JOHN McDONALD: National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition Cats and Dogs in Design an unprovoking crowd pleaser

JOHN McDONALD: A national gallery’s new exhibition finds the art museum making an unusually realistic assessment of what the public wants. For better or worse, that’s cats and dogs.

Cats and Dogs may sound like a frivolous idea for an exhibition, but the National Gallery of Victoria has earned the right to a little frivolity. Over the past decade the NGV has been so far ahead of its peers in its professionalism and the quality of its exhibitions, that it would be churlish to say it has no right to host an inexpensive, collection-based crowdpleaser.

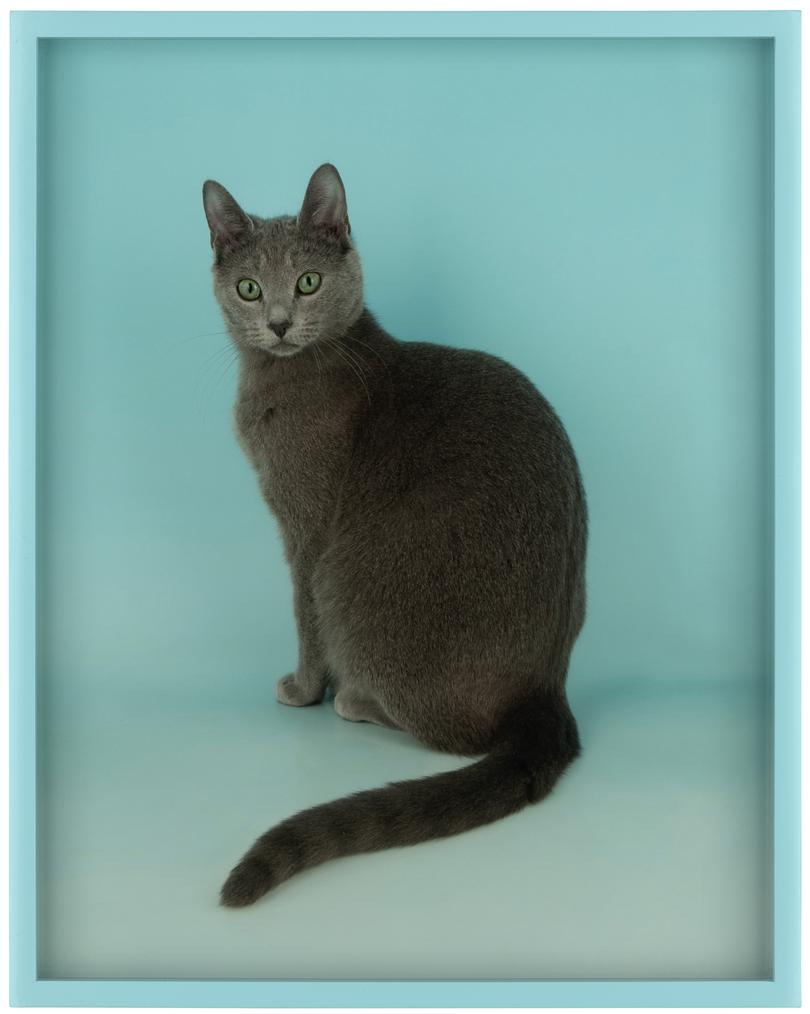

In Cats and Dogs in Art & Design, curators, Laurie Benson (cats) and Imogen Mallia-Valjan (dogs), have put together a broad-ranging survey that showcases the depth and variety of the permanent collection. Whereas most collection shows are no more than gap fillers, in this instance there’s a catalogue, merchandise, and even an interactive program that invites viewers to post images of their own pets. Perhaps the ultimate mark of confidence is that this is a paid show, with a price tag of $16 for an adult ticket.

Cats and Dogs finds the art museum making an unusually realistic assessment of what the public wants. It’s commonplace that the economy has never fully recovered from the effects of the pandemic, but the same can be said about the cultural economy. During the lockdowns museum professionals had a lot of time to think about what they should be doing to bring back audiences as quickly as possible. Instead, they became preoccupied with politically correct protocol – Indigenous “nations” on wall labels, nominated pronouns on official documents, Gender Action Plans, and on and on. These things may be “right” in some absolute sense. They may have made museum staff feel virtuous and morally pure, but they have done nothing to build audiences and may have even acted as a deterrent.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.What does the general public want? It wants things that are familiar – like portraits or landscapes. It likes shows in which there is some guarantee of quality, whether it be a famous name such as Picasso or Monet, or a time-honoured topic, such as ancient Egypt. If an institution can tick these boxes, it buys itself considerable leeway for more marginal, experimental activities.

