Australia’s Roo-ver lunar rover set for historic Moon’s South Pole mission on NASA Artemis III launch in 2027

Australia’s pioneering lunar rover, ‘Roo-ver’, will join NASA’s Artemis III mission as the first manned exploration of the Moon’s South Pole in over 50 years.

Roughly two years from now, if all goes to plan, a lunar rover will roll down the ramp of NASA’s Artemis III lander on to the Moon’s South Pole.

It will be a crucial moment in one of the most complex feats of engineering and human endeavour in the history of deep space exploration, and emblazoned on the side of the rover will be the Australian flag.

When this moment is beamed to billions of people watching around the world, it’ll be the most conspicuous display of Australian innovation since the 1983 America’s Cup.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Back then, it was the radical winged keel on Australia II, designed by Ben Lexcen, which broke the New York Yacht Club’s 132-year stranglehold on the world’s most prestigious sailing race.

The Aussie lunar rover, officially dubbed “Roo-ver” after a public naming competition, is part of something even more historic, joining the first manned mission to the Moon’s surface in more than 50 years and the first to its southern pole.

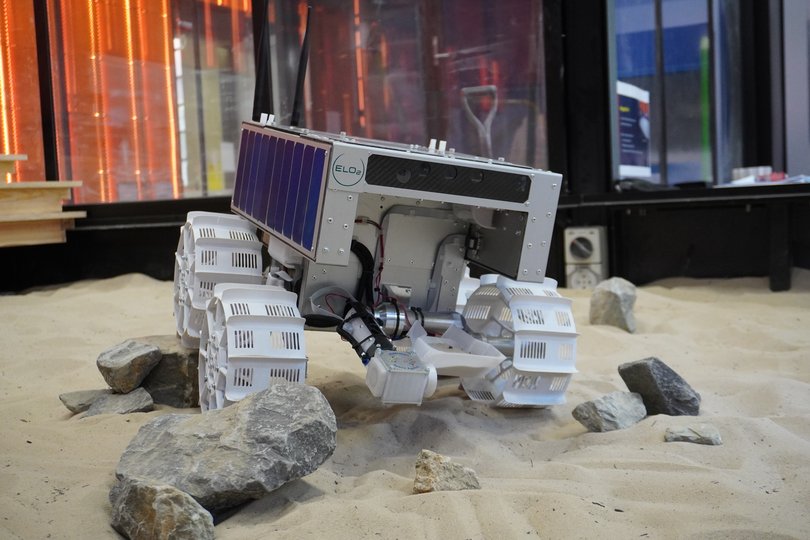

After the Australian Space Agency reached an agreement with NASA in 2021 to supply an Australian-made, semi-autonomous rover to the mission, two local consortiums, ELO2 and AROSE, each received $4 million to develop prototypes.

The overarching goal was to leverage this task to foster innovation, both in Australia’s nascent space industry and across other sectors.

So, each consortium combined space startups, major resources companies, universities and other research partners.

ELO2 won the ensuing design competition, and mission director Ben Sorensen says the America’s Cup victory is a source of inspiration for the considerable work that lies ahead.

“That real national pride of being an underdog and really achieving more than what people realise Australians can achieve, that’s a big part of the job,” Mr Sorensen tells The Nightly.

Now armed with a $42 million grant from ASA, the consortium is comprised of 10 Australian universities, including Australian National University, RMIT and Edith Cowan University, mining giant BHP and defence tech company EPE.

Mr Sorensen talks about lines of effort when considering how the project will come together, starting with the effort required to overcome the significant technical challenges involved.

Less obvious is the effort that will be invested in communication and outreach, aimed at inspiring the next generation of Australian space industry workers to pursue STEM pathways in school.

Arguably the most important line of effort to Australia’s future will be directed towards growing capacity and capability in the nation’s space industry.

“It’s the technologies that we’re creating and developing with our partners from Australia’s great research universities and our industry partners, who are great at building things that work really well,” Mr Sorensen says.

“Take things that Australia is already really strong at, and how do we help grow productivity in those areas, and how do we improve and provide competitive advantage for those companies and industries when we go to compete overseas.”

ASA head Enrico Palermo says Roo-ver will demonstrate the cutting-edge capability Australia can offer to major global space missions like Artemis.

