The Economist: Can Lego remain the world’s coolest toymaker?

The world’s biggest toymaker relies on keeping its customers — young and old—enchanted

The Venus de Milo; “Mona Lisa”; 250 skulls on a mirrored wall; a 6m Tyrannosaurus rex. You can see all this and more at The Art of the Brick, a touring exhibition currently in Berlin. It is the work of Nathan Sawaya, a former lawyer.

His chosen medium? Lego bricks.

Lego guards its bricks jealously. Early in Mr Sawaya’s artistic career, the Danish toymaker sent him a cease-and-desist order. Now a “Lego certified professional”, he builds with the firm’s blessing.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.At Lego’s headquarters in Billund, in Denmark, “master builders” work behind tinted windows, hidden from prying eyes. This year the EU’s General Court ruled in Lego’s favour in a trademark dispute with a German company.

“We are the most reputable brand in the world, so we want to be super-careful with our reputation,” says Niels Christiansen, Lego’s chief executive.

When you are the world’s biggest toymaker, that reputation relies on keeping your customers — young and old—enchanted. Mr Christiansen also believes it will depend on making Lego’s billions of plastic bricks in a way that is friendlier to the planet.

Lego did not begin with plastic.

Its founder, Ole Kirk Kristiansen, started the firm in 1932 as a maker of wooden toys, truncating leg godt, Danish for “play well”, to form its name. He patented his plastic bricks in 1958 (and died later that year). Two years on, after a fire destroyed its wooden-toy warehouse, Lego chose to stick with only plastic bricks.

Lego nearly went under in 2003-04 after branching into too many areas, such as children’s clothes and dolls. Jorgen Vig Knudstorp, who became chief executive in 2004, sold its theme parks and refocused the firm on bricks and articulated “minifigures”. Under Mr Christiansen, who took over in 2017, Lego has continued to thrive, while most rivals have struggled with the toy business’s ever-shifting fads.

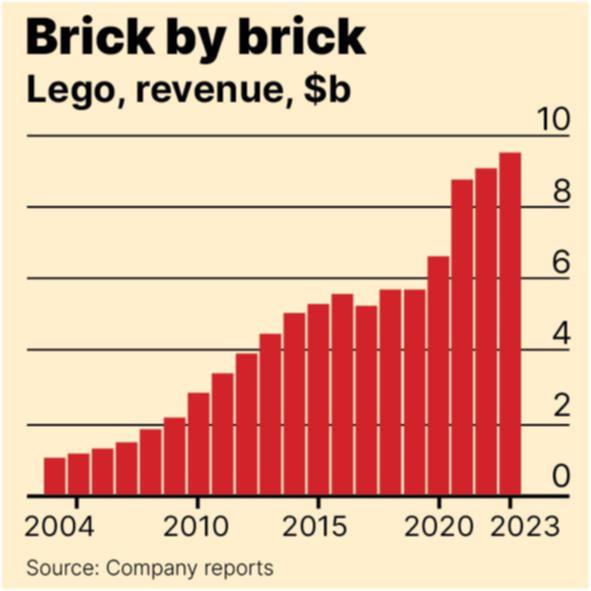

Over the past 20 years the company’s revenue has grown ten-fold, reaching $US9.7b in 2023. A decade ago it became the world’s largest toymaker by revenue.

Today its sales are greater than those of its two biggest rivals — Mattel, creator of Barbie, and Hasbro, maker of Nerf guns— combined. In 2023 it opened 147 shops around the world, taking its total to ,031, and built factories in America and Vietnam. Sales in the first half of 2024 were up by 13 per cent, year on year, even as the global toy market shrank. In 2004 the company was loss-making; in 2023 its net profit was $US1.82b implying an enviable margin of nearly 20 per cent.

Can the toymaker maintain its success? “We need to stay relevant for kids and adults,” says Mr Christiansen. New sets keep coming; nearly half the products in its range in 2023 were released that year. The firm also makes more than 140 elaborate sets, some with thousands of pieces, for adult fans of Lego (AFOLs), who now account for one-fifth of sales.

But competing with the online world for time is hard. On average, American children aged 8-12 spend 4-6 hours a day watching screens of various types, from smartphones to televisions, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

That is why in 2022 Lego invested in a partnership with Epic Games, maker of Fortnite, a popular video game, to build “engaging digital experiences for kids of all ages”. Their arrangement has proved lucrative.

So far Lego’s attempts to find a green alternative to plastic, the company’s other big challenge, have been less successful. Still, Mr Christiansen plans to make bricks entirely from sustainable material by 2032.

Lego has started manufacturing some pieces with a new plastic made using renewable energy and recycled material. Renewable resin is up to 60 per cent dearer than plastic made of fossil fuel, but Mr Christiansen says he is prepared to absorb the cost. By buying lots of it, he hopes to create a market for the material and push its cost down. He intends to reduce Lego’s carbon footprint by 37 per cent by 2032 (compared with 2019) and be carbon neutral by 2050.

Family ownership allows Lego to take the long view, Mr Christiansen says. (A foundation owns a quarter of the firm; the Kristiansen family owns the rest.)

After 2032 the path to carbon neutrality will be steeper, he admits, but “we serve kids”— the inheritors of the planet. And, he surely hopes, tomorrow’s AFOLs.