The Economist: Five months out, Donald Trump has a clear lead over Joe Biden

America’s presidential race is no coin flip, says The Economist’s forecast, which has Donald Trump as the favourite.

Joe Biden’s job-approval rating stands at 39 per cent, putting him roughly in a tie for lowest of any president at this point in his term in the history of American polling. In all six states that could prove decisive he trails by between one and six percentage points. In the two where he is closest, Wisconsin and Michigan, Democratic candidates’ margins have under-performed the final polls by an average of six points in the past two elections. Even if he wins both, Mr Biden would still need one more swing state to secure the 270 electoral votes necessary for re-election.

These numbers suggest that the race is hardly a “toss-up”. True, the five months remaining before the vote give Mr Biden time to make up ground, and the polls may underestimate his true support. But it is also possible that his deficit could widen, and that the candidate to benefit from any polling error could be Donald Trump.

In 2016 most pundits and forecasters found it unfathomable that a manifestly unqualified candidate like Mr Trump could win the presidency. This bias was reinforced by polls that consistently put Hillary Clinton in the lead. Now, after a tumultuous presidency that yielded two impeachments and a riot at the Capitol, the prospect that voters might willingly return to office a man recently convicted of 34 felonies seems nearly as outlandish.

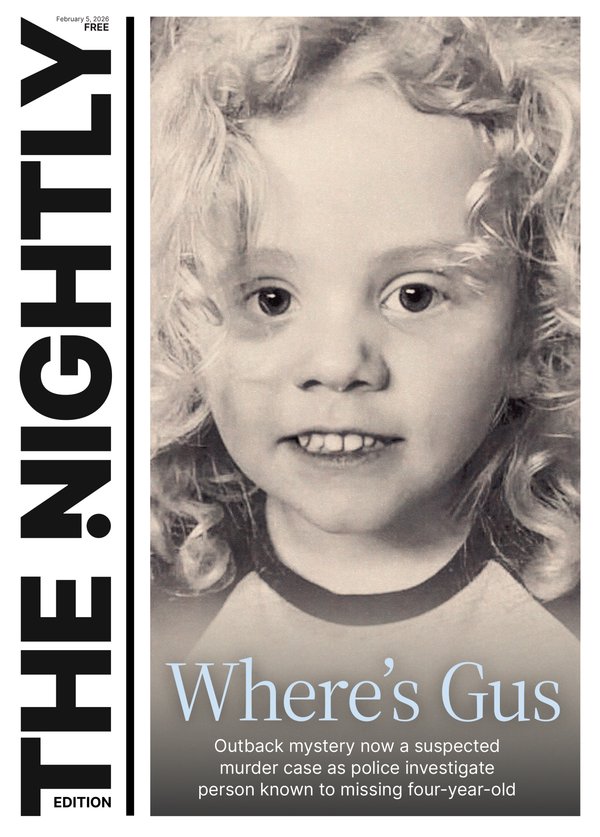

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Yet surveys suggest it is more likely than not. The Economist’s statistical model of the election—which relies solely on polls, past results and economic data, and knows nothing of Mr Trump’s statements or record in office or in the courts—gives Mr Biden a 34 per cent chance of staving off a second Trump term. That means a victory for Mr Biden would count as only a mild surprise, somewhat more likely than the 30 per cent share of days on which it rains in London. Four years ago this week this model gave Mr Biden an 83 per cent chance.

Our model combines two types of data: horse-race polls and “fundamentals”, or expectations based on historical precedents. Its starting-point, drawing on work by Alan Abramowitz of Emory University, is a national “fundamentals forecast” that seeks to predict the incumbent party’s share of the vote (excluding third-party candidates) based on three factors: the president’s approval rating, incumbency and the economy. We have reinterpreted Mr Abramowitz’s incumbency advantage as the absence of a “term penalty” suffered by parties seeking to hold the White House for more than eight years, a feat accomplished only once since 1950. We also account for the weakening of the link between economic performance and the vote shares of incumbents seeking re-election, due to growing polarisation of the electorate into camps of committed partisans.

As anyone who followed American politics in 2000 or 2016 knows, winning the popular vote is no guarantee of prevailing in the state-by-state electoral college. Our model also includes a fundamentals forecast for each state, based largely on how much more Democratic or Republican its past results have been than America as a whole. For example, in 2020 Mr Trump won Florida by 3.3 percentage points while losing nationwide by 4.5, putting Florida 7.8 points to the right of the country.

