JOHN McDONALD: Adelaide’s Radical Textiles exhibition often mistakes personal identity for political message

JOHN MCDONALD: Radical Textiles examines the way textiles have been used to convey political messages. Unfortunately, it often leans heavily on the identity of the artist to supply this ‘political’ dimension.

Earlier this year I saw an exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery in London, called Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. That title proved alarmingly accurate because almost a third of the exhibits had been withdrawn, after the Barbican banned a speaker at a London Review of Books seminar from reading a paper comparing the Holocaust to the carnage in Gaza.

The show, which had nothing to do with this badly organised forum, was collateral damage. To protest this alleged offence against freedom of speech, the politically charged participants in a politically charged exhibition, took their ball and went home.

I’m assured by the curators of Radical Textiles at the Art Gallery of South Australia, their exhibition bears no resemblance to Unravel. Where the Barbican concentrated on works of contemporary art employing textiles, the local show is more broad-ranging, including historical items such as a 1900-02 tapestry by William Morris & Co. and an extraordinary “crazy quilt” created by settler seamstress, Rebecca King, between 1890-95. There’s also a heroic display of trade union banners, emphasising what a truly radical place South Australia once was in comparison to the other colonies and indeed, the rest of the world.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.In Radical Textiles, Rebecca Evans and Leigh Robb have put together a show that looks at the way textiles have been used to convey political messages, to express solidarity, to provide consolation for those who are marginalised or oppressed. It’s an anarchic collection that leans heavily on the identity of the artist to supply the “political” dimension. It seems to be taken for granted that all pieces by First Nations artists are inherently political, as are all works by “queer” artists. Yet there’s a chasm that separates a trade union banner from some of the more lightweight, campy items.

In the catalogue one learns about South Australia’s long list of firsts. It was the first of the colonies to adopt the eight-hour day, in 1873; first to legalise trade unions, in 1876; first to give women the vote, in 1894; and the first state to decriminalise homosexuality, in 1975.

It may have something to do with the fact that South Australia was the only colony not founded with convict labour, but it was well in advance of its eastern counterparts when it came to human rights and freedoms.

The progressive politics didn’t translate into cutting-edge aesthetics, as the ceremonial banners for the Builders’ Laborers’ Union (1910), and the Australian Society of Engineers (1912), are suitably laborious, with allegorical figures, coats of arms, native flora and fauna, and all the instruments of the trade crammed into large, squarish pictures which were carried through the streets on Labour Day. One appreciates the succinctness of another banner which simply reads: No Surrender, in silver letters on red.

Those Edwardian Builders’ Laborers would have been surprised by some of the sacred relics of the 1970s and ‘80s, preserved by the Adelaide Women’s Liberation Archive, such as a well-worn yellow T-shirt screenprinted with the words: “I Am a Lesbian”. There’s not a lot of artistry but the message comes across loud and clear.

This exhibition allows us to chart the evolution of left-wing politics from its traditional concerns with workers’ rights, through women’s liberation, gay liberation, and Indigenous rights. All these movements were well-defined in their day, but nowadays confusion reigns. Take the word “queer”. Although the term is used carelessly as a synonym for “homosexual”, it carries a supplementary weight of meaning. To be textbook “queer” is to be proudly glued to society’s margins, opposed to all the orthodox institutions of late capitalism and the nuclear family, in a state of perpetual revolt.

The gay American journalist, James Kirchick, has pointed out that Queer activists in the USA have been savage in their denunciation of Pete Buttigieg, the outgoing Secretary of Transportation, for being “a straight politician in a gay man’s body.” Happily married, with kids, Buttigieg is viewed as having sold out to a system that needs to be opposed at every point. The idea that one might be gay but not at war with society, is anathema to hard-core Queer politics, which rejects the mainstream, and those gay men, lesbians and feminists who have found a place within it.

What would today’s more extreme activists have made of former SA Premier, Don Dunstan, whose famous pair of pink shorts worn to Parliament one day in 1972, are featured in this show? Dunstan is hailed in the catalogue as a “queer” icon, but he was as much a party politician as Buttigieg. Should we remember him for his shorts rather than his long years as part of the Labor machine?

