Bali bomb conspirators broken by torture, face intense surveillance in Malaysia, Guantanamo lawyer says

Two Malaysians convicted for their role in the Bali bombings and repatriated last week will face intense monitoring, says Guantanamo lawyer.

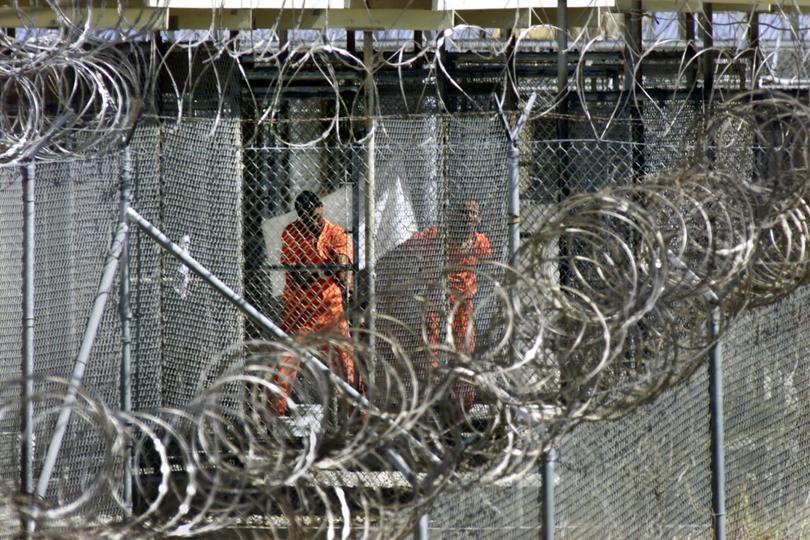

Two Malaysians convicted for their role in the Bali bombings are broken men who no longer pose a danger to society after their repatriation from Guantanamo Bay, according to a senior defence attorney working at the notorious US military prison.

Detainees held in Guantanamo’s extreme conditions and subjected to torture like Mohammed Farik bin Amin and Mohammed Nazir bin Lep, now suffered “debilitating” psychological conditions, said Alka Pradhan, an attorney with the Military Commissions Defense Organisation (MCDO).

In addition, they faced intense monitoring on release, she said, amid a backlash in Australia over the homecoming of the two men who were found guilty of conspiring in the 2002 terror atrocity that killed more than 200 people, including 88 Australians.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“The surveillance on the men is unrelenting. No matter where they are released, it is constant,” Ms Pradhan said in an exclusive interview with The Nightly. “No one disappears after they get out of Guantanamo.”

The Australian government last week urged Malaysia to give assurances that the two prisoners would be closely watched when they returned from the high security military prison in Cuba after more than 20 years in US custody.

The men, who acted as money couriers to support the attack masterminds, were held for 18 years in Guantanamo before being sentenced in January by a military jury to 23 further years after they pleaded guilty to conspiring in the bombings and murder in violation of the law of war.

Their sentences were reduced to five years after they agreed to give evidence against the alleged ringleader, Encep Nurjaman, known as Hambali, and the Malaysian authorities have stressed they will undergo “comprehensive rehabilitation.”

All three suspects were arrested in 2003 in Thailand and taken to CIA black sites or clandestine prisons run by the US administration where they were tortured, according to a 2014 US Senate committee investigation.

At his January trial, Mr Farik bin Amin’s defence team cited federal and congressional evidence he was held naked in isolation while shackled in painful positions and forced to squat with a broom behind his knees, reported The New York Times.

Drawings by Mr Nazir bin Lep depicted torture including being spread-eagled on a tarpaulin while subjected to a crude form of waterboarding.

In 2006, all three men were moved to Guantanamo Bay, which once housed 780 men of which only 27 remain. They were held as “forever prisoners” without trial for the next 17 years, much of this period in solitary confinement.

Human rights attorney Ms Pradhan has worked at Guantanamo for over a decade for the MCDO, a team that provides independent client-based defence services under the Military Commission Act to ensure the Rule of Law and public confidence that the US is pursuing equal justice.

She did not directly deal with the case of the two Malaysians but has represented detainees accused of facilitating the 9/11 attacks and has rare behind-the-scenes insights into the harsh conditions of Guantanamo Bay.

Men who had been held in CIA black sites were transferred to Guantanamo’s “Camp 7”, where they were detained in solitary confinement for over a decade and sensory deprived with blindfolds and blacked out vans any time they left the site, said Ms Pradhan.

They had been restrained for hours and days at a time with wrist and ankle shackles in torturous practices rivalling the worst of US Supermax prisons that were also under United Nations scrutiny.

All the men from the now closed Camp 7 were “suffering from extreme PTSD, extreme anxiety, all sorts of psychological disorders that are really debilitating,” said Ms Pradhan.

“Having worked with a number of them, these are not the sort of men who you spend years with and say they’re dangerous anymore,” she added.

“The first thing that strikes you is how damaged they are. Many of them can’t sit under bright lights anymore. They can’t look you in the eye. They have nervous tics. They need constant care.

“The hope really is, in transferring them, that they will have access to the sort of psychological and medical care that they have not had at Guantanamo.”

Ms Pradhan said her work with 9/11 defendants had revealed they were “extraordinarily ill,” leaving her confident they were of no danger to society.

The release of the Malaysians has been deeply upsetting for survivors of the Bali bombings and loved ones of the victims.

Jan Laczynski, a Melbourne man who lost five friends in the attack, said the repatriation last week had caused “devastation” to a lot of family members.

“It’s Christmas time and we’re greeted with this news..this terrible news, that these two Malaysians, they’re getting a fresh start,” he told the ABC.

Ms Pradhan said each case had to be handled sensitively to ensure victims families did not unduly feel that they were not getting justice.

“The US would have been very careful about how they were speaking to the victim family members, how, in what detail, what they were being informed of,” she said, adding that feedback would have been incorporated into negotiations with the Malaysian government.

A judge with full visibility of the case would have taken into account the impact on the victims as well as the fate of the two defendants.

“Everyone’s familiar with what the treatment was like at the black sites. They were really brutally tortured, and there’s no getting around that fact,” said Ms Pradhan.

“Two things can be true at once. The first is that a horrific crime took place, and there are victims of that crime,” she said.

“Also, that these men after they were picked up were treated in a way that violates our laws.”

The emotion of the victims and their family members was “entirely understandable” while at the same time, the men had been held in “extraordinarily harsh circumstances” that did not exist in most prisons around the world and had cooperated with the US government.

“Under criminal procedures in the US, in Australia, in most democratic countries, the time they have served is commensurate with what they have pled guilty to,” she said.

Convictions tainted by torture have stained United States’ international reputation for years.

State department and National Security Council officials reported that US allies and foes raised the injustices of Guantanamo, said Ms Pradhan.

Torture accusations had left allies during operations in Afghanistan and Iraq wary of releasing terror suspects into US hands.

“This has not just had an impact on the US’ reputation in democracy and accountability but has actively affected operations on the ground,” she said.