THE ECONOMIST: Why investors are becoming increasingly fatalistic amid rising market volatility

THE ECONOMIST: Everyone knows share prices have a long way to fall. Even so, getting out now might be a mistake.

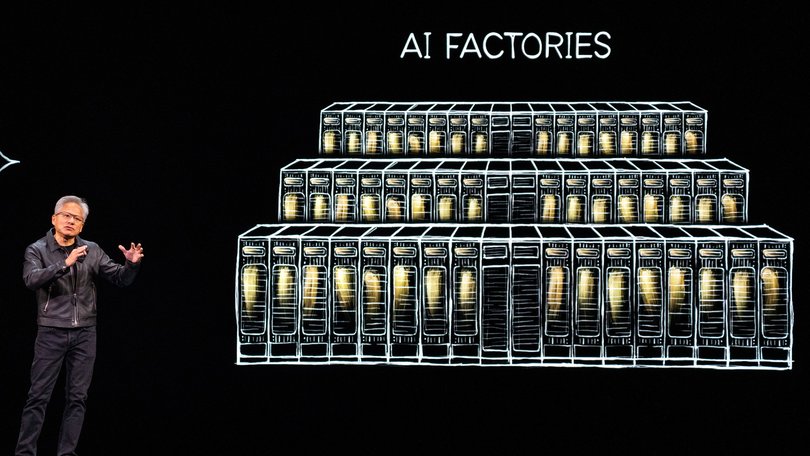

Sales of Nvidia’s most advanced chips “are off the charts”, said Jensen Huang on November 19, while reporting his firm’s highest-ever quarterly revenues.

The boss of the world’s most valuable company had much to celebrate. It raked in $US57 billion ($A88b) in the three months to October, at a gross profit margin of over 70 per cent — the stuff of investors’ dreams. Yet the following day, Nvidia’s share price fell by 3 per cent. It is now 13 per cent below its peak in October.

Across markets, the mood among shareholders has shifted from bullishness to fatalism.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Stocks have been soaring for years, fuelled by hopes that artificial intelligence will supercharge profits — hopes that most professional investors now think have become overly optimistic. In the grand scheme of things, the recent sell-off is eminently bearable.

Although the S&P 500 index of big American firms is down by 4 per cent since its peak in October, it is also up by 84 per cent since a trough in 2022.

But for stocks to fall when the news is good is a troubling hint that a long bull market might at last be running out of steam. Traders are on edge, and in the coming week will be alert to signs that the sell-off might accelerate.

One red light is already flashing: markets seem unusually uncertain of how to interpret new developments.

The morning after Nvidia’s earnings report, for instance, the firm’s share price leapt by nearly 5 per cent — and the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq, a tech-heavy index, jumped, too — before all three began to slide and closed in the red. Meanwhile, the VIX, which measures the range in which traders expect the S&P 500 to move and is otherwise known as Wall Street’s “fear gauge”, was all over the place.

A reading of 20 means that in a year’s time, traders think it likely the share-price index will be somewhere between 20 per cent above and 20 per cent below its current level. In normal times, this estimate varies by no more than a percentage point or two from day to day.

On November 20 it swung from 19 to 28 in under three hours. Investors, in other words, are no longer confident that even barnstorming results like Nvidia’s can keep pushing share prices higher, since valuations have risen so far already.

Another warning sign would be for investors’ usual boltholes to become unreliable. True, lately the dollar has resumed its role as a haven and risen in value (unlike in April after President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day”, when it plunged along with stocks).

But the price of gold, a traditional hedge against volatility, peaked in October and has fallen by 7 per cent since, barely budging during last week’s ructions.

Gold has spent recent years on its own blistering bull run, with its October peak marking an all-time high and raising worries that the precious metal is itself in a bubble.

If investors in supposedly riskier assets cannot rely on gold to hedge their losses, the next crash will be painful indeed.

The third bad omen would be for “normal” correlations between different assets’ prices to break down. Just now, Japan is the focus of such worries. Its currency, another erstwhile haven, sold off amid the past week’s turbulence, even as Asian share prices also fell and Japan’s borrowing costs rose.

The ten-year yield on Japanese government bonds hit 1.8 per cent on November 20, its highest since 2008; the 30-year yield reached 3.4 per cent, its highest ever.

This is exactly the dynamic, reminiscent of emerging markets, that panicked investors when exhibited by America’s currency, shares and Treasury bonds in the spring. Should it continue — or worse, spread to other markets — traders will start panicking again.

For now they are not, despite the mounting threats to their profits. Perhaps that is because they remember the biggest challenge of the dotcom boom: the sheer number of times share prices plunged before recovering and then rocketing upwards again.

Between the start of 1995 and the bubble’s peak in 2000, the Nasdaq went through peak-to-trough corrections of more than 10 per cent at least 12 separate times.

Over the same period, it offered cumulative gains of nearly 1100 per cent to those who kept their nerve and refused to sell.

Today’s investors can hardly fail to wonder whether last week’s sell-off might accelerate. They also know that, even if it does, getting out now could prove a mistake.

Originally published as Why investors are increasingly fatalistic