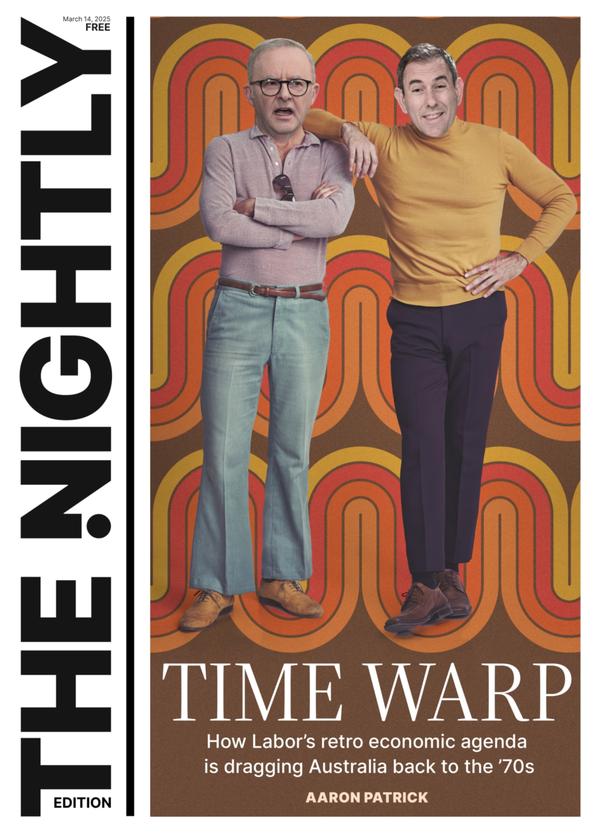

Albanese’s Legacy Part 1: How the Prime Minister’s economic policies are taking Australia back to the 1970s

On Thursday afternoon, a few cottage farmers gathered at a flower farm in a picturesque valley about an hour inland from Brisbane’s Moreton Bay. The 30 guests were offered a glass of locally made gin and appetizers from a nearby restaurant.

The free event, held to encourage “connection, conversation and community,” was run by the Food & Agribusiness Network, an agricultural-promotion organisation which last year received $2 million from the Albanese government.

The cocktail party was an example, in microcosm, of the government’s economic approach over the past three years: while claiming inspiration from the free-market philosophies of Labor governments in the 1980s and 1990s, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers have acted more like big-spending interventionist Labor politicians from the 1970s.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Their strategy can be summed up as: use a surge in taxation to fund expensive promises, including questionable business subsidies, and tax cuts that were quickly eaten away by inflation.

The looming March 25 budget will confirm the big-taxing approach. The document will show tax revenue hitting about $660 billion next financial year, $126 billion higher than when Labor came to power in 2022, economists believe. Not in almost two decades will a government have taxed Australians more as a proportion of the whole economy.

Big promises

Launching Labor’s election campaign three years ago, Mr Albanese promised “to embark on a new era of economic reform with productivity growth at the centre”.

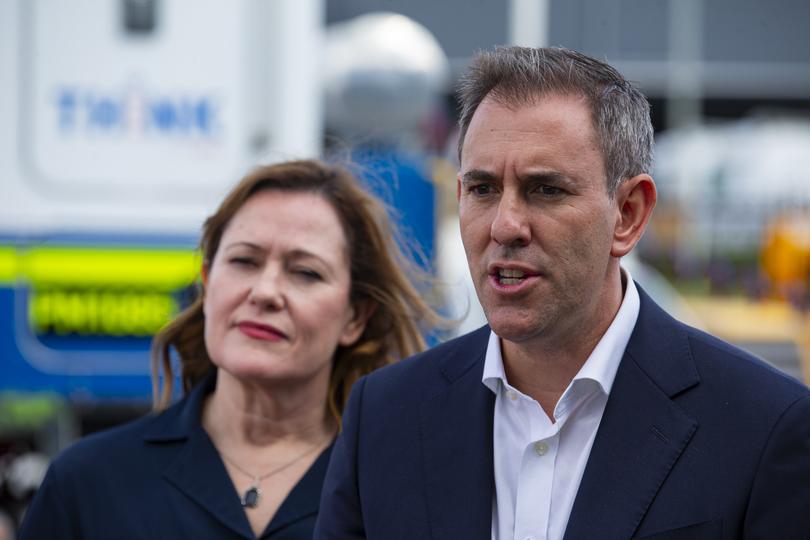

Many observers hoped it was true. Mr Chalmers’ adulation of former treasurer and prime minister Paul Keating raised expectations he would copy the older politician’s preference for private enterprise. But Dr Chalmers was too young to have worked in the Keating government, and his job before being elected was chief of staff to treasurer Wayne Swan, an advocate of government intervention.

“I think a lot of us wondered whether Jim Chalmers would follow in the footsteps of his hero Paul Keating or mentor Wayne Swan,” says economist Richard Holden, a professor at the University of NSW who studies economic policy closely. “I hoped it would be the former and it’s turned out to be the latter.”

The first challenge came quickly. As the economy emerged from the pandemic, a burst of inflation hit the world. In Labor’s first year in power, prices rose 7.8 per cent.

It was the most serious spike since 1990. Concerned the economy was overheating, the Reserve Bank of Australia jacked up interest rates. Although the central bank did not explicitly acknowledge it, one of its objectives was to increase unemployment, a political threat to the Labor government.

Mr Albanese and Dr Chalmers could have helped the inflation fight by cutting spending. Instead, they introduced new, expensive policies designed to stimulate an economy being knocked down by the central bank.

Some had a temporary effect on inflation, such as a $300 electricity rebate for every home. Others simply injected more cash into the economy, generating positive coverage but prolonging higher interest rates.