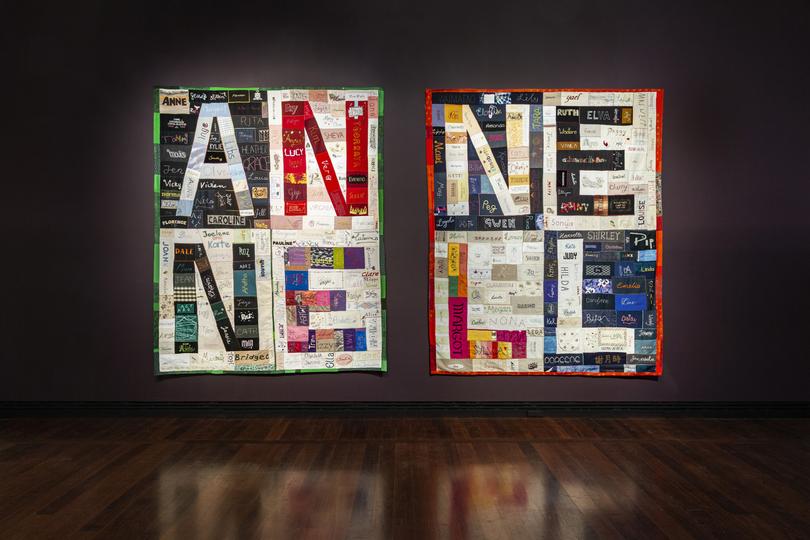

When we look at the quilts made in tribute to those who died of AIDS, they can be touching, idiosyncratic and funny. They are records of human lives and shared human tragedies, not strident statements of social division.

We’ve seen the results of the new oppositional mindset in an American election in which macho swagger, misogyny, racism and homophobia won an overwhelming vote of confidence from the electorate. The counterproductive posturing of today’s radical fringe threatens to undo two generations of gains made by their predecessors. They may, however, be satisfied that Donald Trump will give them so much to oppose.

In this sense, the social justice components of Radical Textiles, feel strangely disjointed. One can see the direct political relevance of the trade union banners, or the public artworks of veteran feminist, Kay Lawrence, most especially her two tapestries, Equal Before the Law and Votes for Women, which have hung in the Chamber of the South Australian Parliament since 1994.

It’s less obvious in what way many of the gaudy dresses made by contemporary designers contribute to a progressive stance. Whatever the supposed “subversive” credentials of designers from Linda Jackson to Jordan Gogos, it’s hard to accept that extravagant, over-the-top frocks constitute a significant political statement. In the past, you achieved a political profile because of the things you made, today it’s through who you are, as if your ethnicity or sexual preferences were enough to send tremors through the capitalist system. In fact, most of these people are capitalists themselves, selling a product not to the masses, but to the wealthy fashionistas and cultural institutions.

As high art or fashion, it’s hard to love this over-the-top, over-hyped product, especially in comparison with a room hung with tapestries designed by Sonia Delaunay, Alexander Calder and Le Corbusier — most of them borrowed from Naomi Milgrom’s collection. The crisp forms and simple planes of colour in these works are instantly attractive, although their ‘radicality’ is purely formal.

Then there are the grotesques – Eko Nugroho’s embroidered cartoon figures; Tarryn Gill’s Guardians (2014-16), with their demonic faces and muttering voices; and Fiona Hall’s installation, All the King’s Men (2014-15), consisting of two rows of dangling heads, made from shredded army fatigues. These eye-catching works portray contemporary life as a horror movie filled with violence and lurking evil. If Nugroho’s characters have a playful dimension, Gill’s monsters are more unsettling, while Hall has created a virtual cannibal wasteland.

It’s odd to find All the King’s Men exhibited alongside the late Liz Williamson’s Weaving Eucalyptus Project (2020-22), which consists of 100 woven silk panels, dyed with the natural colours of eucalypts from around the world. This serene homage to nature is the complete antithesis of Hall’s morbid vision.

Perhaps such contradictions are the whole point of this show. The sheer variety, with its blend of social justice and aesthetics, its famous and obscure artists, its mixture of large public statements and small intimate objects, leaves us in the dark as to how the curators define “radical”. At one turn it’s a purely formal thing, at another it’s a grass-roots political commitment. The word can describe a dark reflection on human nature, or a celebration of shared identity. By the end, the display has become a free-for-all, as if the most radical thing we could do would be to put on some extravagant outfit and go partying. It’s no longer the workers of the world who are the target audience, it’s the hipster who believes that politics consists, first and foremost, in the liberation of one’s own desires.

Radical Textiles

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide

Until 30 March 2025

John McDonald flew to Adelaide with assistance from the AGSA