Ouroboros art review: At $14m is the most expensive purchase ever by the National Art Gallery worth it?

Australia’s leading art critic John McDonald runs his eye over the most expensive work ever purchased by the National Gallery and asks: ‘Is it worth it?’

“One of my great catchphrases,” says Lindy Lee, “is that cosmos is the length, breadth and depth of everything that has ever existed, exists right now, and will exist into the future and we can never fall outside that web of interconnection.”

As catchphrases go, it’s a bit longwinded, and very similar to what Aboriginal people call their Tjurkurrpa, but this is the subject of Ouroboros, Lee’s large, shiny new public sculpture now installed out front of the National Gallery of Australia.

There’s been a lot of fanfare associated with this commission, largely because of the price tag. The NGA admits to $14 million, although it’s rumoured to be even higher.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The gallery has staged a public relations blitz intended to make us feel relaxed about the staggering cost of the work, emphasising its “spiritual” aspects.

Judging by the insipid, feel-good coverage the work has received in the media so far, that campaign seems to be working.

But it’s not easy to overlook the price tag when it has been trumpeted from day one as a badge of the sculpture’s importance.

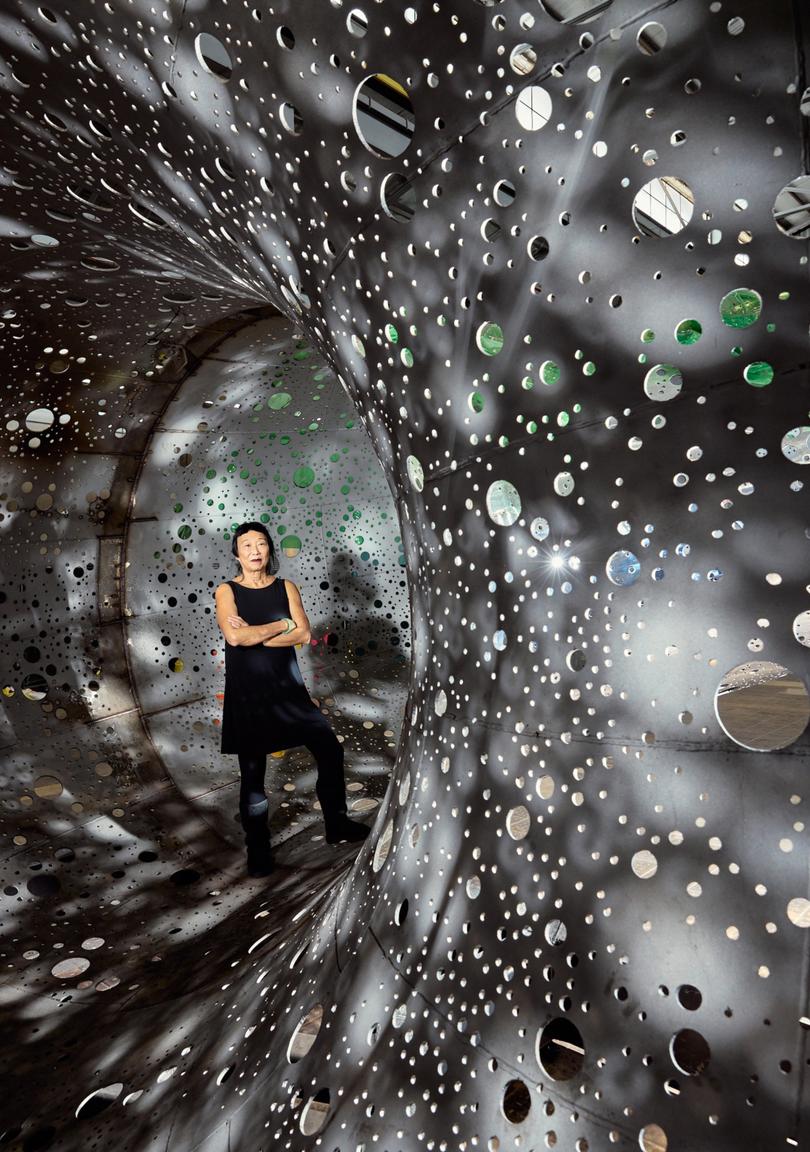

Lee’s Ouroboros, an abstract rendering of an ancient symbol of regeneration, featuring a snake swallowing its own tail, is the most expensive work ever purchased by the NGA.

To put matters into perspective, Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles set us back $1.3 million (US$2 million) in 1973, before the Aussie dollar was devalued.

