Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam explores the multitudes of con-artist Lou Pearlman

Like a first-year philosophy student’s essay on epistemology, truth can be a malleable and increasingly confusing concept. What is true, who gets to define it, and is there even such a thing as an objective truth?

There’s been a lot of talk in recent years of “my truth” and “post-truth” but, really, the more useful framework is to acknowledge that two seemingly contradictory facts can both be true. This is what people mean when they say you can hold two truths in one hand, because human beings are multifaceted and weird.

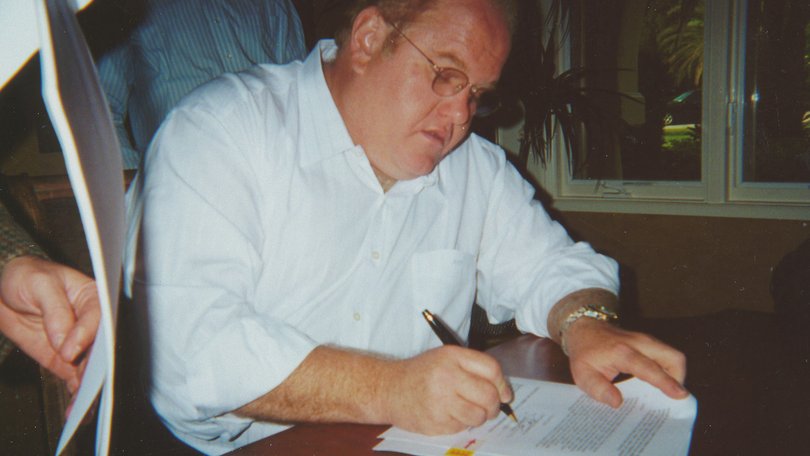

It’s true that Lou Pearlman was a con-man who ran a decades-long ponzi scheme that dudded scores of victims out of their life savings to the tune of $US500 million.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It’s true that Pearlman was one of the most influential forces in pop music in the 1990s, and made the Backstreet Boys and *NSync into global superstars.

It’s also true that most of the bands he managed, including his two most famous clients, ended up suing him for misrepresentation and fraud.

The connection between Pearlman’s stratospheric entertainment success and his ponzi scheme was inextricable. One would not have happened without the other – and those are two truths explored in the three-part Netflix docuseries Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam, which is released on Wednesday.

Pearlman was the only child of a Jewish couple – and a first cousin to Art Garfunkel – who had aspirations bigger than his parents’ one-bedroom apartment in New York, where he had the bedroom while his folks slept on the sofa-bed in the lounge.

While running businesses involving blimps and loaning out private jets – or so he claimed – Pearlman said he noticed an obsessive fever among young girls for New Kids on the Block. He wanted in.

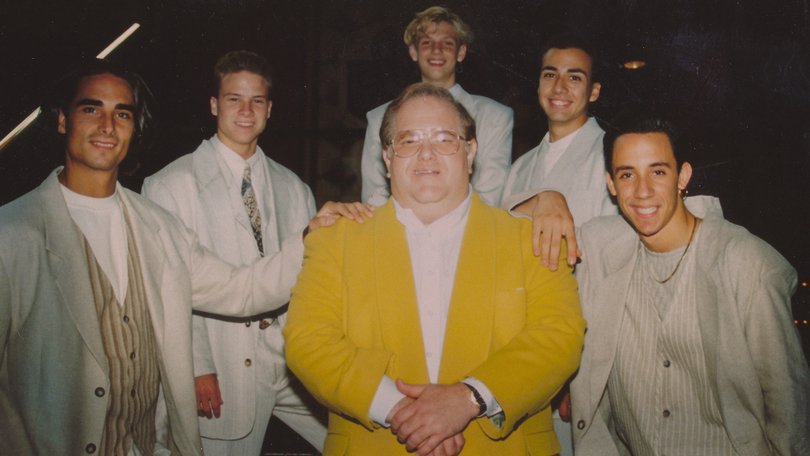

He put out an ad in the paper in Orlando, Florida, calling for teen boys to audition for a music act. AJ McLean was the first person to make the cut, then Nick Carter, Brian Littrell, Howie Dorough and Kevin Richardson.

