Say Nothing and the best TV shows and movies about The Troubles

A new drama series delves into the history of The Troubles through the stories of the violent revolutionary Price sisters. It continues a rich legacy of the conflict on screen.

At most points in recorded history, somewhere in the world, sectarian violence flared. Communities torn apart by religion and centuries-old divisions today share a trauma of oppression, violence and blood of those beset by similar legacies.

That’s cold comfort to those suffering through current conflicts, but maybe there is something to be taken from the fact that sometimes, those fights end, or at least live with a sort-of amnesty. The scars never quite heal but fresh wounds are fewer with each passing moment.

For three decades, Northern Ireland was locked in intense political conflict between the British loyalists and the Irish revolutionaries, battling over a question of nationhood. Known as The Troubles, it notionally started in the late 1960s and ended with the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.When you have two strongly opposing sides and a brutal body count, art is one of the ways to try and make some sense of the war, especially one that is so emotionally charged, contested and tangled.

Say Nothing was based on Patrick Radden Keefe’s acclaimed 2018 book and tells two parallel and connected stories — one of the Price sisters who joined the IRA as young women and became involved in some key moments in the movement, and of Jean McConville, a single mother-of-10 who was murdered in 1972.

The series spans decades and it is a punchy, visceral and meticulously crafted historical drama that drops you right into the jeopardy, rage and high stakes of the story.

Dolours Price (Lola Pettigrew as the young version and Maxine Peake as the older woman) and her sister Marian (Hazel Doupe and Helen Behan) were born in Belfast to staunchly republican and activist parents.

They became involved in the IRA after the two were viciously attacked by Ulster loyalists during a peaceful march from Belfast to Derry in which the republican participants refused to fight back. The Burntollet Bridge would be remembered as a pivotal event that tipped the two sides into The Troubles.

The violence and hatred from the loyalists, as well as the idling and complicity of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, radicalised many republicans including the Price sisters, and they retaliated with riots in Derry city.

The Prices would go on to be involved in the 1973 bombing of the Old Bailey in London, take part in prison hunger strikes and in McConville’s death.

The cost of political violence touches everyone, including those inflicting it as they grapple with the morality of destruction and death in the name of a justified cause. Say Nothing takes this question very seriously and it is one of the show’s strengths.

The Troubles may have ended a quarter of a decade ago but it is still in recent memory. Many of the combatants are still alive, as are the traumas of those who survived it.

That’s all the more reason to contend with historical memory and confront the legacy of British colonialism and the violent response to it.

The filmmakers of Say Nothing have said they were surprised the notoriously risk-averse Hollywood was willing to even take the project on, but the show is not the first screen project about The Troubles. Here are some others to consider once you’re done with Say Nothing.

HUNGER

British visual artist turned filmmaker Steve McQueen made his feature debut with Hunger, which was also Michael Fassbender’s break-out role. Fassbender plays Bobby Sands, who died after a 66-day hunger strike fighting for recognition as a political prisoner, which the British would not grant.

The movie is intense and distressing, and the signature scene between Sands and a priest (Liam Cunningham) remains one of the most engrossing two-handers in 21st century cinema.

BELFAST

Kenneth Branagh’s personal ode to his childhood and a city on the verge of all-out conflict, this semi-autobiographical film balances nostalgia and the rose-tint of a kid’s memory with the reality of the situation.

The film is set in 1969 and young Buddy’s home is surrounded by tanks and barricades as Protestant rioters target the Catholic families on the street. The story is centred on Buddy’s parents trying to figure what home really means if it’s no longer a place you recognise.

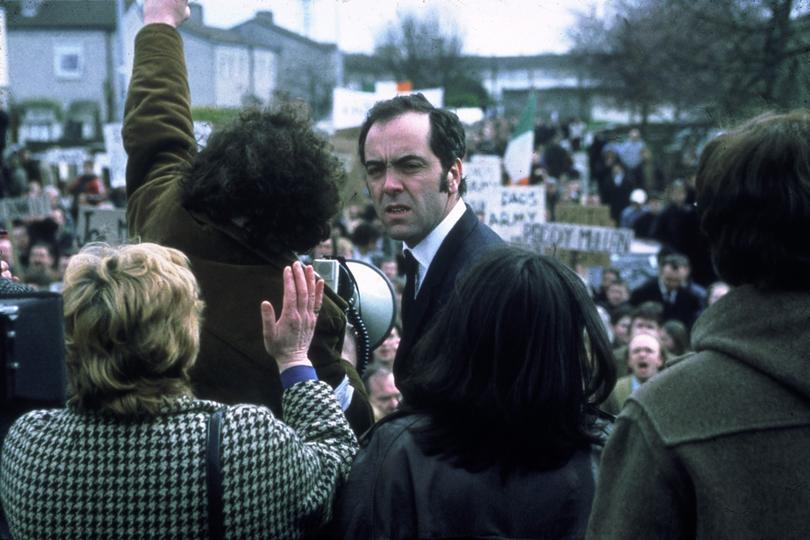

BLOODY SUNDAY

Paul Greengrass’s 2002 movie depicts the brutal events of the 1972 civil rights march through Derry which ended with British Army troops firing on the unarmed protestors, killing 14 people. A pivotal moment in history, it’s also one of the most dastardly.

James Nesbitt plays Ivan Cooper, a politician who organised the march. Like many of Greengrass’ later work, his use of handheld cameras elevates suspense and force in an already chaotic situation.

DERRY GIRLS

One of the best shows of the past decade, Derry Girls showcases the experience of The Troubles through teenage girls growing up in Derry in mid-1990s. It may be part of the stories, memories and day-to-day of their lives and their families, but they are also young women trying to have fun, grow up and discover themselves. Blending humour, pathos and a lot of sass, it’s fantastic. It also has one of the best finales that’s guaranteed to make you weep.

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

One of the great dramas about injustice and the way the legal system can be weaponised against an innocent man, In the Name of the Father is a powerful condemnation of the trial of the Guildford Four.

Daniel Day-Lewis plays Gerry Conlon, a man who is wrongfully accused of bombing a pub in 1974. Director Jim Sheridan’s film pulses with rage.

71

On the surface, 71 is a non-political action thriller, following a young British soldier who is sent to Belfast during a riot and is separated from his unit and lost behind “enemy” lines.

But the anarchy and violence from both sides, and all the young foot soldiers caught in the middle, makes a cogent argument of its own – no one wins in this. It stars Jack O’Connell in the lead but features a swathe of then young-and-comers including Barry Keoghan, Jack Lowden and Sam Reid.

KNEECAP

Kneecap does not technically take place during The Troubles but it explores the power imbalance that still exists in Northern Ireland.

The fictionalised origin story of Irish rap group Kneecap, who play versions of themselves, is a kinetic and confident film which looks at oppression through controlling language and youthful rebellion. The Irish-language film is Ireland’s entry to the next Oscars in the international feature category.