JOHN McDONALD: Carol Jerrems haunting photographs and a troubled legacy

The renowned Australian photographer’s early death gave her self-destructive behaviour a lurid glamour. But in just one decade she did more than enough to ensure her immortality in Australian art.

Artists who die young often leave an outsized impression. Masaccio, who perished at the age of 26, most probably from the Plague, was the Renaissance genius that barely got started. The decadent Aubrey Beardsley would die of tuberculosis at the same age, while Egon Schiele never made it past 28, his controversial career cut short by the Spanish Flu.

In Australia, the most tragic early departure was painter, Hugh Ramsay, at 28, another casualty of tuberculosis. Next in line must be Carol Jerrems, the subject of a comprehensive survey at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. Jerrems died in 1980, aged only 30, the victim of a cruel liver disease called Budd-Chiari Syndrome, that affects one person in a million.

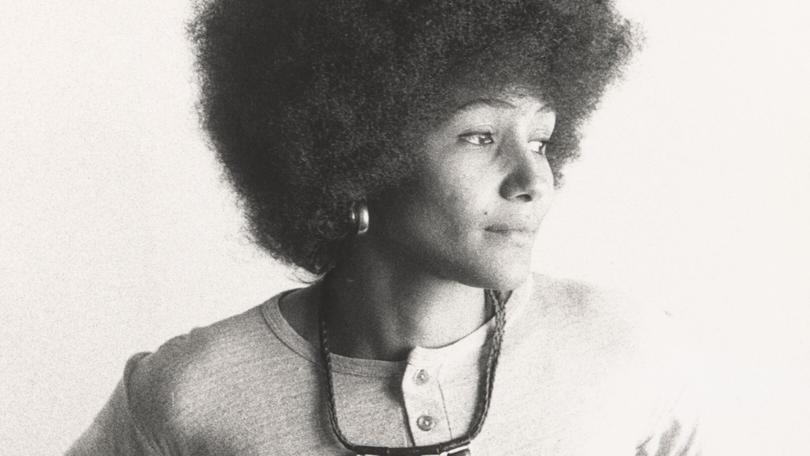

Jerrems is chiefly known for one image, Vale Street (1975), which portrays a young woman and two teenage toughs, all shirtless. To call this picture “iconic” is an understatement – for many commentators it seems to sum up an entire era. The image owes a debt to the sultry presence of the model, Catriona Brown, and its sexual ambiguity. With two males and one woman, it could be a threatening scenario, but Brown seems supremely confident – she’s the leader of the pack, the guys her body guards.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Vale Street speaks to us of the sexual revolution, and the affirmative power of the feminist movement, but it has a je-n’est-quoi which holds our gaze long after we’ve ticked off the themes. The picture, which is both a statement and an enigma, has never lost its power. Released in an edition of nine, it was priced at $45 when first exhibited. Today it holds the auction record for an Australian photograph, selling in 2023 for $171,818.

Over the past 25 years, Jerrems has been the subject of at least three retrospectives, and included in a long line of group exhibitions in which her work has been compared with that of American photographers such as Larry Clark and Nan Goldin. She is not one of those “neglected” female artists we keep hearing about. If anything, she may be over-exposed.

That hasn’t prevented the NPGA from taking another look, in a show touted as the first solely devoted to Jerrem’s portraits. If this isn’t quite the landmark it sounds, it’s because the overwhelming majority of Jerrems’s photos might be classified as portraits. According to a note in the catalogue, the National Gallery of Australia owns 544 contact sheets, of which 487 are “dominated by portraiture.”

Jerrems said, many times, that she cared about people, while genres such as landscape made her feel “cold”. Even when she photographed an interior it would be a portrait-at-one-remove, as in a 1979 shot of her empty hospital bed at the Royal Hobart Hospital. It doesn’t take much imagination to think of the photographer lying in that dismal room which has been personalised by pictures she has stuck on the wall.

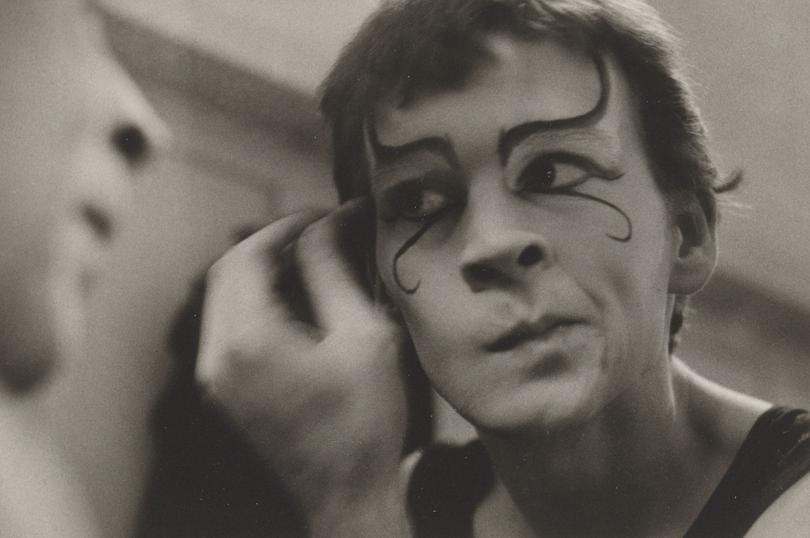

From her early days at Prahran Technical College, where she studied photography with filmmaker, Paul Cox, to her last days in Hobart, Jerrems embraced life with great intensity, taking countless photos of friends, lovers and students. With writer, Virginia Fraser, she published a book on Australian women.

