THE ECONOMIST: Inside America’s financial clash of the titans

The new giants of Wall Street are breaking down old boundaries.

“The marked increase in the popular participation in securities transactions has definitely placed under the control of financiers the wealth of the Nation.” Thus concluded the Senate’s report into the causes of the stockmarket crash of 1929. The world is again in an age of truly powerful financiers. Some giants of today simply reflect the size of America’s economy. JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank, is big because America is. But others owe their heft to how the structure of markets has changed.

Index-based funds and other forms of passive investing in public markets have risen inexorably. That has been to the advantage of BlackRock and Vanguard, the asset managers which dominate low-cost investment products. Non-bank players in private markets — markets which trade in privately held companies and extend illiquid loans — have also grown massively. Apollo, Blackstone and KKR together have $US 2.6 trillion ($4trn) of assets under their control, up from $US570 billion a decade ago, largely due to expanding their lending activities.

The combined market capitalisation of these firms and BlackRock has increased over the same period from $US125b to $US500b — that is from 10 per cent of the value of America’s banks then to 21 per cent now. Some huge hedge funds, like Citadel and Millennium, have absorbed capital and brainpower from the rest of their industry. Last year Jane Street, a hedge fund, earned as much trading revenue as Morgan Stanley, a bank.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.These giants’ proportionally sized spheres of influence overlap. Apollo resembles a life insurer more than it does the private-equity fund it used to be (and is still treated as). The largest venture-capital firms have grown from small partnerships to look like their bigger cousins in private equity (General Catalyst, one such firm, has even set up a wealth-management division).

Some big hedge funds provide liquidity as market-makers, a role historically dominated by banks, in addition to trading on their own account. And banks are fighting back. Goldman Sachs has reorganised itself to better take on private-credit lenders.

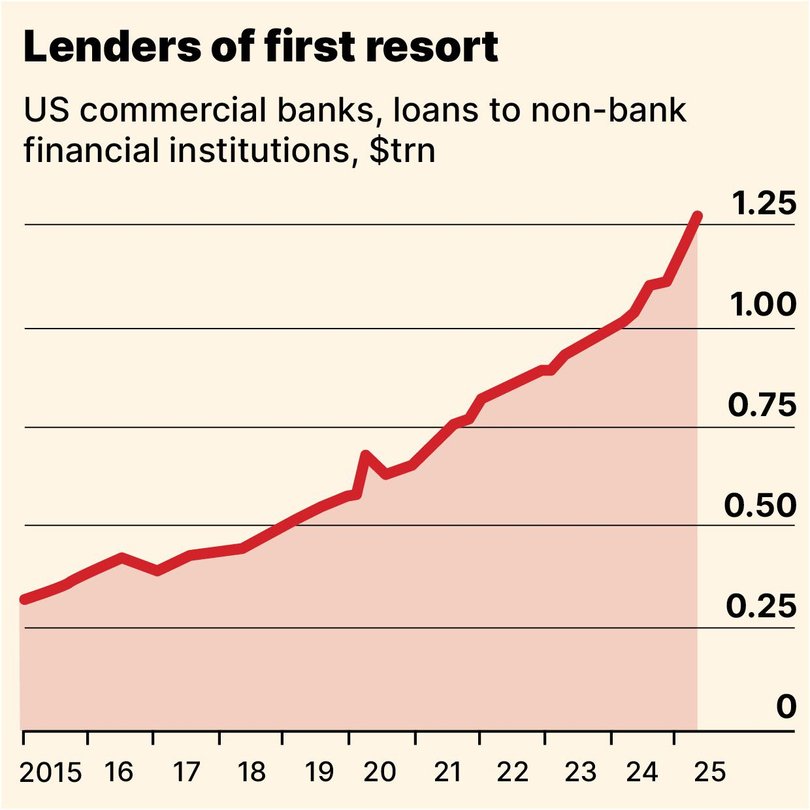

The revolutionary effect of these firms is clearest at the boundaries which run through the financial system. One is between banks and non-banks. Bankers are busily greasing the wheels of the firms that take the bets they used to. Loans to non-bank financial institutions have doubled since 2020 to $US1.3trn and account for a tenth of all bank lending. Hedge-fund borrowing from the prime-brokerage divisions of banks has increased from $US1.4trn to $US2.4trn over the same period. Lending partnerships between banks and private-credit firms have proliferated.

Another boundary is that between public and private markets. Borrowers now choose between “public” bond and loan markets, where debt changes hands frequently, and private ones, where loans are hardly traded at all. These days more asset managers are operating in both markets.

The third boundary is between retail and institutional investors. Retail investors can now access products as complex as anything changing hands on a trading floor. Exchange-traded funds (ETF), once considered staid investment vehicles, are booming as asset managers structure them to offer individuals the sort of risks and rewards one might find in a casino. (Cryptocurrencies only fuel the speculative fever.)

We’re not so different, you and I

The parable of BlackRock neatly illustrates this messy picture. Now the world’s largest asset manager, it opened shop in 1988 as part of Blackstone, a private-equity firm. They broke up in 1994, and for decades thereafter, the firms represented alternative visions of finance.

BlackRock’s world was one of public markets, low fees, retail investors and the overbearing socially conscious capitalism of its founder, Larry Fink. Blackstone meanwhile focused on private markets and institutional investors. Stephen Schwarzman, its founder, is the archetypal buy-out baron.

Now the firms are converging. Blackstone pitches its products to individual investors. BlackRock has jumped the other way, into private markets. Last year the firm spent the equivalent of a quarter of its market capitalisation on HPS, a private-credit lender originally carved out of JPMorgan; Preqin, a data firm; and Global Infrastructure Partners, which does what it says on the tin. It even atoned for its wokeness by bidding for strategically important ports in Panama currently owned by CK Hutchison, a firm based in Hong Kong, earning it praise from Donald Trump.

The sum of these changes is an American economy increasingly funded by capital markets instead of by banks. This new-look financial system is certainly innovative. But is it resilient? Those at its apex sing its praises by comparing it with European finance, which remains dominated by local banks.

In contrast to Europe there is a rocking dynamism about Wall Street, as evidenced by the speed at which it finances innovation in the real economy. Shortly after leaving OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, two senior executives are separately raising billions in venture-capital funding based on their ideas.

Debt markets are keenly financing new data centres, aiding the boom in AI-related capital expenditure. Both would be unthinkable in Europe, where the biggest financial story is the woes of an Italian bank trying to buy a German one.

Risky business

Rapid change also brings risks. Dangerous financial innovations are often recognised as such only after they falter. Some, like a pandemic-era boom in special-purpose acquisition companies, a method of raising capital, fade into irrelevance without doing much harm. Others, like credit derivatives in the 2000s, wreak systemic havoc. A potent mixture of complexity, leverage and short-term funding is often to blame.

The trouble is identifying cracks. Researchers at the New York Fed and New York University argue in a paper that tight interlinkages between bank and non-bank financial institutions undermine claims that systemic risk has been reduced by regulation since the crisis.

Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, has argued that structural changes in markets are creating new and underappreciated risks, calling out big hedge funds in particular. Harvard’s Jeremy Stein puts it bluntly. “Financial innovation is like a virus, finding weaknesses in existing incentive schemes and regulation,” he says. “When something is growing very fast, that suggests they have found a weakness.”