Big Brother Australia 2025: Can once-groundbreaking reality TV show be anything more than a cultural artefact?

Twenty-four years ago, voyeurism in itself was a compelling, singular selling point. Now, it’s just normal life. Can Big Brother’s return actually work?

It was a familiar voice that last night asked, “Are you ready to come home?”

The voiceover belonged to Mike Goldman, better known as the narrator of Big Brother Australia on both its original Channel 10 run and the Channel 9 revival.

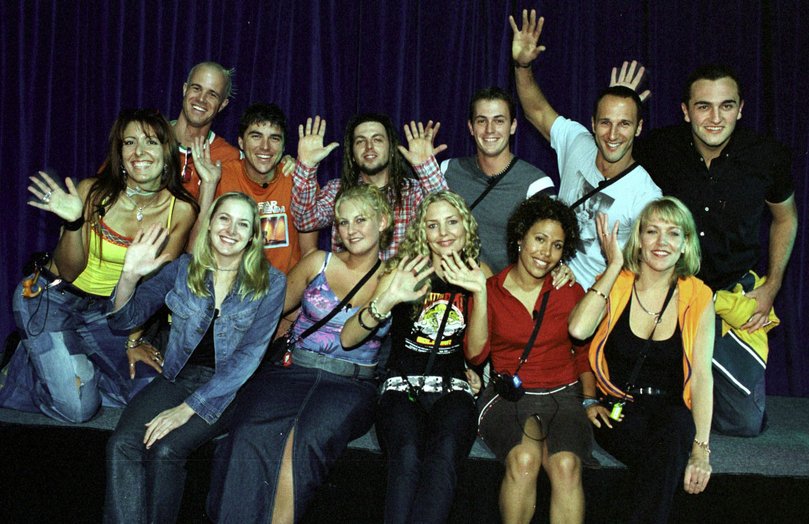

With that one line, the new iteration of Big Brother declared its intentions very clearly. This is supposed to be a return to the series as it was, when it was a pop cultural sensation in the early 2000s, when the show introduced the country to the likes of Chrissie Swan, Sara-Marie’s bunny dance, the dancing doona and the infamous turkey slap.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.For a moment in time, Big Brother loomed large in the culture, a chance for everyday TV viewers to tune in for a nightly dose of permitted voyeurism, and get a glimpse of how people behave when they forget they’re being filmed and broadcast to the world.

But can you ever really go home again?

Big Brother launched in Australia in 2001, not long after the format had debuted in the Netherlands, and it took its name from the pernicious, totalitarian figurehead in George Orwell’s seminal novel 1984.

It wasn’t the first global reality TV series in which the whole point was to watch strangers be bored – MTV’s The Real World had been going since 1992 – but it was the first to take off in a massive way in the mainstream.

The idea was that Big Brother was always watching and he could dictate what did and didn’t happen in the house, whether it was limited to bare rations for food or being rewarded with a random party.

The contestants weren’t in control of their lives, and their fates were decided by the voting public, effectively an extension of Big Brother, who threw their support – and the money it cost to vote – behind people based on what they judged of these strangers just living a version of their lives.

It’s instructive that the first two winners of Big Brother Australia, Ben Williams and Ben Corbett, were affable, average and, this is no jibe, unmemorable white guys who largely sailed under the radar.

In those earlier years, contestants regularly reported they would genuinely forget the cameras were there, and carried on as if they were in their own version of the first act of The Truman Show.

It did change over time as media consumption shifted and audiences demanded more drama, and those with bigger personalities had a better sense of how shows were produced and edited, and how to make those cameras work for them and their celebrity ambitions.

Compare the two Bens to someone like 2013 winner Tim Dormer, who made being entertaining a strategy and stirring up trouble a tactic. A decade earlier, Dormer would’ve been one of the first to be voted off, but by his year, social media had changed everything.

When Big Brother launched in 2001, only 21 per cent of Australians had accessed the internet at home, according to the census. The proto-social media platforms at the time were instant messaging, such as ICQ and MSN Messenger or early blogs such as LiveJournal.

MySpace debuted in 2003. Facebook launched in 2004, but was originally limited to elite universities in America before it was made publicly available to all in 2006. YouTube came along in 2005, Twitter in 2005, Instagram in 2010, Twitch in 2011, OnlyFans in 2016 and TikTok globally in 2018.

Reality TV shows, which spawned personalities such as Kim Kardashian and Bethany Frankel, and the plethora of social media platforms that made superstars out of MrBeast and Druski changed the rubric – the value of a person was not their character but how much they entertained you.

The attention economy is almost like an inversion of what French philosopher Michel Foucault, in expanding on Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison design, had theorised in terms of being watched would lead to self-surveillance and social policing on a wider scale.

It’s a model that doesn’t reward understatement and moderation, it’s about being noticed and strident.

Which is why there’s a disconnect when Channel 10 says this 2025 version of Big Brother is about getting back to the show it was. In the press release announcing its return, it touted that in addition to capturing a new generation of fans, it wanted to “rekindle nostalgia for long-time viewers”.

Nothing wrong with having those ambitions, but it’s a hard hill to climb.

Everyone, especially those younger generations who grew up on social media, they can watch almost whoever they want on whichever platform whenever they want, and nostalgia is thorny when mindsets have altered so dramatically.

In a world where hundreds of millions of people live their lives online, broadcasting every inconsequential detail, there’s nothing special about a dozen and a half people nattering about how to cook tinned lentils or not having access to make-up remover.

Even if the producers have among its cast certain 2025 archetypes, including one young woman who, at the first opportunity, plugged the designer she was wearing (#sponcon?) and one young man who, with his proclamations about antiquated gender roles, seems to have walked straight out of the manosphere.

The promise was “real people”, and as much you actually had some in those early years of Big Brother, anyone who self-selects to audition for a reality TV show in 2025, knowing full well the social media component that comes with it, is, arguably, not going to be a “normie”.

And unlike other current reality TV shows such as Married At First Sight, Big Brother doesn’t really have an organising structure with a clear narrative arc that contestants are purportedly working towards (a date, a renovated house, plating the perfect gnocchi).

Voyeurism in itself is no longer a compelling or unique selling point, that’s just normal life.

There are enough real-life totalitarian rulers in the news. Car crash media personalities are everywhere. If you really want to watch someone boil tinned lentils, there are probably 7025 different feeds for that.

Plus, everything we do online and much of what we do offline is being watched and tracked (cookies, phone cameras, CCTV, doorbell cams), sold to and sold off.

Last night’s first episode drew 1.48 million viewers nationally, but it’s incomparable to all previous seasons because how TV ratings are measured changed significantly in 2024.

Rival reality programs My Kitchen Rules and The Golden Bachelor last night pulled in 1.91 million and 1.89 million, respectively.

Still, it’s a good result as Channel 10 has not on a Sunday cracked the million mark in the past month, and according to the network, it’s a 114 per cent uptick year-on-year.

Who knows, maybe Big Brother 2025 will be a huge, or even moderate success, no one begrudges the producers that.

But in the social media age, can Big Brother be anything more than a cultural artefact?