Central bank concerns

Even the apolitical Reserve Bank acknowledged government spending was hurting the inflation fight. As the central bank struggled to bring inflation under control through 2023 and 2024, it dropped increasingly blunt hints government spending wasn’t helping.

Last November, Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock discussed the problem with Mr Chalmers.

“My reading — when I speak privately to the Treasurer and when I hear him speak on television and radio — is that he’s fully aware of the inflationary implications of his own policies,” she said afterwards.

“He needs to be thinking about that.

“Because he — like me — understands that inflation is really what’s hurting people at the moment.”

The government didn’t change strategies even though inflation stayed higher for longer than in similar countries.

By November 2023, Australia’s inflation was higher than 15 similar economies, including the UK, France and Germany. Last year the International Monetary Fund predicted higher inflation would persist in Australia than in the US or Europe for the next five years.

Economists consider inflation the greatest economic threat because it reduces the value of savings and income, and can be hard to stop. One of the tenets of monetary policy (using interest rates to stop prices rising too much) is a freedom from political pressure on central banks to act in the long-term interests of the country.

Mr Chalmers put pressure on Ms Bullock’s predecessor, Philip Lowe, to lower interest rates, according to Financial Review journalist John Kehoe, by accusing him in a private meeting of ignoring the pain caused by interest rates on regular people.

Neither man would confirm the conversation. In July, 2023, Dr Chalmers effectively fired Dr Lowe by not granting him the second term he wanted. The decision looked to be an example of the government’s treatment of its economic critics.

Critics intimidated

Economists who went public with warnings about the government’s policies received critical messages from Dr Chalmers, sometimes within tens of minutes. Although they did not contain threats, the messages may have been intimidating for anyone hoping for a government position, such as a much-prized seat on the Reserve Bank board.

In Parliament, Dr Chalmers took to ridiculing his Liberal counterpart, Angus Taylor, whenever Mr Taylor cited evidence of the struggling economy.

Mr Taylor argued that, despite low unemployment, most Australians were getting poorer as rising prices ate away at their sluggish wages. The decline was masked by immigration which boosted the official economic figures.

“He has overseen the biggest collapse in Australian living standards in our history,” Mr Taylor says.

Although the causes of lower living standards are multifaceted, the evidence supports Mr Taylor’s claim based on statistics dating to 1959, when comparable records started, according to independent economist Saul Eslake.

Mr Eslake calculates the average Australian’s disposable income fell 10 per cent from September, 2021, to December, 2024. There was probably a bigger drop during the 1930s Great Depression, he said, but the figures aren’t known.

Asked if he has confidence in the powerful public servant who heads the Treasury, Steven Kennedy, given Mr Taylor’s criticism of the government’s economic performance, Mr Taylor did not answer.

Six years lost

Two weeks ago there seemed to be a breakthrough. Economic statistics showed the economy had grown for the first time in two years when adjusted for the size of the population. Celebrating, Mr Albanese said the government was overseeing “responsible economic management with two budget surpluses.”

But some economists said the average Australian was not any wealthier than six years ago, because higher wages had been offset by higher interest rates, prices and taxation, which rose with with inflation.

The difficult economic conditions have left Australians depressed about the future. Satisfaction with life has dropped to its lowest level since since the pandemic and one third of people say they struggle to cover their day-to-day expenses, according to a recent survey conducted by Professor Nicholas Biddle at the Australian National University.

There are no signs the government will offer personal income tax cuts in next week’s budget. With a surplus unlikely until possibly 2035, they would be difficult to justify.

Those deficits will be fuelled by big, long-term spending programs.

In less than three months, the government has promised to spend $36 billion on Medicare, a Queensland highway, the national broadband network and a train line to Sydney’s second international airport. In previous years Labor has offered huge subsidies for wind and solar power, childcare, housing and students.

Some of that spending, such as a plan to build or buy 13,742 subsidised homes, won’t appear in the Federal Budget. That’s because of an accounting rule that allows spending on projects which will theoretically deliver profits to be excluded from the budget.

The off-balance sheet tactic was used by previous governments, Labor and Coalition, but “the Albanese Government has taken it to another new level,” according to Mr Eslake.

Eventually, as their debt gets bigger and bigger, Australians will face tough the decision about how to pay for bigger government.

Special treatment

Back in April, 2022, in one of his last speeches before winning the election, Dr Chalmers foreshadowed a Labor government would give money to businesses it considered worthy of special treatment. The money wouldn’t be squandered, he said, because Labor would be careful economic managers.

“Each of our investments are designed for a generational dividend, and not just a six-to-seven week pay off,” he told the National Press Club in April, 2022.

Last year that promise was fulfilled when parliament passed the $23 billion Future Made in Australia plan.

One of the government’s signature policies, it typified Mr Albanese’s economic philosophy: a belief politicians and public servants can sometimes do a better job at identifying successful business prospects than private investors.

Under the scheme, Industry Minister Ed Husic offered grants through what was called the Industry Growth Program. The scheme promises “to help innovative startups and high-growth small and medium businesses to commercialise their big ideas”.

The grants did not go to profit-making businesses. Instead, $11 million was given to six trade organisation which advise members how to access government services. In other words, the grants were used to encourage more grant applications.

Among the recipients was the Food & Agribusiness Network, which held the party at the Moreton Bay Macadamia Floral Farm on Thursday.

The organisation’s chief executive, Nicole McNaughton, said the function was not paid for by the government, but it does cover the cost of meetings between farmers and produce buyers, investors and advisers. The government also pays for a monthly YouTube video with advice about the food industry, including a recent one on labelling.

“There’s a lot that’s going on in the background,” she said.