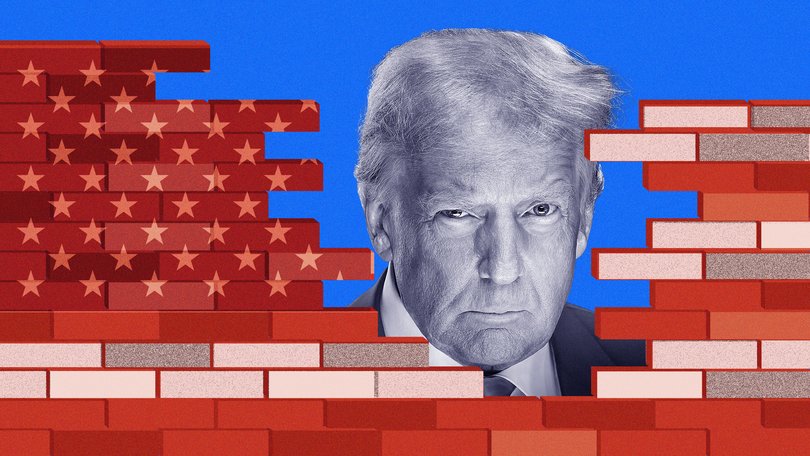

THE ECONOMIST: Zero Migration America as Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown harms the US economy

THE ECONOMIST: Donald Trump’s immigration squeeze is fuelling inflation while starving the country of workers.

Every year since the 1950s, more people have arrived in America than have left. Every year, that is, until quite possibly 2025. Net immigration was over 2.5m a year at the end of Joe Biden’s presidency; this year that figure may fall to zero, or even turn negative.

Donald Trump may have raised tariffs to the levels of the 1930s and be waging war on the Federal Reserve, but it is possible that Zero Migration America will be the most significant of all the president’s economic policies.

Preventing innovators and workers from entering the country not only takes aim at a pillar of America’s success — it does so at a time when the native-born workforce is fast greying.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The Trump administration is pursuing its zero-migration policy with breathtaking vigour. America’s border with Mexico has been in effect closed; barring a handful of white South Africans, few refugees are now granted asylum.

Thus, many fewer people are even attempting to enter the country. “Encounters” at the Mexican border, a measure of illegal migration, have plunged. Meanwhile, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has been told to step up deportation raids.

And although plenty of foreign-bashing politicians differentiate between low- and high-skilled migrants, Mr Trump is going after skilled ones too, with plans to charge $US100,000 ($A150,000) for an H1-B visa, the main entry permit for talented migrants. Attacks on America’s universities are scaring off foreign students and researchers.

Together, such policies represent a revolution in America’s approach to immigration, and one that will have painful consequences. Four of the seven bosses of the Magnificent Seven technology companies were born abroad, for instance, and three entered America through the student and skilled-worker routes that the White House is now targeting.

At the other end of the spectrum, more than half of farmworkers and a quarter of builders in America are migrants, many having arrived illegally.

A smaller population and a slower-growing workforce will reduce the size of America’s economy. That makes a difference: debts will be harder to pay off; a large military, more difficult to maintain.

More worrying, though, is the fact that Zero Migration America will make its residents — native- and foreign-born alike — poorer by pulling down productivity growth and thus GDP per person.

Problems will start to emerge quickly. Plenty of industries rely upon immigrant workers. As migrants stop arriving or are deported, companies will struggle to recruit, since unemployment is already low. That will mean disruptions, lower output and higher costs.

Businesses in San Diego, the big American city most closely linked with Mexico, are “bracing for impact”, says Kenia Zamarripa of the local chamber of commerce. Some report that workers, even those resident in the country legally, have stopped showing up to work when ICE is in town for fear of being rounded up.

Mr Trump has occasionally said that he will shield the worst-hit industries, but it is hard to see how he can without abandoning his migration policies altogether.

Previous crackdowns had a sizeable economic impact despite being less ambitious. According to research by Troup Howard of the University of Utah and co-authors, “Secure Communities”, a deportation push running from 2008 to 2013, raised new house prices by a fifth through starving the construction industry of workers. Closed borders could have a bigger impact, since they will affect more people.

Therefore the coming labour-supply crunch will have macroeconomic implications. From 2022 to 2024, a surge in immigration met demand created by pandemic-era fiscal stimulus. America’s recent “soft landing”, when inflation came down without a recession, would have been much more difficult with closed borders.

