John McDonald: Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns National Gallery of Australia tour

There are more risks than benefits in consigning pieces by Claude Monet, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, Barnett Newman and Andy Warhol to the bush for years on end.

There are enough works by Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in the National Gallery of Australia to furnish an impressive travelling exhibition, but few would qualify as major pieces. Rauschenberg & Johns – Significant Others, featuring prints and works on paper by these two great American artists, debuted at the NGA in June 2022, before touring to Alice Springs, Ipswich, Cairns, Lake Macquarie, Dubbo, and finally Geelong.

This is precisely the way the NGA should be sharing its holdings, instead of sending off key works on long-term loan.

There are more risks than benefits in consigning pieces by Claude Monet, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, Barnett Newman and Andy Warhol to the bush for years on end. This reckless policy also robs the NGA of many of its biggest attractions and breaks up the landmark display of American art assembled by founding director, James Mollison.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The federal government has funded the Sharing the National Collection program to the tune of $11.8 million, but it would be far better to channel the money into exhibition development. Audiences are more likely to turn up for a busy exhibition program than to view one lonely masterpiece in situ for the next two years.

The Geelong Gallery understands this very well. When I visited the Rauschenberg and Johns show it was supported by three other self-generated exhibitions. Geelong director, Jason Smith, has just been tapped for the job as head of the Art Gallery of South Australia, so one hopes he will continue in the same way.

Robert Rauschenberg died in 2008, aged 82, but Jasper Johns (b. 1930), is still with us. In 2010, his painting, Flag (1958) sold for US$110 million, still the highest price ever paid for a work by a living artist.

When he tried to purchase Johns’s White Flag (1955) for the NGA in the 1970s, Mollison found such records were already on the artist’s mind. Johns told him he wanted to be the first living artist to be paid US $1 million for a work, but the controversy over Pollock’s Blue Poles, which the gallery had bought for AUD $1.3 million, meant the Fraser government would never give permission.

And so we missed out on a seminal painting by Johns, subsequently purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1998 for US$20 million.

By way of compensation the NGA acquired the Kenneth E. Tyler Collection in 1973. It was comprised of the printer’s proofs and associated drawings Tyler had accumulated working with many of the best-known American artists as a master printmaker at Gemini Graphic Editions Ltd. The gallery continued to buy prints until Tyler closed the studio in 2001, with the final total coming to more than 7,400 items.

Almost everything by Rauschenberg and Johns in this exhibition comes from the Tyler Collection. The rather coy subtitle, Significant Others, refers to the fact that the artists were in a relationship from 1953-61.

Over this period, Rauschenberg and Johns formed a private wedge against the Abstract Expressionists, who were the official heroes of the avant-garde. In place of the primal emotions found in the work of Pollock, Rothko and De Kooning, the duo made art that was oblique and impersonal. Rauschenberg had a taste for Dadaist anarchy; Johns, who admired Duchamp, was more coolly intellectual. They had adjacent studios, and “gave each other permission” to do whatever they liked, regardless of presssures to conform.

By the time their liaison ended, Rauschenberg and Johns were no longer artworld outsiders but rising stars. When they commenced working with Ken Tyler – Rauschenberg in 1967, Johns the following year - they were forging highly individual careers.

All the works in this show date from 1967 onwards, even though the title throws a lot of weight on the artists’ formative period. In the digital catalogue, curator, David Greenhalgh, provides a good introduction to Rauschenberg and Johns, and their radical contributions to printmaking, but is a little too eager to see the “queerness” of the art as a reflection of their sexual identity and private connection.

It’s almost too easy to venture such an interpretation. I’m not convinced that “queerness” was anywhere near as important for Rauschenberg or Johns as their relationship to mentors such as Duchamp, and their love-hate responses to the great god, Abstract Expressionism. They may have been discreet about their sexual orientation, as homosexuality was illegal in those days, but that doesn’t mean we need to dwell on their works as cryptic testaments of identity.

Johns has been famously resistant to any reading of his imagery as an emotional testament, although it has regularly been interpreted in both public and private terms. One crucial picture is In Memory of My Feelings - Frank O’Hara (1961), which refers to the best-known poem of a close friend. This grey painting is as ambiguous as O’Hara’s verses, but it carries an undeniable emotional charge. It feels sad, bitter, grief-stricken, but provides no reasons.

Johns’s reticence to reveal his subject matter is a reminder that he takes his privacy seriously and believes a work of art must stand or fall on its own terms, without excuses or explanations.

One finds the same attitude in many artists who have no wish to have their work viewed in terms of their gender, race, or sexual preferences. The danger in categorising artists as “queer” is that it ultimately narrows the avenues of interpretion. It’s a modish, over-used term of scant art historical value.

