How to talk to your friends and family who are deep into conspiracies

‘They’re lying to us.’ An expert reveals how to get through to someone you believe has fallen down an internet rabbit hole of misinformation.

“I have done my research”. “It’s not a conspiracy”. “They’re lying to us”. “It’s all about control”.

In an age of echo chambers, it seems society is more fragmented than ever before, especially after COVID.

It can feel difficult to talk to people about something they have a set view on, especially when their algorithm feeds them compelling videos that may seem convincing, but are often inaccurate.

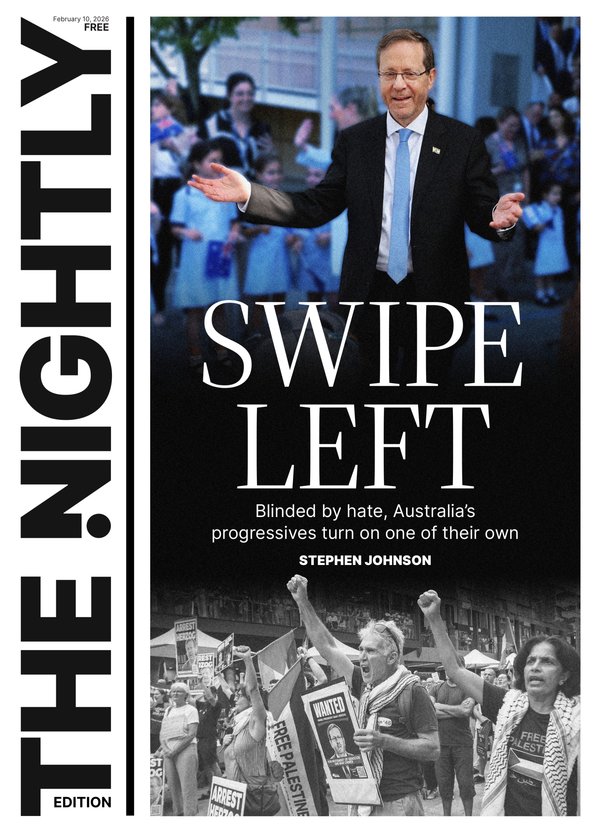

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.So how do you talk to your friends and family if they have fallen down a rabbit hole — and if you think it’s affecting them how can you change the algorithm so that it champions more credible sources?

When someone you care about starts sharing conspiracy theories, the first instinct may be to correct them. But that approach rarely works, says Jessamy Perriam, senior lecturer in the School of Cybernetics at the Australian National University.

“I think one of the challenges is actually knowing what’s verified and what’s credible to begin with,” Ms Perriam says. “There are lots of people who want their content to appear credible, so they either present or write video, audio or text content in a way that looks professional and feels credible.”

As generative AI becomes more widespread, it’s getting harder to tell legitimate information from manipulation.

“It’s about checking the sources and understanding who is saying something and why they might be motivated to say a particular thing,” she says.

Ms Periam says it’s important to use trusted sites like news organisations when searching for information.

“Verified accounts are a good starting place for that and then you know there are other secondary sources that aren’t social media but actual media outlets that have fact checking services or a fact checking section as part of it.”

How to know if information is credible

Determining whether an article can be trusted has changed over the years.

Readers used to be able to tell quite easily if information didn’t make sense or if there were typos, but now it’s much more complicated.

Misinformation can be difficult to spot according to Piers Howe, Associate Professor in the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

“The problem is that nowadays misinformation articles can be so professional looking that it’s really hard to use these deep reading techniques to spot unreliable information, which is why now the advice has changed and it’s natural reading,” he said.

“Natural reading” means that when you spot something that may not be true, don’t continue reading but instead “stop reading the article and start reading naturally,” by finding it on Google, finding out who the source is and what people think about the source.

“It may look like a reputable source but a quick Google could find out it’s a faux.”

Professor Howe said researching could help put facts into context and combat reading information out of context.

According to him, Google itself also tends to prefer more reliable sources, placing them at the top of a search.

“Sure some of these facts might actually be true but they might be taken completely out of context, so natural reading and lots of Googling and not taking things at face value and seeing if multiple reputable sources are saying the same sorts of things, that’s how you determine if something is true.”

How to talk to your friends about misinformation

When it comes to talking to people who’ve been drawn into misinformation, both experts that spoke to The Nightly urged empathy and perspective.

“A lot of people are seeking out help or advice from a really genuine standpoint because they want to be healthy or they want to be living the healthiest life possible” Ms Perriam says.

“Or they might have a legitimate fear of the medical profession based on past experiences. People stumble onto this content as a result of having a genuine information need that they feel isn’t being met elsewhere.”

That’s where shared values can play a crucial role. “When you begin to understand it from that frame of mind it really changes the way that you have conversations with your friends,” she says.

“It becomes a little less combative because in these situations where people are really grasping onto a certain piece of misinformation, actually telling them that they’re wrong may or may not help… They might just dig their heels in a bit more.”

Instead, Ms Perriam recommends grounding these conversations in care. “You personally don’t hold their views,” she says, “but you can reiterate your care for them doesn’t change.”

The goal, she adds, should be maintaining the friendship and leaving space for that person to reconsider their views one day.

“It’s thinking about the relationship you want to have with them in the future, should their views change or become a bit more moderate,” she says. “Are you opening up a safe space for them to continue that friendship with you should they change their mind about what they’re consuming in the media?”

When a friend’s beliefs start veering into more dangerous territory, Ms Perriam suggests honesty delivered gently. “I really appreciate these aspects about you,” she says as an example. “I find these beliefs that you have a little bit worrying and concerning in terms of where things might head next.”