Closer to the present day, a huge permanent installation by James Turrell, purchased under the NGA’s previous director, Ron Radford in 2010, cost $8.2 million.

One big difference is that Pollock and Turrell are both world-renowned artists who appear in all the histories of modern art.

Lee (b. Brisbane, 1954) is an Australian, without overseas representation, whose highest auction price at the time the work was commissioned was less than $10,000.

In 2018 Lee’s six-metre-high sculpture, The Life of Stars, was purchased for the Art Gallery of South Australia for $550,000.

It was touted as “a farewell present” for director, Nick Mitzevich, who was leaving Adelaide to take up the job at the helm of the NGA.

Within three years of arriving in Canberra, Mitzevich decided that Lee was the ideal artist to undertake a huge commission in celebration of the gallery’s 40th anniversary.

If 40 seems a rather arbitrary number alongside 50 or 100, it’s a reasonable excuse for a party.

Two melancholy observations: firstly, the tendency of museum directors to repeat their greatest hits from a previous job in their new posting; secondly, the desire of directors and curators to act as star-makers, keen to propel some favourite artist to the heights of their profession.

This is precisely what we’ve seen on this occasion, and the price tag has played a leading role.

The Life of Stars is roughly two metres taller than Ouroboros, but more than $13 million cheaper.

Both sculptures are made from perforated stainless steel and illuminated from within.

The chief difference is that Ouroboros is “immersive”, which means, in practice, one can walk a short way inside the metal shell on a catwalk. There’s also the cost of landscaping, as the work resides in a pool of water.

Talking with complete strangers during two visits to the sculpture last week, their big question was: “How do they account for all those millions?” One man’s answer was simple: OPM: Other People’s Money.

There seems to be no limit to what a gallery can spend if the money is coming from the taxpayer or from well-heeled private donors.

In the catalogue, Lindy Lee: The Making of Ouroboros, one reads much about the deeply spiritual nature of the work, including regular comments from Aunty Jude Barlow, “the National Gallery’s Elder in Residence” for the project.

There are four full pages of names, listing everyone who did anything at all in relation to the sculpture — including past and present Arts Ministers, members of the NGA Council, members of the NGA Foundation, NGA staff, everyone who works for the foundry, UAP, and on and on — like the credits at the end of a Hollywood movie.

There are also pages of technical drawings and statistics, to convince us of the “60,000 human hours” and more than “200 pairs of hands” involved in the fabrication.

The only thing missing is a breakdown of costs and a clear indication of who footed the bill.

Despite this Cecil B. DeMille cast, I remain deeply sceptical about the price, as do many sculptors with whom I’ve discussed this project.

No-one with any experience of large-scale sculpture can account for those extra millions, no matter how much the foundry doth protest.

One partial explanation may be found in this statement by Eve Willems from UAP: “The choice of cast recycled stainless steel meant the implementation of an induction furnace, so ensuring we could upgrade our workshop equipment and capacity was a crucial part of our project start-up.”

It sounds as if the NGA, in the search for “Australia’s first sustainable work of public art,” may have paid for an induction furnace and an extensive upgrade of the UAP workshop.

I have no idea what this might have cost, but it wouldn’t have been cheap.

A final irony is to find Nick Mitzevich on the ABC News website saying: “We’ve been very careful in the commissioning. We’ve ensured that we’ve strived for value for money.”

This is a piece of spin that would do Donald Trump proud: spend $14 million on one sculpture, then tell everyone this represents value for money.

Nobody at the ABC — in multiple reports on the work — seems to have bothered to query this claim.

To be fair, there has probably been only one dissenting voice so far in all the media — Christopher Allen in The Australian, who wrote it was: “an absurd sum to pay for a work of debatable value by an artist of Lee’s modest standing.”

This is the voice of common sense, only slightly tarnished by the fact that the writer has yet to see the work fully installed.

I’ve known Lindy Lee for decades and can vouch for her as a good person and an artist of integrity, but that’s a very long way from how she is being currently treated.

Until recently Lee was indeed an artist “of modest standing,” but in the NGA catalogue she has become a “revered Chinese-Australian artist.” Hail to thee, St. Lindy!

This statement is uncredited, but the catalogue is edited by Claire Summers, who works for Lee’s dealers, Sullivan + Strumpf.

I can’t think of another occasion when a public gallery has allowed a dealer to edit an exhibition catalogue, but Mitzevich is a specialist in blurring the line between public and private, having hosted a solo show by British artist, Sarah Lucas, in which all the work was supplied by her London dealer, Sadie Coles.