Evgeniya Duzhak of the San Francisco branch of the Fed attributes about a fifth of 2023’s fall in the vacancies-to-unemployed ratio — a measure of labour-market tightness — to the volume of new arrivals. Today, lower migration could have the opposite effect: nudging up prices and forcing the Fed to keep monetary policy tighter than it otherwise would have done.

Closed borders will also make life more difficult for central bankers deciding where to set interest rates, as well as anyone else watching the economy. The crash in migration has scrambled America’s data, since the machinery tracking the economy is poorly equipped for sudden population shifts.

Widely watched job-creation figures have cratered, from over 100,000 a month at the start of the year to 30,000 or so. Such numbers could presage a recession if population growth is still strong, or be entirely unremarkable if net migration does indeed end up near zero.

Cutting interest rates too far because of soft jobs numbers that, in reality, reflect falling migration rather than a self-sustaining drop in aggregate demand would be a costly error. So would holding off on necessary rate cuts to avoid making that mistake.

Stephen Miran, a Fed governor recently appointed by Mr Trump, has argued the net effect of lower migration will be lower inflation. That is implausible. The channel he focuses on is housing.

Although he is right that slower population growth will mean less upward pressure on house prices, the migration shock will also pull up the price of new homes by raising building costs. Nor does Mr Miran include the impact of lower immigration on inflation in other industries into his expectations.

These short-term changes will be chaotic, unpleasant, and just about manageable. Companies and policymakers will adapt. Yet closed borders will also have a slower-burning effect. Far more harmful, and tougher to avoid, is the damage to America’s productivity and fiscal health.

Migrants boost productivity by expanding the workforce, allowing both them and natives to specialise. The work that low-skilled migrants do, as cleaners, waiters, meatpackers and so on, lets people in other parts of the economy take on more skilled work.

Florence Jaumotte of the IMF and colleagues find that a one-percentage-point rise in migrants’ share of the adult population ultimately raises GDP per person by 2 per cent in rich countries.

Blocking any sort of migrant from arriving therefore lowers productivity growth. Blocking high-skilled immigration, however, is particularly damaging. Although skilled migrants make up just 5 per cent of America’s workforce, they earn 10 per cent of total labour income.

According to Rebecca Diamond of Harvard University and co-authors, immigrants are responsible for a third of American innovation, calculated using patents, when accounting for their impact on native-born collaborators.

Around 130,000 H1-B visas are granted each year, two-thirds as part of a lottery available to all employers and the remaining third through a route for universities and research bodies. The $US100,000 charge would not apply to people already in the country, muting its effect, notes Jeremy Neufeld of the Institute for Progress, a think-tank.

But the impact on the research route would be brutal: university post-doctorates rarely command the sort of salaries that could justify a $US100,000 visa, even if their work carries big economic benefits. Zornitsa Todorova of Barclays, a bank, estimates that the H1-B charge will shrink the whole visa route by around 30 per cent.

Perhaps the courts will strike down the Trump administration’s visa fee. Yet that is far from guaranteed, and officials may next go after the “Optional Practical Training” route, which most people are on before transferring to an H1-B. Joseph Edlow, head of Citizenship and Immigration Services, said in his Senate confirmation hearing in May that he hopes to stop granting OPT status to foreign students on graduation.

Even if Mr Edlow does not follow through on this intention, concern about the H1-B charge, alongside wider uncertainty about immigration policy, will persuade plenty of brainy foreigners to study elsewhere.

America is closing its borders at an unfortunate time. Without new arrivals, the country’s native-born working-age population would be falling. Public spending is running well ahead of tax revenues, in large part owing to the demands of an ageing population.

The Biden-era immigration wave will shrink the deficit by $US90b ($135b) a year in the next decade, reckons the Congressional Budget Office, America’s budgetary score-keeper. The CBO expects those migrants both to pay more in federal tax than is spent on them by the state, and to boost taxes from other workers by raising productivity. Lower migration will have the opposite effect.

Mr Trump benefited from outrage at uncontrolled immigration under Mr Biden. Now sentiment has swung the other way: 79 per cent of Americans say that immigration is a good thing for the country as a whole, the highest on record.

The problem is that even unpopular Trumpian policies, such as the tariffs introduced during his first term, have a habit of sticking around.

And, if anything, the president seems more inclined to intensify his push for net-zero migration than to cool it. Even if his successor reopens America’s borders in three years’ time, vast damage will have been done.

Originally published as Welcome to Zero Migration America