“The Roo-ver Mission is as much about the journey as the destination,” Palermo says.

“Roo-ver is one of the most advanced robotics and manufacturing projects in Australia right now.

“It is a prime example of how space can drive the Australian Government’s Future Made in Australia agenda to grow our nation’s industrial capability, boost productivity, and build economic resilience.”

Roo-ver is expected to weigh about 20kg and will be about the size of a suitcase.

It will take commands from a mission control centre in Australia, 384,000km away, which will be integrated with communications infrastructure in the US and other locations across the world.

Across eight days, operating only when the sun is hitting its solar panels, Roo-ver will collect samples of regolith and return them to the lander for testing by the astronauts.

NASA believes lunar regolith can potentially hold oxygen, which would be pivotal to setting up a sustainable human presence on the moon.

More than that, oxygen is a key element in rocket fuel and the ability to produce it at a future Moon base would support humanity’s grander ambitions that stretch much further into the Solar System.

“Establishing a sustainable human presence on the Moon and Mars is a key focus of the international space community over the coming decades, and the Roo-ver Mission centres Australia in that foundational work,” Palermo believes.

In August, NASA announced the Artemis III launch vehicle had moved from the Space Systems Processing Facility at NASA Kennedy to the mammoth Vehicle Assembly Building.

It’s there the rocket’s components will continue to be vertically stacked into early next year, when it will begin to undergo check-out testing once stage integration is complete.

Despite the immense scale — the Artemis III launch vehicle contains nearly 30km of cabling alone — the perilous nature of space travel requires every millimetre of the rocket to be meticulously tested to prevent catastrophic failure.

Paradoxically, failing is an integral part of what ELO2 is trying to do.

“There’s a great acronym, FAIL, that means First Attempt In Learning, and I think we should fail more often,” Mr Sorensen explains.

“You prototype, you test, you iterate, and at the core of all that is humility in that no one person has all the answers, and no one can tell the future.

“We work really hard to remind ourselves of one really simple thing — you get outside the atmosphere, you’re dead.

“So, you start there. Can we now make that less likely for every kilometre we go towards the Moon, and every minute that we spend on the Moon.”

Every minute Roo-ver spends on the Moon brings other challenges the team must overcome, succinctly described in that old adage of the industry, “space is hard”.

“Our job is to build something that can operate in a vacuum environment, in an environment which also is very dusty,” Mr Sorensen says.

“And that dust … is highly abrasive, it’s sharp, it gets into places and it’s also got electrostatic properties, which can affect the operation of Roo-ver on the Moon.

“The environment is 160C in the sun, and then on the other side of the rover (in the shade), it’s -120C.

“The South Pole is over three and a half billion years old, it’s one of the oldest parts of the Solar System, so it’s novel for humans to be there and to work in that environment.”

When pressed on the main challenges the project faces, Sorensen pivots instead to a discussion about opportunities, and high on his list is pushing closer collaboration between research institutes and industry.

It’s an area in which Australia has historically been a laggard among OECD nations.

“You can’t force marriages in these things,” Mr Sorensen admits. “The incentives have got to be right for different groups to come together, and that’s about having a shared vision.

“But implicit in that is a shared understanding of either one of two things — the threat or the danger if you don’t do something, or, on the other side, the magnitude of the opportunity for doing it.”

The threat, in this instance, is Australia will finish at the back of the pack in the space race, which has serious economic ramifications.

Estimates put the cost of the Artemis program at upwards of $150 billion to date, which seems like an eyewatering sum until you hear the value of the space industry last year was more than $938 billion.

Even a sliver of that pie would be a massive fillip for the Australian economy, as Sorensen, Palermo and Anthony Albanese are well aware.

Not that Sorensen will be thinking of economic development when Roo-ver rolls on to the surface of the Moon in mid-2027.

He’ll see the Aussie flag on the side and be reminded of that America’s Cup victory.

A reason for the nation to celebrate, and, who knows, maybe the PM will channel Bob Hawke by proclaiming any boss who sacks a worker for not turning up is a bum.

“That’s it,” Sorensen laughs.

“A wonderful group of talented Australians have come together to do this important mission, and it’s a wonderful privilege and I’m thankful to have the opportunity to do it for Australia.”