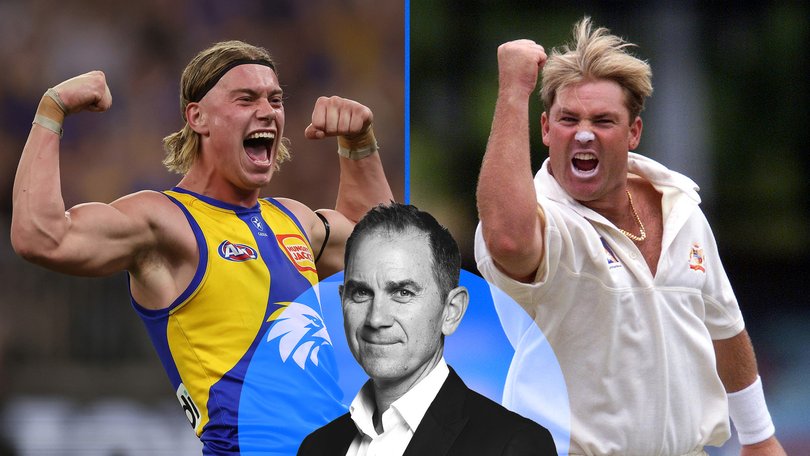

JUSTIN LANGER: Harley Reid like Shane Warne’s path to success will be a long and tough one

JUSTIN LANGER: Shane Warne’s rise to stardom was no easy road, as many of the latest stars in the making - like Harley Reid - are finding out the hard way.

Adam Gilchrist once said to me: “The best players believe in themselves. Average players want others to believe in them.”

At the time Gilly was giving me advice to be bold and brave and back myself in.

Life has shown me that backing yourself in and believing in yourself can be easier said than done and that confidence is earned; it must be earned, and it must be real, not fake. Life has also taught me that while you do have to believe in yourself, it doesn’t hurt having a few people in your corner.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Picture this.

Allan Border throws Shane Warne the cricket ball. The humidity is high, the heat higher. Australia is in trouble. Sri Lanka are cruising, to a first Test victory in Colombo.

In AB’s mind, throwing the ball to Warnie might have been a last throw of the dice. Those watching, probably called it madness.

Backing a bleach-blond kid whose bowling average had touched 346 in his first three innings as a Test cricketer, would have buried lesser mortals.

But captain Border saw something others couldn’t: the raw, untamed magic lurking beneath the heavy-looking surfer boy who had hardly made an initial impression on the game.

Going one step further, the start of Warnie’s Test career could be classified as an early disaster.

In his first Test, the 22-year-old Victorian leg-spinner trudged off the SCG after conceding 150 runs for just one wicket against India.

The critics sharpened their knives. Here was Australian cricket’s latest false dawn. “The kid, with a smart-arse attitude, who couldn’t turn the ball on a spinning top, let alone a cricket pitch”, they whispered.

Border, however, possessed the wisdom of a seasoned warrior who’d dragged Australian cricket up off its knees.

He’d seen enough raw talent to recognise the difference between terminal mediocrity and dormant greatness. When others saw failure, Border saw potential wrapped in nervous energy and misplaced confidence.

Following his poor first Test in Sydney, Warnie’s first innings in Colombo was another horror show — 0 for 107. Lesser captains might have hidden him away. Instead, Border threw him the ball when Australia needed three wickets to snatch victory from certain defeat.

What followed defied logic. Warnie took the final three wickets without conceding a run, a match-winning spell that left Sri Lankan captain Arjuna Ranatunga bewildered.

He said after the game: “A bowler with a Test average of more than 300 has just snatched victory from our hands.”

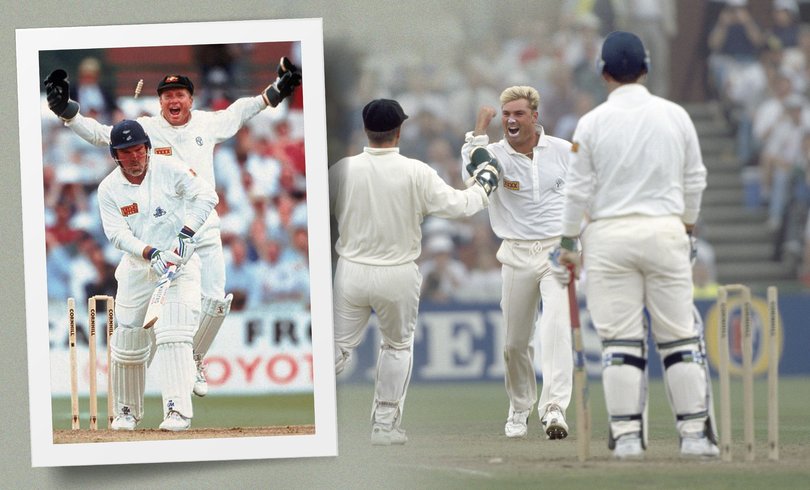

Eleven months later, that same kid bowled what is now known as the Ball of The Century.