Our model then hunts for the true voting intentions in each state, on each day, taking into account opinion polls published so far. It adjusts for the impact on survey results of methods, sample sizes, pollster biases and the use of likely-voter screens. Every day, the model generates 10,001 different possible scenarios for the election. The most common ones land close to poll results and its fundamentals forecasts. But it also includes a healthy number of big surprises, to allow for the risk of significant polling errors.

In 2012 the overall picture painted by state-level surveys turned out to be more accurate than nationwide polls; four years later, the reverse was true. To avoid over-weighting either type of survey, the model treats the election as a giant jigsaw puzzle, in which vote shares in each state have to add up to the national total. An unusually strong national poll for a candidate will yield higher expected vote shares in every state. Conversely, a surprisingly poor state-level poll for a candidate will lower the model’s expectations not just in that state but nationwide, especially in places that are nearby and demographically similar.

Why it’s looking bad for Biden

Starting with the national fundamentals, our model’s expectation for Mr Biden (before seeing a single horse-race poll) is that he should win 50.5 per cent of the two-party vote—a bit above his current 49.4 per cent share in national polls, though below the 52.3 per cent he won in 2020. The model thinks he is slightly more likely to gain ground on Mr Trump during the next five months than to lose it: on average, it expects Mr Biden to pick up half a percentage point, yielding a tie in the national popular vote.

Unfortunately for the president, state-level polls do not suggest that the electoral-college advantage Mr Trump enjoyed in 2016 and 2020 has eroded materially. Mr Biden trails by around five points in the Sun Belt battlegrounds of Arizona, Georgia and Nevada, all of which voted for him four years ago. Our model gives him just a 24 per cent chance of holding on to Georgia, where his lost popularity with black voters is most damaging, and 31 per cent and 36 per cent shots in Arizona and Nevada, where his losses among Latinos hurt him.

Mr Biden’s polling has held up far better in the relatively white Rust Belt swing states of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which is consistent with nationwide surveys showing that his standing among white voters has barely changed since 2020. Mr Trump leads narrowly in all three states. Our model considers all three close to coin flips (see chart). State-level vote shares in the Great Lakes region have tended to fluctuate in tandem from one election to another. It would take only a tiny improvement in Mr Biden’s numbers or polling error in his favour to hand him the trio, and a second term.

However, there are two reasons why Mr Biden’s true chance of winning the electoral college is lower than the average chance of victory that the model gives him in these three states. First, his slide in other regions makes it less likely that he can make up for a loss in the Midwest with wins in the South or West. If he loses Arizona, Georgia and Nevada, he then needs all three Rust Belt battlegrounds (plus one electoral-college vote from Omaha, Nebraska) to muster exactly the magic 270. Our model gives Mr Trump a 43 per cent chance of winning them all and Mr Biden 31 per cent, leaving 27 per cent for a split decision that would probably also return Mr Trump to the White House.

Second, in both 2016 and 2020 Mr Trump did far better in the Midwest than surveys implied. Our model assumes that both candidates are equally likely to benefit from polling errors. But if you compare current surveys with state-level polling averages from late 2020, rather than with the actual election results, the Rust Belt no longer looks like a Biden-friendly outlier. Instead, it is consistent with a national trend, in which Mr Trump appears to have gained three to five points of vote share. If that were the case, the former president could be on track for a decisive victory, flipping light-blue states like Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire or Virginia. Recent polls showing a tied vote in Virginia, or Mr Biden’s lead in the Democratic bastion of New York dwindling to a modest nine-to-ten points, bolster that possibility.

Mr Biden’s situation is far from desperate. Good news for him or bad news for Mr Trump—such as the former president’s recent conviction in New York, which has been reflected in only a handful of state-level surveys so far—could shift their chances. So could the presidential debates. Moreover, the Democratic Party’s new base of white voters with college degrees is far more likely to turn out than Mr Trump’s less-educated coalition is, a disparity that pollsters’ likely-voter screens may not fully reflect.

Our model gives Mr Trump better chances of victory than do other public quantitative forecasts. A model by Decision Desk HQ and The Hill puts him on 56 per cent. The forecast released on June 11th by ABC News’s FiveThirtyEight expects Mr Biden’s position in swing states to improve enough between now and November to give him an edge, with a 53 per cent win probability. All three forecasts agree that the contest is close, and that a victory for either major candidate is easily plausible. But by our reckoning, Mr Trump is the favourite.