with Broadcom, a chip designer, to develop its own silicon.

But none has progressed as far as Google. It began designing its own chips more than a decade ago. Back then, Google’s engineers estimated that if users ran a new voice-search feature on their phones for just a few minutes a day, the company would need to double its data-centre capacity, a prediction that spurred the development of a more efficient processor tailored to Google’s needs. The company is now onto its seventh generation of TPUs.

Jefferies, an investment bank, reckons Google will make about 3m of the chips next year, nearly half as many units as Nvidia.

For Nvidia’s other customers, however, switching to Google’s chips will not be straightforward. Nvidia’s edge lies partly in CUDA, the software platform that helps programmers make use of its GPUs. AI developers have become accustomed to it.

And whereas the software surrounding TPUs has been created with Google’s own products in mind, CUDA is intended to cater to a wide range of applications.

What is more, reckons Jay Goldberg of Seaport Research Partners, an industry analyst, there may be a limit to how willing Google will be to sell its TPUs, preferring instead to steer its would-be customers to its lucrative cloud-computing service. To stymie its AI competitors, Google may also be tempted to keep prices for its chips high.

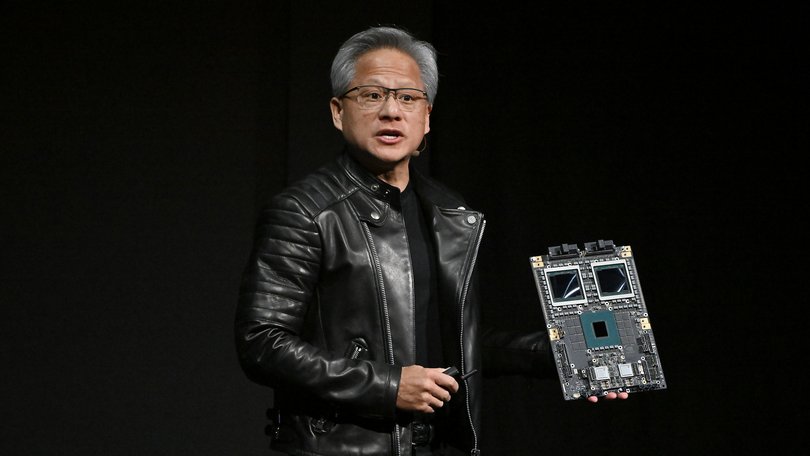

All this may explain why Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s boss, does not seem especially worried. He has described Google as “a very special case”, given it began developing chips long before the current AI wave, and has dismissed other efforts as “super adorable and simple”. He is also betting on flexibility.

The transformer architecture underpinning today’s AI models is still evolving. GPUs, which were originally developed for computer games, are highly adaptable, letting AI researchers test new approaches.

Nvidia no longer looks as invulnerable as it once did. But its strength should not be underestimated.

Originally published as Google has pierced Nvidia’s aura of invulnerability