THE NEW YORK TIMES: Concerns are growing that China’s robotics industry is moving too fast

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Robots have danced on television, staged boxing matches and run marathons. However, concerns are growing that China’s robotics industry is moving too fast.

Robots made by Chinese startups have danced on television, staged boxing matches and run marathons.

When one company debuted its most recent robot last month, people online in China thought it looked so much like a human that workers cut the robot’s leg open onstage to reveal its metal pistons.

Despite the public fascination, concerns are growing that China’s robotics industry is moving too fast.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The robots can mimic human movement and even complete basic tasks. But they are not skilled enough to handle many tasks now done by people. And with so many companies rushing into the industry, Beijing is warning of a bubble.

More than 150 manufacturers are vying for a piece of the market, the Chinese government said last month, warning that the industry was at risk for a crowd of “highly repetitive products.”

“China has an attack-first approach when it comes to the adoption of new technology,” said Lian Jye Su, a chief analyst at Omdia, a tech research firm.

But this generally leads to a large number of vendors fighting for small chunks of market.

As it did with electric vehicles, China has gained an early global lead in making robots. China is using more robots in factories than the rest of the world combined, moving farther ahead of Japan, the United States, South Korea and Germany.

Robots have transformed Chinese factory lines, doing such things as welding car parts and lifting boxes onto conveyor belts.

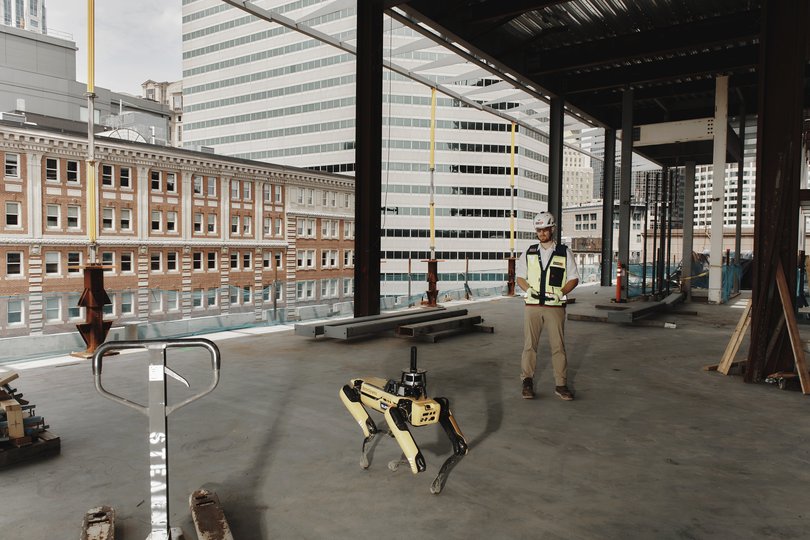

It’s not unusual to run into a robot in Beijing. Robotic machines deliver room service in hotels and buff the floors in airports. Four-legged robots help deliver packages on university campuses. Robots cooked and served food in canteens during the 2022 Winter Olympics.

But China is also working on the next frontier of robotics: robots that not only look but think and act like people.

Public and private investors spent more than $5 billion this year on startups making humanoid robots — the same amount spent in the past five years combined.

Chinese robot makers have significant advantages. They are able to draw on the world’s strongest manufacturing sector and the backing of multiple levels of government. They are getting better at making parts such as the motors and specialised screws in robot joints.

What Chinese robot startups have not been able to do is make humanoid robots that could transform the economy.

Experts say the humanoid robots that have been released struggle with unpredictable situations. They can be programmed to follow patterns, but they have a hard time reacting to events as they happen.

Chinese companies are realising that making robots is not enough, said PK Tseng, a research manager at TrendForce, a market research firm in Taipei, Taiwan. “Without use cases, even if they can ship the products, they don’t know where to sell them,” he said.

Company founders and investors believe that artificial intelligence will be the answer and that humanoid robots could be how AI becomes a physical force in the world.

In Silicon Valley, tech executives often talk about achieving what they call artificial general intelligence. There is no settled definition, but for many it is the idea that AI could match the powers of the human mind.

In China, robotics companies claim they will make AGI a reality.

“For people in China, AGI should be something that benefits people in their everyday life,” said Sunny Cheung, a fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, which studies Chinese government influence. “Robotics is a testament of applied AI in real life.”

But there is a big gap between this vision and the current abilities of robots. Many Chinese robotics startups are working on software they hope will transform robot behaviour the way large language models have transformed AI.

One way that robots can learn to act more like people is by repetitively doing basic tasks. For example, a limited number of robots made by UBTech Robotics, which is based in Shenzhen like dozens of other startups, have been lifting boxes over and over again at electric vehicle factories.

Another way to train robots is by simulation, in which they watch a lot of videos of the thing they will do. Many of China’s leading robotics startups use software and chips made by the Silicon Valley company Nvidia to run their robots’ simulation training, Mr Cheung said.

While no one is certain how useful humanoid robots will turn out to be, China has already put 2 million manufacturing robots to use. Factories in China installed nearly 300,000 new robots last year, while U.S. factories installed 34,000.

Chinese factories have also gotten better at making robots, a major advantage over foreign firms that struggle to manufacture them in large numbers.

The startup Unitree Robotics has announced plans to do an initial public offering, which could provide the capital it needs to help it become China’s leading humanoid robotics maker.

Its latest basic humanoid robots are priced at about $6,000 in China, a fraction of the price of robots made by Boston Dynamics, long the leading American player in the industry. Boston Dynamics was acquired by the South Korean giant Hyundai Motor Co. in 2020.

Major AI research labs, universities and startups in the United States have bought Unitree robots in recent months to test the robots’ abilities and interactions with their software.

Chinese robot makers can offer lower prices in part because they are getting a lot of funding from municipal governments and state-backed hedge funds.

The Beijing government has started a $14 billion fund to invest in AI and robotics. Shanghai set up an embodied AI fund with an initial investment of about $77 million.

In Hangzhou, a tech hot spot, Unitree and a rival, Deep Robotics, are part of a group of AI and robotics startups that the Chinese media has crowned the “six dragons.” The AI startup DeepSeek is another.

This month, Deep Robotics said it had raised $70 million in its latest funding round.

The humanoid robot maker Robotera said in November that it had raised more than $140 million from investors, including the venture capital arm of Geely, an electric carmaker, and the Beijing city government’s dedicated investment funds for robotics and artificial intelligence.

In late November, the Chinese central government set up a committee to establish industry standards. Members included founders, university research labs, municipal government hedge funds and Chinese state officials working on cryptography.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times