She documented the resurgent Australian film industry, making portraits of her boyfriend, director, Esben Storm, and leading actors. She captured highlights of the popular music scene, from the Skyhooks, to visiting artists such as Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. She snapped the subcultures of the day, and leading Aboriginal activists. In brief, she ticked all the boxes.

For this reason, Jerrems’s work has always been valued as a window onto the counterculture of the 1970s. It has been standard practice to praise Jerrems as a great chronicler of Australian bohemia, but with this show, writes co-curator, Magdalene Keaney, the aim is “to unpack the critical and conceptual dimension of Jerrems’s portraiture.” This vaguely defined project has something to do with social responsibility, egalitarian politics and intimate self-expression.

None of these concepts are unfamilar from the existing literature on Jerrems. By now, every aspect of her work has been so thoroughly picked over that the catalogue writers are left trying to find new ways to say the same things, or simply to speak about their subjective responses to the work.

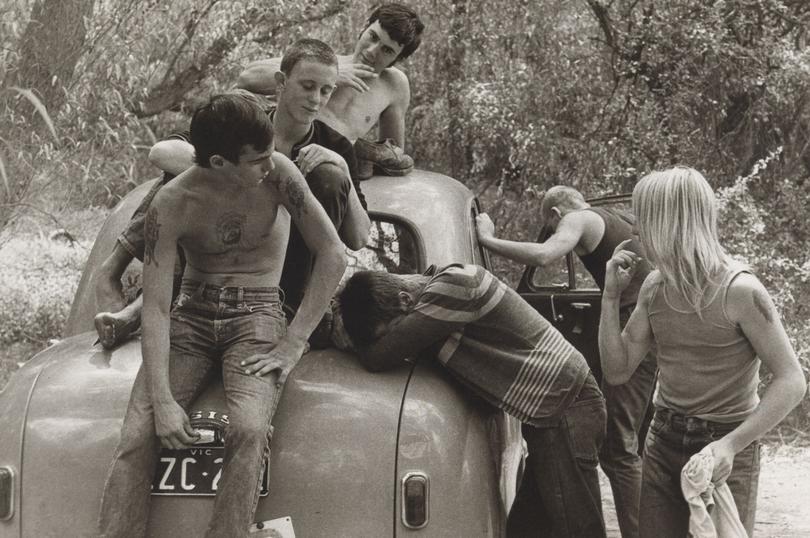

In doing so, they are willing to make huge allowances for Jerrems. She is known to have had sexual relationships with her students when she taught at Heidelberg Technical College, cultivating a group of 15-year-old “sharpies” because she was fascinated by their lives and dress codes. In the catalogue, Rebecca Harkins-Cross writes in relation to the photo, Mark Lean: Rape Game (1975), about the boy’s “raised fist, curled around a bunch of straws, whose length would determine who got to sleep with the photographer.”

The boys, now grown men, told documentary maker, Kathy Drayton, “whatever we suggested she went along with it.” Drayton’s film, Girl in a Mirror (2005) is a sympathetic portrait of Jerrems, but full of disturbing material that shows how far the photographer would go in pursuit of a shot. Friends describe a woman “who loved danger”, who was “always looking for the edge”, but also subject to bouts of crippling depression.

Jerrems’s early death has endowed this self-destructive behaviour with a lurid glamour. Had she lived on and settled into a sober middle age, we may not think so highly of her today. Commentators have been merciless with painters such as Gauguin or Donald Friend for their sexual mores, but Jerrems gets a free pass. I’m not saying we should condemn her, rather that we need to stop judging all artists by our own shifting moral codes.

The main legacy of any artist is their work. Reputation and personal behaviour become less important over time, but the art endures. Some of Jerrems’s images benefited from the intimacy that existed between the photographer and her subject but there are many more that have basic documentary value. We can surmise from her portraits of Esben Storm that she was in love with him, but the bulk of her work details her experiences and the people with whom she mingled in a more workaday manner.

Among Australian photographers no one is more easily romanticised. It’s a fantasy that could never be extended to a figure such as Olive Cotton (1911-2003), who opted out of the art scene, went to live in Cowra, and worked as a commercial photographer. Put Cotton’s best images alongside Jerrems’s and see who emerges on top.

Jerrems’s uniqueness lies in her complete identification with the issues and events of 1970s. Out of this whirlwind came a series of memorable images, of which Vale Street is only the most famous. A portrait of film producer, Lynn Gailey, from 1976, has a similarly mesmeric impact. The light from a window throws a cruciform shadow across the subject’s torso. Her thin arms and body are like vertical streaks of light, her face sculptured and impassive.

A portrait of Evonne Goolagong (1973) shows us the tennis champion as a fresh-faced, open personality. The wall label goes off on a weird tangent wondering if the location is a “domestic setting” or a change room, but nothing could be more irrelevant. It’s Goolagong’s face that dominates, to the exclusion of any fuzzy background details.

There are other striking portraits, some of them lucky snaps, others carefully posed, including images of Judy Morris, the actor who was one of the faces of Australian film in the 1970s. This makes it all the more mysterious that Jerrems’s well-known picture of Morris smoking on the set of In Search of Anna (1977) has been omitted. A tight close-up of Morris’s immaculate features, a fag suspended from her lips, it’s a modern classic.

It might have been good to end the show with a beautiful image, but the curatorial script called for a melancholy finale, with the photos Jerrems took in the hospital, as she grappled with the effects of surgery and medication, becoming gradually resigned to her own demise. As the end approached, she would write in her diary, “it’s no big deal.” In a sense she was right. If this exhibition is any indication, within a decade she had done more than enough to ensure her immortality in Australian art.

Carol Jerrems: Portraits

National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, until 3 March