This is precisely what the NGV has done, in contrast to most of its rivals. A pay show such as Cats and Dogs helps subsidise a more challenging exhibition such as the Reko Rennie survey, its neighbour at Federation Square.

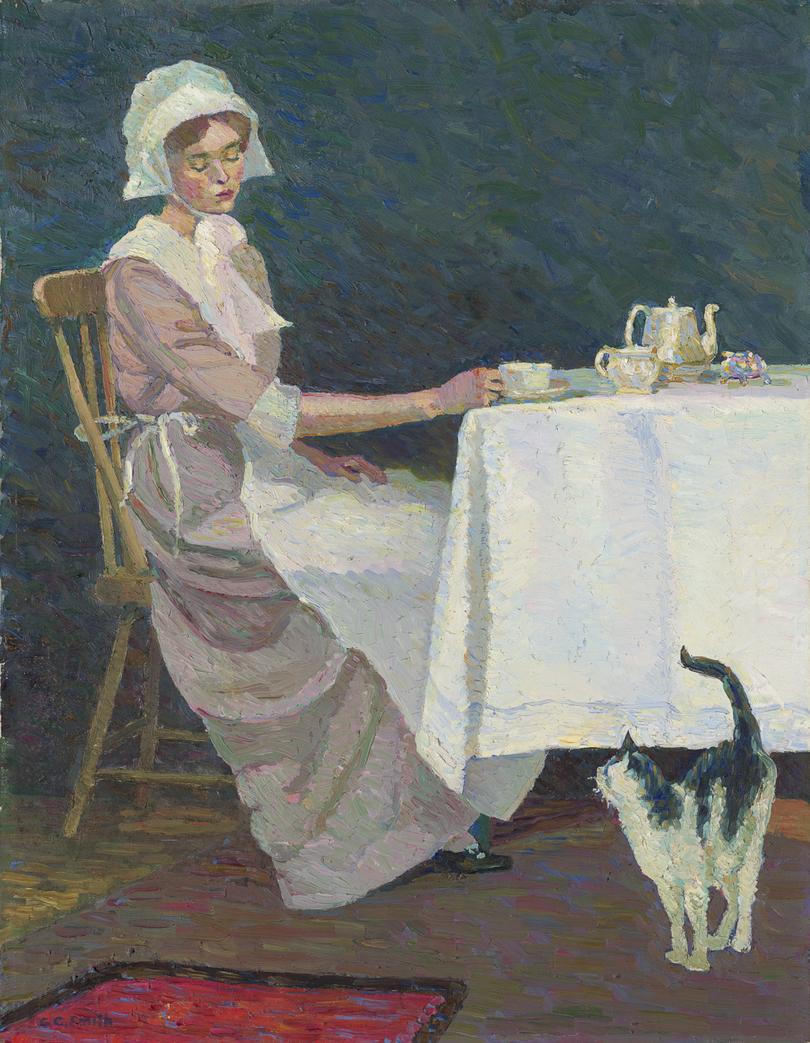

The first impression one take away from Cats and Dogs, is that it is a show virtually without boundaries. Along with dedicated images of these animals – in the form of paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, sculptures and items of applied art – there are numerous works in which a cat or dog appears in a supporting role. Balthus’s nude leans back in her chair to play with a cat; a dog sleeps by the bed on which a Bonnard nude lies stretched out in post-coital disarray. Balthus’s cat is as frisky as the model, Bonnard’s dog sleeps as soundly as its mistress.

On many occasions, animals in art are used to emphasise human characteristics, or comment on them. A dog acts as a classic symbol of faithfulness in Gainsborough’s portrait, Richard St George Mansergh-St George (c. 1776-80). The pooch looks longingly at his master who is dressed in the uniform of a redcoat, ready to sail for the rebellious American colonies.

