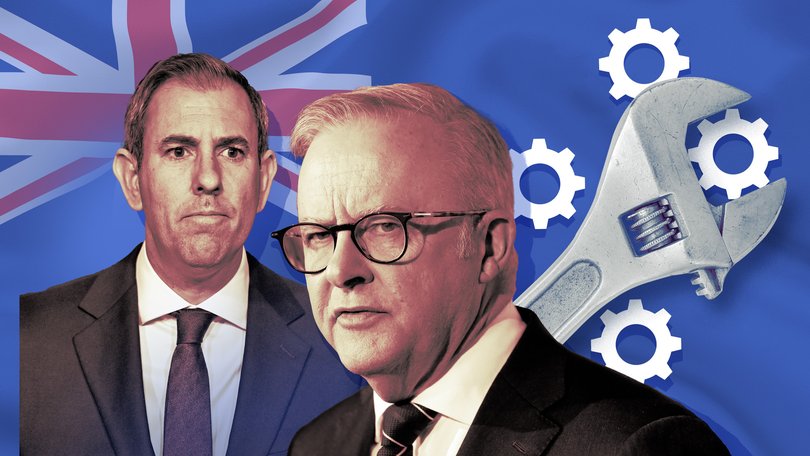

JACKSON HEWETT: Back to the drawing board for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at productivity roundtable

JACKSON HEWETT: Anthony Albanese has announced a new roundtable to pull Australia out of its productivity quagmire — but businesses could be forgiven for feeling a little gun shy.

Businesses are warning that they don’t want to be mugged a second time as the Prime Minister announces a new roundtable to pull Australia out of its productivity quagmire.

At his address to the National Press Club today, Mr Albanese announced he had appointed Jim Chalmers to convene a round table to “shape and support” the Government’s economic reforms.

“We want to build the broadest possible base of support for further economic reform. To drive growth. Boost productivity. Strengthen the budget. And secure the resilience of our economy, in a time of global uncertainty,” he said.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“What we want is a focused dialogue and constructive debate that leads to concrete and tangible actions.”

But business can be forgiven for feeling a little gun shy after rolling up to Labor Jobs and Skills summit in 2022, which prioritised union concerns over those of employers.

“There is some residual scepticism in the business community following the original jobs and skills summit,” Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive Andrew McKellar said.

“But we’ve got to put this aside and approach this with a renewed sense of optimism because there’s almost no greater priority then addressing Australia’s productivity challenges.”

The country’s dire productivity levels are becoming a millstone holding back economic growth. They are a concern to the business sector, which is grappling with higher unit labour costs against an inability to raise prices. And they are also a key issue of increasing concern to the Reserve Bank.

“Am I worried as an Australian citizen, that productivity is not growing? Yes,” RBA governor Michele Bullock said following last month’s interest rate decision, as she warned that the Bank would have to clamp down on the economy in the event wage gains without a lift in productivity caused inflation to rise.

Australian Industry Group chief executive Innes Willox said it was lamentable how little focus productivity received during the election. warning that the country could not afford to let the issue “slide sideways for another five years”.

“Current policy settings at both national and state levels are clearly not working. This summit is therefore ideally timed and needs to focus on immediate reforms that can promptly turn our productivity performance around,” Mr Willox said.

What happened to Australia’s productivity?

Following a boom period in the wake of the Hawke-Keating economic reforms, productivity in Australia has been in a marked decline, and is languishing at its lowest level in 60 years.

There was a brief exception during COVID, when industries with fundamentally low levels of productivity - think accommodation, hospitality and arts and recreation shut down - and workers were reallocated to more productive industries.

Since COVID, however the picture has flipped.

As the economy came out of lockdown and the economy took off, all that available labour dried up as unemployment fell to record lows.

Huge swathes of the workforce were absorbed in government-sponsored work such as infrastructure projects and care economy to the extent that 4 in 5 jobs were government supported. Jobs in health, aged and child care are notoriously hard to measure in terms of output.

At the same time, the small businesses that received taxation concessions to remain solvent ended up limping along rather than going under as would usually happen in a competitive, dynamic economy.

So, instead of productive companies attracting the best and the brightest, they were now forced to take on less and less experienced workers, or pick up workers from overseas who may not have the right set of skills. Worker non-compete clauses also prevent top employees leaving for higher growth outfits.

While workers were spread unproductively across the economy, businesses also pulled back on investment, holding off on buying in new technology to improve worker output. That investment still hasn’t recovered, with machinery and equipment spending down 3.7 per cent over the past year, according to the latest GDP figures.

A recent report into the home-building sector by the Productivity Commission highlights another problem. The report found that Australian builders are finishing half as many homes per hour as they were 30 years ago due to a combination of burdensome red tape across State and local government agencies, a lack of innovation and a sector that is overly reliant on 1-3 person small businesses who are too busy on the tools to develop scale-able processes.

It is also worth noting that part of the historic decline in labour productivity can be sheeted home to the mining industry. The massive investment in the 1990s sent productivity soaring as prices of iron ore and coal soared. As resources prices decline and the mining sector hits a steady state, aggregate productivity levels go with it.

Australia’s lamentable productivity since 2014 is costing $11,000 per person per year, according to economic think tank e61.

Interestingly, Australia’s productivity decline is not unique, with both the UK and the EU releasing landmark reports recently to also try to address the problem.

Each jurisdiction is comparing themselves to the US, which has experienced massive productivity growth. But much of that has come from the transformative impact of its tech firms such as Google and Meta where hundreds of billions are generated by an historically low workforce. Low wage migrants are filling their care economy jobs, whereas countries like Australia have a much fairer, and therefore more attractive, minimum wage.

America also let businesses fail during COVID, using government funds to prop up workers rather than employers, which resulted in a more productive reallocation of labour as the economy rebounded.

What would a summit do

The first thing business wants to avoid is a repeat of the Jobs and Skills summit of 2022. At that event, they say, the ACTU turned up in cahoots with Labor with a raft of proposals that meant a less flexible workforce.

The ACTU also wanted to amend the RBA’s mandate to prioritise employment rather than inflation. Given the dearth of current workers, that would mean lower productivity.

A raft of other progressive initiatives had the AFR’s Phil Coorey describing the summit as a ‘two-day version of The Drum’, the ABC’s now-cancelled evening issues program.

Business leaders said they would have their “eyes wide open” this time, and are prepared to walk away if they feel their voices aren’t being heard.

Australia’s peak business groups, the BCA and ACCI, are calling for urgent reforms to lift productivity and investment. They propose cutting the company tax rate to 25 per cent, boosting business investment through higher asset write-offs, and reducing red tape via faster project approvals and clearer rules for small business.

Both advocate for more flexible workplace laws, streamlined industrial relations, and targeted infrastructure investment to ease housing and energy constraints.

Focusing on reining in government deficits is also on the agenda, as business laments the crowding out of investment.

These are all fine ideas, and are the same sorts of proposals put forward in the UK and Europe - but to little effect.

Perhaps AI, the great hope of business, might be the great hope of governments. Last December, Britain’s Sir Keir Starmer was calling on his regulators to come up with productivity-enhancing ideas. By January he was suggesting AI would ‘turbocharge’ growth to the tune of 47 billion pounds per year.