THE ECONOMIST: The beauty industry is booming as Gen Alpha skin care, male cosmetics and science-backed beauty

THE ECONOMIST: Looking like a trillion bucks? Plain bottles with clinical labels are part of the secret

Consumers across much of the world have been feeling glum lately. In 20 countries tracked by Ipsos, a pollster, sentiment remains stuck below where it was at the start of 2022, before prices rocketed for all manner of goods, followed by interest rates.

Donald Trump’s willingness to tear up global trade and threaten enemies and allies alike with military force has hardly lifted shoppers’ spirits.

Even so, they have never looked more radiant. McKinsey, a consultancy, reckons that retail spending on beauty products worldwide — including skin care, hair care, make-up and fragrances — reached $US440 billion in 2024, having grown by 7 per cent annually over the preceding two years, far outpacing overall retail spending.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Perhaps that reflects consumers’ tendency to splurge on small indulgences during tough times — a pattern Leonard Lauder, an American beauty tycoon, termed the “lipstick effect”.

Stéphane de La Faverie, the boss of Estée Lauder today, points out that people buy its products to help them “feel confident”.

But deeper forces are behind the rise in beauty spending. Consumers glued to social media have never felt more pressure to look good, even more so now as celebrities turn to slimming drugs and advanced plastic surgery.

The result has been a concoction of new customers, products and brands that is propelling the beauty industry to greater heights.

Start with customers. No longer is the industry focused primarily on women of a certain age. Plenty of men now spend lavishly on beauty products, and not just on hair gels and facial creams. The share dabbling in make-up is on the rise, with products that subtly improve appearance, such as tinted moisturisers, concealers and eyebrow gels, most popular.

Beauty retailers such as Sephora are hiring male shop assistants to make their cosmetics counters less forbidding. Male social-media influencers, many from beauty-obsessed South Korea, have helped erode taboos. “If men want to wear make-up, that is now totally okay,” says Priya Venkatesh of Sephora, who oversees its product line-up.

More troubling is demand among youngsters, who are discovering products on social media — from lip glosses to anti-ageing creams — and pestering their parents to buy them.

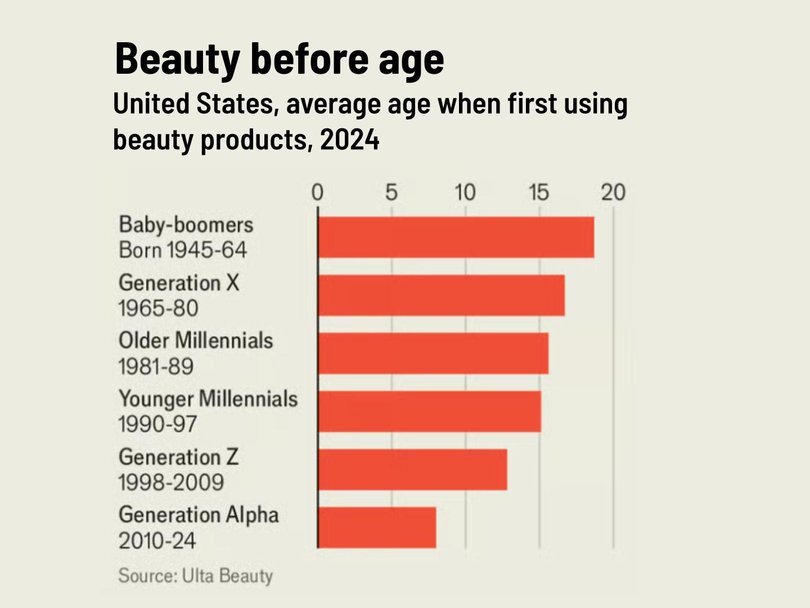

American baby-boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, typically started using beauty products after 18; their generation-alpha grandchildren are getting going at around eight, according to research from Ulta Beauty, another retailer

At the same time, the products consumers want are changing. Take skin care, which accounts for two-fifths of retail spending on beauty. Consumers are learning about the science behind active ingredients such as retinol, which helps with the appearance of ageing, from dermatologists (real and fake) on social media.

Brands such as The Ordinary, founded a decade ago, now offer products with high concentrations of such ingredients at relatively low prices. Pink jars with romantic names are out; plain bottles with clinical labels are in. Supplements such as collagen pills (sometimes called “beauty ingestibles”) and gadgets such as led face masks are on the rise, too.