At Old Trafford in England, the cricket world witnessed cricket’s most famous single delivery. A leg-break that ripped from well outside leg stump to canon into Mike Gatting’s off bail, pictured above.

In that single moment, a phenomenon, a rock star, a superstar was announced far more publicly than he was in Sri Lanka 11 months earlier.

By the end of his career, Warnie had played 145 Test matches, took 708 wickets, and set the record for the most wickets taken by any bowler in Test cricket — a record he held until 2007.

It was no wonder that when he died so sadly and suddenly, AB said at his testimonial: “Thank you for revitalising my captaincy towards the end of my time. I was lucky to have spent two years with Shane, and I just want to thank him for that, just quietly on my own.”

AB, and then Mark Taylor, had done more than back a young bowler; they’d nurtured cricket’s greatest magician through his darkest apprenticeship, proving that true leadership sometimes means believing in what others can’t yet see. They showed the foresight required to recognise the characteristics that might serve them in the long-term, not just the short-term of now.

In cricket alone, there are many examples. Steve Waugh took 27 Test matches to score his first Test century. Someone, or some people obviously saw something in him to ride out the wave of perceived failures. His captain was also Border, and the coach Bobby Simpson.

When Waugh became captain, he believed in players like Matty Hayden, the discarded Damien Martyn, Ricky Ponting, Glenn McGrath, Jason Gillespie, Adam Gilchrist and many others. It is no wonder they would all run through brick walls for him today.

When Ponting took over the reins, he again followed the proved strategy of identifying the best talent and then backing them in; even before they were able to back in themselves. Andrew Symonds, Brett Lee, Michael Clarke, Phil Hughes, Shane Watson are all examples of these players.

They all had their ups and downs, but they always knew their leader had their back.

This week in the West Indies, I watched with admiration as Mitch Marsh, Josh Inglis and Cameron Green led Australia to another T20 series win.

Mitch has the title of captain, while the other two dominated with the bat. I remember the journeys all three on them have been on.

None of them have been overnight success stories, having to fight for the opportunity to enjoy moments like they did in Jamaica on Tuesday.

When I am regularly asked who the Australian top three will be for the Ashes, I say without hesitation, that Green must bat at three this summer.

Most players have a breakthrough series before they come of age and step up from apprentice to a qualified Test player. At 26 years of age, and with 32 Test matches and two Test centuries under his belt, Green has proved he is ready to go.

In the last series in the West Indies, Pat Cummins gave him the opportunity to step into the coveted number three spot, and in the toughest of conditions he demonstrated he has what it takes to make that role his own.

I hope the captain and selectors hold their nerve and back Green in, because I sense his time has come to show the cricket world just how good he could be.

Having watched him since we contracted him in WA cricket as a 16-year-old school kid, I believe he is ready to shine in what should be an epic Ashes series here at home.

Few successes in sport or business will deny they had mentors who didn’t play a pivotal role in seeing them through the tough times of their apprenticeship years.

Last weekend I watched Caleb Serong, Andy Brayshaw, Luke Jackson, Hayden Young and co step up when their team needed it the most.

Against the league leaders Collingwood, they put on a performance that will have them and their supporters fully believing. Such performances aren’t fake, they are real. Such authentic, gut-grinding performances add layers to their confidence. With confidence anything is possible.

I am certain coach Justin Longmuir, and senior players like Nat Fyfe, Alex Pearce and Sonny Walters, were sitting in the stands proud and full of admiration for their young guns who are starting to spread their collective wings as they fly towards premiership contention.

They will also acknowledge that times like these have taken time in the making. Time well worth the nurturing.

In the same game, the Daicos brothers ran amok with their band of merry men, and although they fell short, I can only imagine they would attribute much of their success and development to their senior teammates such as Scott Pendlebury, Darcy Moore and Steele Sidebottom who have seen it all in the AFL.

At the other end of the spectrum, Harley Reid played his best game for West Coast despite his young team copping a third-quarter hiding by 17th placed Richmond.

Players and teams — just like Freo — take time to develop, grow and blossom. In the case of teams like the Eagles and Richmond, the leaders of their clubs must have hawk-eye vision for people and talent, just like Border had for Australian cricket.

In business, developing managers into CEO’s takes time and vision, just as journalists or lawyers need time, experience and guidance to step up to become editors, partners or judges.

Teachers don’t become the heads of their schools until they have stepped up the ladder and through the potholes of daily teaching challenges.

A politician can’t become a minister or the Prime Minister without earning the right.

Some will say their journeys are the result of all their own work, and while this may be the case, most journeys require others to hold the light up as a guide, at one point or another, especially when the cave is at its darkest.

Others may never be bold enough to take their first step into that cave without the encouragement and vision of those who believe in them.

Just ask the Shane Warnes of the world.