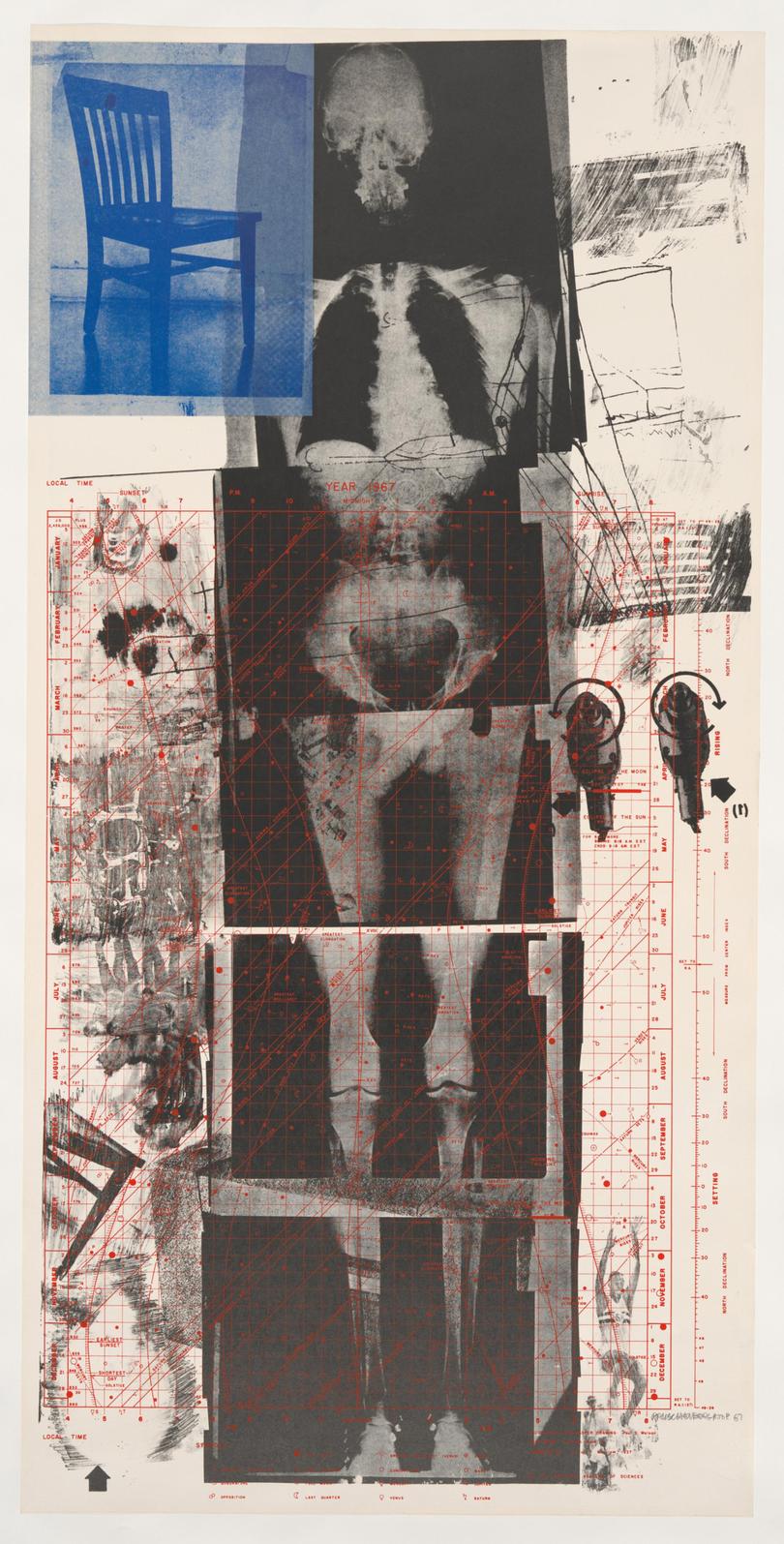

When we get past this small hurdle, there’s a lot to appreciate in the Geelong exhibition, starting with Rauschenberg’s Booster (1967), a life-sized, lithographic self-portrait made from six X-rays of the artist’s body. The figure is surrounded by small images of car crashes, reflecting a time when everything was going wrong in Rauschenberg’s life. His solution was to consult an astrologer, which led to a network of thin, red lines from star charts spread across the print.

As a first venture with Tyler, it’s an ambitious undertaking, consistent with Rauschenberg’s lifelong reputation as a risk-taker. Equally startling is Cardbird Door (1971), part of a series in which the artist faithfully reproduced details of discarded cardboard packaging, demonstrating the magical power of art to turn rubbish into gold. In this piece he has used the prints as part of a “combo”, assembling them into a sculptured door.