Pearlman had a showman’s instinct and he shaped the five boys into a band, first propelling them to fame in Germany and then in the US where, as he saw with NKOTB, mobs of young girls screamed for their idols.

It was tough work. BSB would rehearse in Pearlman’s un-airconditioned blimp hangar, they toured American schools, they went back and forth between the US and Europe. And for their troubles, despite going platinum and selling out stadiums, they were cut a cheque for $US300,000 for years of work.

Pearlman, meanwhile, was luxuriating in a waterside mansion.

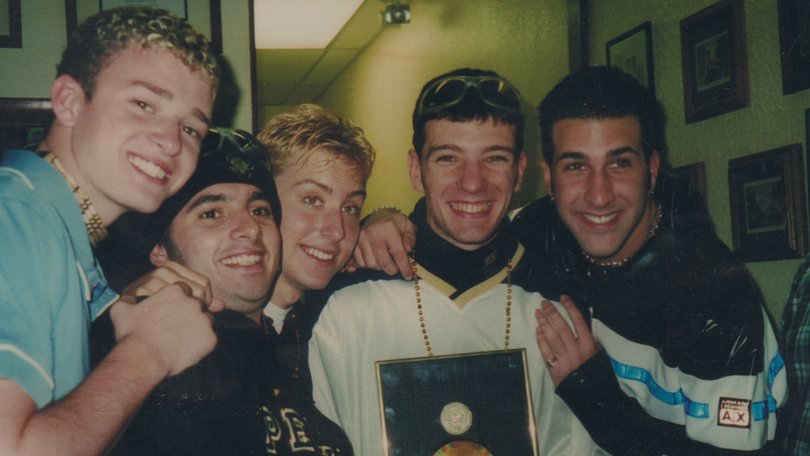

As he wrote in his bio, if BSB was Coca-Cola, then someone was going to come along and invent Pepsi, and it may as well be him. He met Chris Kirkpatrick, who went on to form *NSync with Justin Timberlake, JC Chasez, Joey Fatone and Lance Bass. The boys saw what Pearlman did with BSB and signed on.

When you’re young and hungry and someone comes along and promises you the world, you’re not going to pass up your shot.

Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam is so named because Pearlman used the money he raised through his ponzi scheme (and there was no one he didn’t take money from, including the elderly parents of his best friends) to finance the development of the boy bands. In turn, he sheathed himself in the success of BSB and *NSync to woo would-be investors to his fund.

The band members recalled they were often called on to sing in front of random people and “friends” of Pearlman’s. How could anyone who could put a Backstreet Boy in front of you and have him launch into a personal serenade be dodgy?

Would BSB and *NSync be the pop powerhouses they were without Pearlman? Probably not. He had an indelible impact on music, even if his later forays into the space (Natural, O-Town, LFO, Innosense) were less memorable. But he knew how to build and market, or in some cases, just market.

Those same instincts is what convinced so many people to sink their money into what he was selling. And, ultimately, the house of cards collapsed as prosecutors and law enforcement’s dragnet closed in.

In the docuseries, directed by David Terry Fine, the pieces-to-camera from the likes of Kirkpatrick, McLean and Dorough are conflicted, some more strident about Pearlman’s exploitation than others.

There are also testimonials from his victims and from his friends, some of whom are still loyal to a man long dead. Michael Johnson, a former member of Natural, recounts a man who screwed him over but who he still considered to have been his best friend.

If there’s one thing to take away from Dirty Pop, it’s that it’s difficult to reconcile truths that seemingly shouldn’t be able to sit together. Sometimes, there’s no way to work through it and arrive at one conclusion.

When Pearlman died in prison in 2016, Jacob Underwood from O-Town posted on social media, “Hard to describe what I’m feeling. He was always nice to me, even when he was stealing from me”.

Within that message contains the multitudes of Pearlman’s impact. He did good things. He did terrible things. Both things are true.

Dirty Pop: The Boy Band Scam is on Netflix from July 24