Men and women alike are also relying more on beauty services, on which they spent nearly $US150 billion ($222b) in 2024, according to McKinsey. These often involve substances and devices that consumers cannot get hold of on their own.

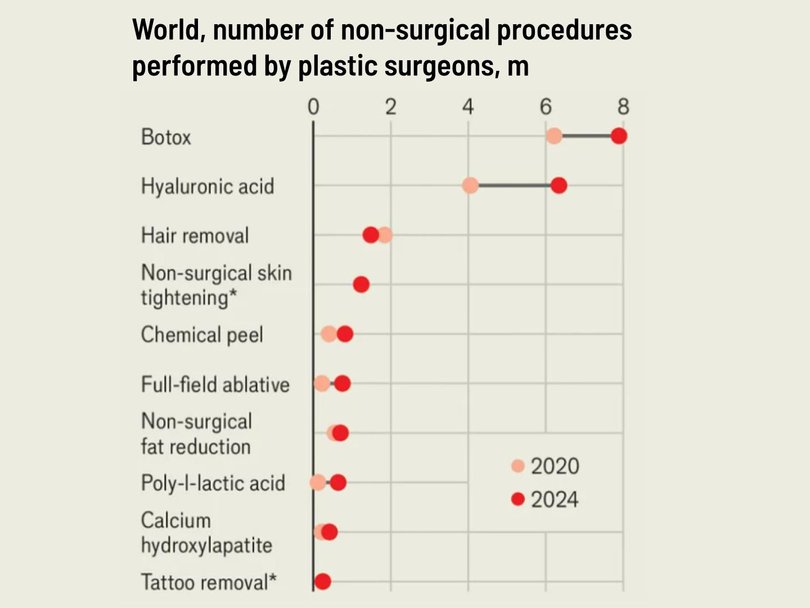

There is botox to smooth skin, hyaluronic fillers to plump it up and chemical peels to brighten it. Lasers can remove hair or thicken it. Plastic surgeons performed over 20m such non-surgical procedures in 2024, up by almost 40 per cent from 2020, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, an industry group (see chart).

Indeed, the line between beauty and medicine has become increasingly blurry. Sarah Chapman, a facialist for celebrities including Gigi Hadid and Victoria Beckham, says her clinic in London has expanded to include dermatologists who write prescriptions and other medical professionals who test clients’ blood and stool to determine the underlying causes of skin troubles. She says clients now come to her wanting to look healthier, not just to get rid of wrinkles and spots.

The focus on new customers and products has often been led by upstart beauty brands. Social media has allowed them to build their businesses without having to spend vast sums on marketing.

Charlotte Tilbury, the eponymous founder of a British make-up brand, notes that her firm’s growth over the past decade or so has been fuelled by social media, describing it as “our biggest shop window”.

Others have followed. Bubble, a skin-care brand founded in 2020, has used social media to amass a teenage following. In fragrances, demand among youngsters has likewise been stoked by newish brands such as Sol de Janeiro, which has rebranded perfumes as “mists”, and kayali, which instructs shoppers to “layer” them (read: buy more).

Many of these upstarts represent not so much a threat as an opportunity for incumbents, which are eager to gobble up buzzy brands that help them grow.

In May e.l.f. Beauty, an American cosmetics company, acquired the make-up brand of Hailey Bieber, wife of Justin, for up to $US1 billion.

Estée Lauder has snapped up The Ordinary, and in June L’Oréal, the world’s biggest beauty business, acquired a majority stake in Medik8, a rival “science-backed” brand.

Last year the French colossus also increased to 20 per cent its stake in Galderma, a Swiss maker of aesthetic injectables and other dermatology products, and said it would buy the beauty division of Kering, a luxury conglomerate. P&G and Unilever, two consumer-products conglomerates with big beauty divisions, have been on their own acquisition sprees.

Scale gives the industry’s largest firms leverage over retailers and the financial firepower needed for splashy marketing campaigns, notes Joël Hazan of Kering.

Under threat in China from homegrown brands such as Proya and Mao Geping, Western incumbents have been investing to consolidate their grip on the American and European markets. They will be hoping that “Instagram Face” — poreless, plump and eerily perfect — does not go out of style soon.

Originally published as Why the beauty industry is booming