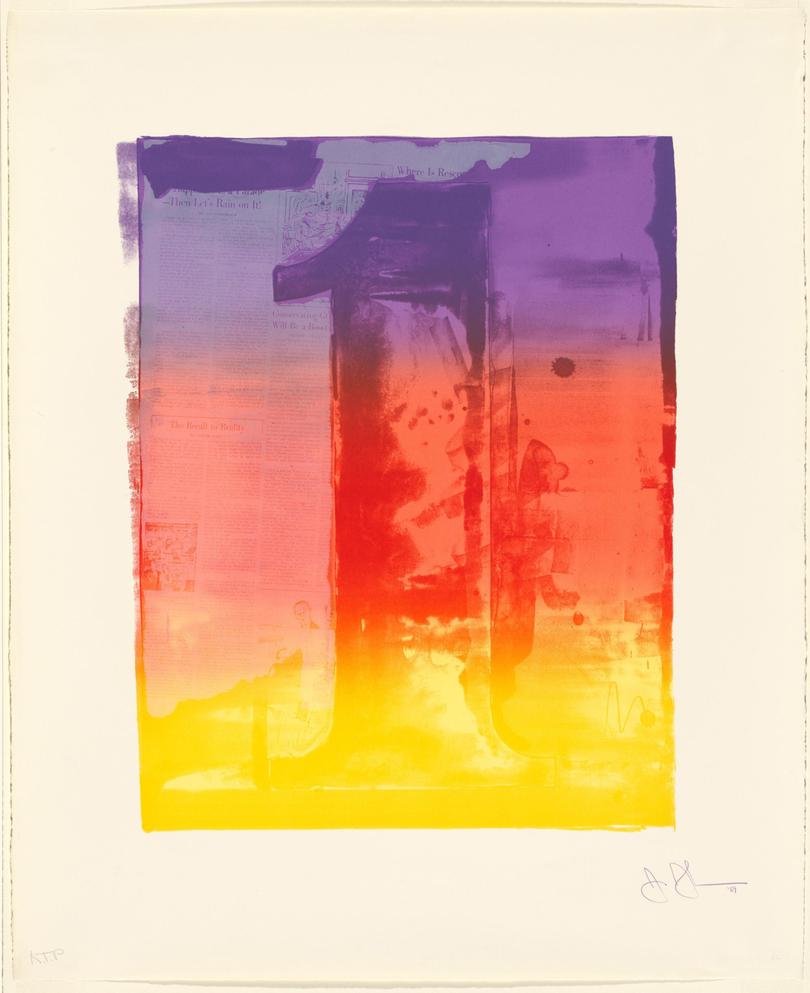

Johns is no less of an innovator, although for him, printmaking is often an extension of painting, taking the same imagery into a dfferent medium. Where Rauschenberg is spontaneous, Johns is calculating, preferring to refine his ideas rather than move into virgin territory. In 1959 he produced a painting called Periscope (Hart Crane), in shades of grey, but with three panels labelled “Red”, “Yellow”, “Blue”. A print of his own hand reaches out of a circle at the side – a reference to the poet, Hart Crane, who committed suicide by jumping from a ship in the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1979, Johns reprised the image as a print with Tyler, but now the panels correspond to the nominated colours. Presumably this more vibrant version, twenty years on, reflects a more cheerful, confident state of mind. Not drowning but waving?

Johns’s The Critic Smiles (1969) is a relief print made from lead, tin and gold, based on an image from 1966, created as a riposte to a negative review from critic, Hilton Kramer. A set of gold teeth attached to a toothbrush, it’s a bizarre, unsettling work that suggests gold teeth retrieved from the bodies of dead artists, and the critic as a kind of aesthetic hygienist, bent on eliminating decay and impurity.

Although he may have been privately outraged by Kramer’s critique, Johns chose a very public vehicle for his revenge. Nowadays, the article has been forgotten but the image has been viewed by millions. In the later, ‘colder’ version, the leaden backdrop implies the critic’s leaden thoughts or prose.

Kramer may have taken some solace from the elaborate nature of Johns’s response, as it reveals the importance assigned to art criticism in New York in the 1960s, a time when modernism was still spawning new movements. Whatever feelings or secrets Rauschenberg and Johns were concealing in those early days, they understood the need to create original, challenging images that arrived with explosive impact.

As printmakers, they would find a willing collaborator in Ken Tyler. It’s thanks to Gemini G.E.L. that we in Australia can enjoy a comprehensive overview of these artists, while still lamenting the iconic painting that got away.

Rauschenberg & Johns – Significant Others

Geelong Gallery, until 9 February 2025

John McDonald travelled to Geelong, courtesy of the Geelong Gallery.