Cats have a very different reputation, being known for their aloofness and independence. This is precisely what “dog people” dislike about cats, but for their owners, it’s a sign of distinction. Dogs are pack animals who need company, whereas cats seem happiest roaming by themselves. Louis Wain portrays a cat in the guise of a riotous Bohemian, complete with cane and monocle, in his cartoon, We won’t go home till morning (c. 1900-10)

I’ve always been a dog person, but with family and friends who are fiercely devoted to their cats. The arguments on behalf of one animal over the other are so well rehearsed it would be tedious to go over them, as neither side is willing to change its allegiance. In this show, even the curators seem eager to defend their respective corners.

“Cats are truly wonderful creatures,” gushes Laurie Benson, in an unscholarly moment, whereas Imogen Mallia-Valjan reminds us that “dogs aren’t just pets, but members of the family.”

As all shows seem to require an Indigenous component nowadays, it seems to have been relatively easy to find Aboriginal paintings and sculptures of dogs, but not so with cats. Some of these dog pieces are obvious inclusions, such as those painted wooden sculptures from Far North Queensland, which come uncomfortably close to tourist collectables. For a more inventive approach, one might look to Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri’s Dingo Dreaming at Marruwa (1988), in which the characteristic dots and circles of western desert painting are punctuated by paw prints. An anonymous bark painting from Groote Eylandt, called Dogs fighting (c. 1960) is a small masterpiece of frozen action.

Curator, Michael Gentle, tells us it is wrong to classify quolls as “native cats”, then follows with a series of quoll pictures. Despite a superficial resemblance, quolls are not related to cats at all.

The big problem may be that this exhibition seems broadly committed to a positive view of its subject, and in the outback, cats are a menace. A long-term association with the Australian Wildlife Conservancy has drilled into my mind the appalling fact that there are more than 5 million feral cats in Australia, and each of them kills 4-5 small creatures every night. It’s an ongoing holocaust that has driven many native species to extinction.

These ferals are not like your domestic toms and tabbies, or like any other predator, as they kill for pleasure – or by instinct – even when they’ve satisfied their hunger. The most appropriate image that springs to mind is Picasso’s Cat Catching a Bird (1939), from the Musée Picasso in Paris. There’s little in the NGV show that reveals the cat’s savage side, with the possible exception of a satirical etching of 1801, by Charles Williams, in which an elderly woman has her bottom lacerated by a group of brawling felines.

If cats get any bad press in this show, it’s purely in the role of witches’ familiars in etchings by Goya and other old masters. This is denounced as the product of ignorance and superstition, with the cat as the victim. In the prints of Japanese artist, Ishikawa Toraji, they become emblems of sensual abandon. Other works put the emphasis on their sheer elegance.

By contrast, there’s something lumpen, if lovable, in the way dogs have been portrayed. In clunking, academic paintings such as Septimus Power’s Staghunt, Exmoor (1911), or Briton Riviére’s Deer stealers pursued by stealth hounds (1875), we see hunting dogs in their most obedient guise, chasing deer or deer poachers. This show presents a rare opportunity to get these ponderous works back on the gallery walls.

In other images, such as a 1960s fashion photo by Athol Shmith, the dog becomes a kind of toy – no less of an accessory than a designer handbag. The poodle, with its artfully sculptured clip, is the antithesis of Power’s slavering beagles or the hard-working cattle dogs depicted by S.T. Gill and Will Dyson. As with the cats, there is very little interest in portraying dogs in a negative light. For all we know, the hounds that Rubens shows smooching up to Diana, goddess of the hunt, may have just torn Acteon limb from limb. Here, all they crave is a pat on the head.

In art, as in literature, we see ourselves in our pets, and sometimes better versions of ourselves. The poet, Christopher Smart, believed that his cat, Jeoffry, “a mixture of gravity and waggery,” knew that God was his saviour. Odysseus’s dog, Argos, waited 20 years for his master to return from the Trojan War.

The ideal piety and loyalty we ascribe to animals serves as a constant reminder of how far short of these goals we fall in our own lives. As human beings we may be the masters, but we can’t help but admire those cool, stylish cats, those trusting, humble dogs. These images of animals make us realise how out of step with nature we have become, and where we need to reconnect.

Cats and Dogs in Art and Design

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Until 20 July 2025