Ms Perriam believes most people are quite good at figuring out if something might be untrue or exaggerated: “they may not be absolutely certain but they’re not that credulous which means if they’re falling for misinformation there is probably some other reason for that.”

The key is not to trigger a defensive response, Mr Howe says.

“They might also go to quite elaborate lengths to try and support the statements which can’t really be supported,” he says.

“And so challenging them is just going to put you down that rabbit hole of fighting all this false information and it’s just gonna set up an antagonistic dynamic, which means you’ll be less effective.

“Try to find out the central reason and trying to empathise with the underlying reason why you might want to believe in false information.

“But then steering them in and away, which is more factual correct, more balanced, and perhaps more productive.”

How to coach your algorithm

Algorithms compound the problem, Ms Perriam explains. “Changing your own algorithm is probably easier than changing someone else’s,” she says.

In terms of YouTube algorithms she used a food example: “If you’re looking up a particular subject area like how to make a particular recipe like fettuccine carbonara and YouTube will be like ‘oh, you’re really interested in fettuccine. Let’s serve you every possible video about that’.”

“It’s more about changing your viewing habits and gently coaching the algorithm away from that kind of content and actually flagging or disliking content that you don’t want to be served up with in the future, and it’ll slowly get the clue that. You’re not vibin’ with that particular piece of content.”

Ultimately, she says the issue of navigating conversations with friends you’re worried about, comes down to perspective and shared humanity rather than debate. “It’s just that thing about thinking about the things you value about your friend but also your fears for them,” she says.

“It’s not necessarily about being right or wrong. It’s about how do you relate to important people in your life when they’re consuming this kind of information.”

Why do people challenge climate change?

“Climate change is pretty well established,” Professor Howe says, “but there are some people who are trying to claim it’s not man-made and that humans aren’t significantly contributing to it, despite that being a very well established fact.

“Trying to just challenge that straight out isn’t going to achieve anything. I mean, that’s been challenged by so many people that it’s not gonna be you who persuades them otherwise.”

Professor Howe said to try and find out the underlying reason behind the person’s concern and tackle the belief that way.

“Often (climate change deniers) live in rural areas and they’re concerned that if we have to take climate change seriously, what it might do for the rural community and what impact it might have,” he said.

“And although they want to be good for the planet they also have other competing concerns, they have loyalty to the community. Their communities may be struggling, they’re really concerned to support the neighbours and that sort of thing.”

Do ‘chemtrails’ make you sick?

The “chemtrails” conspiracy theory, popular on social media and internet forums, claims that the white trails seen behind planes are not ordinary water vapour but deliberate releases of harmful chemicals, supposedly for population control or weather modification.

Despite scientific evidence debunking these claims, the theory persists in various circles, especially where distrust of government and authority runs high.

“Chemtrails, that’s a case of there’s a little bit of truth which is then vastly exaggerated to the point of falsity,” Professor Howe says.

“Chemtrails are those vapour trails you see behind aircraft. You can see a vapour trail, they are man-made, and there was a little bit of pollution in them but they are basically water vapour so they’re basically harmless and a little bit of pollution, that’s just what planes normally emit.

“To fly into Australian airspace, planes have to abide by our emission standards, and so no, they aren’t spewing out a whole lot of toxic chemicals. They will be putting out a little bit just like your car puts out a little bit but just like your car is regulated, so planes are regulated.

“But there is that little element of truth in that these trails that you look up in the sky are indeed man-made, they’re made by planes.

“And the question is this: Why are people saying that? Why are they spreading the conspiracy theories? There’s a lot of reasons. Some people are just lonely and want attention. Other people are concerned about government overreach.

“Often these chemtrails are meant to be some sort of government plot or they’re feeling that capitalism is getting out of control, and the elite, often Bill Gates, or someone like that, is out to control them. So ‘chemtrails’ are just more evidence that they can use to bolster onto this underlying argument that’s out to be controlled.”

He said on the other hand, there is a rational argument for increased regulation of capitalism.

“The fact that Elon Musk is potentially to become a trillionaire and yet a vast amount of Americans are actually concerned about putting food on their table (is an issue),” he said.

Why trustworthy news is important

Misinformation and sensational headlines spread quickly, therefore the role of news organisations in providing credible, responsible information has never been more critical.

Mr Howe explains that questions of credibility have evolved, and today’s media faces a new challenge beyond simply verifying facts.

“So this is part of a bigger question, what is credible?” Mr Howe asked.

“Initially when these questions started to be asked, truthful information was fine. But now we’ve got the concept of malinformation, which is truthful information that is presented in such a way to give a false impression, perhaps by being taken out of context.

“There was a famous case during COVID-19 of a doctor who got the vaccine, had a reaction and died.”

Although the information was true, Mr Howe said it was shared so widely that it created a “distorted perception” of risks associated with the vaccine.

He said many Americans were influenced by this, and decided not to get the vaccine.

Some of them actually died because of this.

“Stories like this can kill people. The United States had more people die unnecessarily due to refusing the COVID-19 vaccine than US combat fatalities in quite a few wars.”

“Between 30 May 2021 and 3 September 2022 there were at least 232,000 deaths in the US caused by COVID-19 vaccine refusal.

“To put that number into some perspective — that’s more deaths than the number of US military fatalities in World War I, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf War and in the War on Terror combined.”

Instagram, Facebook and Tik Tok

When asked about people getting their information solely from Instagram and TikTok, Mr Howe’s reply is frank: “God help us.”

“No, but seriously, that’s why they really have to do natural reading,” he says.

“Sometimes the sources are reliable, sometimes people share mainstream articles on Facebook but often they don’t.

“If you read an article on social media, the first thing you must do is natural reading, so find out what the article says and verify the facts.”