As usual, no journalist seemed to find this at all noteworthy.

A supplementary show of work by Lindy Lee, held within the gallery, could likewise be seen as a shop window for her dealers.

A smaller, golden version of Ouroboros, called Abundance, has been created by the precious metals conglomerate, Pallion, and is being exhibited in the gallery.

The baby sculpture is valued at $10 million and has already been through a special “blessing ceremony” with Indigenous elders at the Mt. Rawdon mine in Queensland.

In addition, there is the limited edition, gold and jade Xiaolong jewellery collection, designed by Lindy Lee, featuring a ring, earrings, pendant and cuff bangle.

This is available for purchase at the NGA, with proceeds going back to the gallery.

The jewellery, we read, “represents the deep connection she shares with jade and gold”.

If this plunge into high-end merch sounds a little tacky, it’s especially hard to square with all the lofty Zen and Dao references in the catalogue.

When I read about Lee’s “abiding exploration of materiality”, whatever that means, I wondered if they meant to say: “materialism”.

I also wondered if there could be anything less Zen than a 13-tonne metal sculpture, although here I must defer to the superior wisdom of the artist, a practising Buddhist.

Nevertheless, when Lee talks about the sculpture being “silent and still”, this may be a function of its sheer bulk rather than its mystical aura.

After all this, when I finally took a close look at Ouroboros, it was astonishing to see how crudely it had been finished.

From inside, those thousands of perforations became very wonky circles with rough edges.

Plates had been welded together leaving prominent ridges that tended to detract from the work’s cosmic pretentions.

Looking down, where the internal surface touched the water of the pond, there were already traces of rust.

It appears that $14 million doesn’t buy perfection.

The sculpture works better at night when the light seeping through the perforations makes for an arresting spectacle.

It’s a thrill for the eyes, but as a vision of “the cosmos” the concept is too vague and all-encompassing to be taken seriously.

It would be better to say it’s a vision of the cosmos for those already predisposed to see it that way.

By way of comparison, think of another public sculpture by a Chinese-Australian artist: Tianli Zu’s Triumph (2018), which commemorates a strike by maritime workers who refused to load a shipment of iron bound for Japan in 1938, following the Nanjing massacre.

Four metres high by four metres wide, made from rusty cor-ten steel, it’s a bomb split in two, symbolising the workers’ efforts to stop feeding the Japanese war machine.

Situated on the coast at Port Kembla, this sculpture refers to a specific event that suggests a solidarity between the Australians and the Chinese.

Zu’s sculpture is the obscure, working-class cousin of Lee’s gleaming abstraction.

At a time when most art galleries were starved for resources, coming out of the COVID-19 lockdowns, it was a strange, insensitive decision by Mitzevich to announce the NGA would invest a huge amount of money in a single work by an artist whom no-one would describe as a genius for the ages.

Another dealer suggested to me that if Mitzevich had wanted to make an impact and spread good will, he could have given 14 artists a million dollars each and said: “Make me the work of your life.”

Lee could have been one of that group rather than being placed on a lonely, unrealistic pedestal.

If she clears only 10 per cent from the price, at $1.4 million it will be by far the largest ever payday for a living Australian artist.

One gets the impression Mitzevich thought he would be congratulated for investing so heavily in a work by a female, Chinese-Australian artist, as if our contemporary obsession with gender and ethnicity were sufficient to get everyone on-side — or at least forestall criticism.

Factor in numerous Indigenous references as further insurance and what could go wrong?

The reality is that our marshmallow media may have taken the bait and written endless gooey reports about Lee and the sculpture, but the project has made a very bad impression with artists and dealers who see this as an act of outrageous favouritism.

Many sculptors think of Lee as a designer who gets her works made by assistants and factories, with relatively little personal involvement aside from the working drawings.

She cheerfully admits that the difficult engineering specs were left to the foundry.

“It’s simpler than you might expect,” she says in the catalogue.

“I come up with the drawing or the idea, and I simply hand it over to Dan and say, ‘Work it out’.”

Four years ago, when I saw the working design for this sculpture, I thought it looked less like a snake than a very large, shiny bagel.

Having seen the finished product, the idea of The Big Bagel seems more apt than ever.

The NGA may have thought they were investing in a vision of the cosmos, but instead they’ve bought a roadside attraction.

Lindy Lee: Ouroboros

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.