THE ECONOMIST: AI is not the only threat menacing big tech

The biggest worry in Silicon Valley is that the AI boom turns out to be a bubble, but another risk looms.

The biggest worry in Silicon Valley is that the artificial-intelligence boom turns out to be a bubble.

Yet beneath the surface, another risk looms. Digital advertising, which accounts for a large and growing share of big tech’s revenues, is looking less recession-proof. Having shrugged off the previous two downturns of their short history, in 2008-10 and 2020, digital ads are likely to take a serious knock when the next one eventually hits.

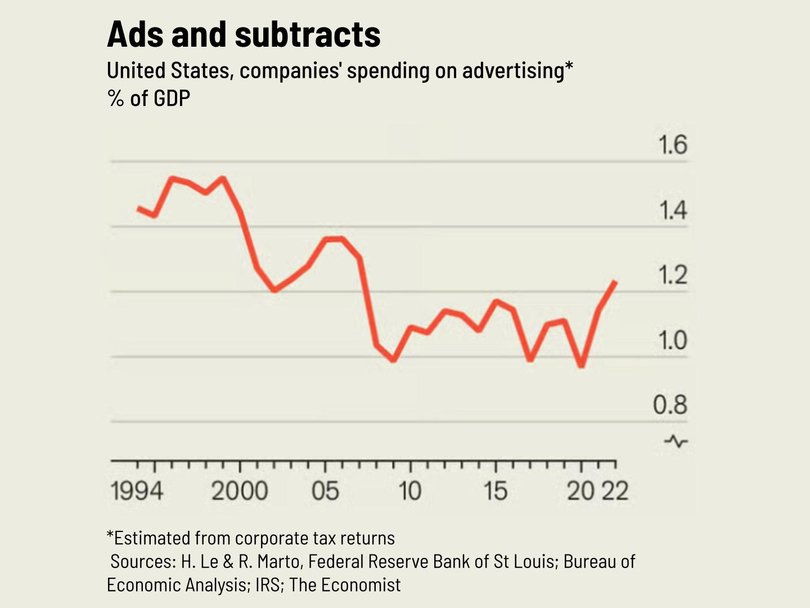

In a typical year American businesses spend 1 to 2 per cent of GDP on advertising (see chart 1, below). Big tech has come to dominate this market, as well as markets abroad, having sucked advertising dollars from newspapers, TV and radio. Digital channels now account for around 60 per cent of worldwide ad spending (excluding China), up from around 30 per cent in 2017.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

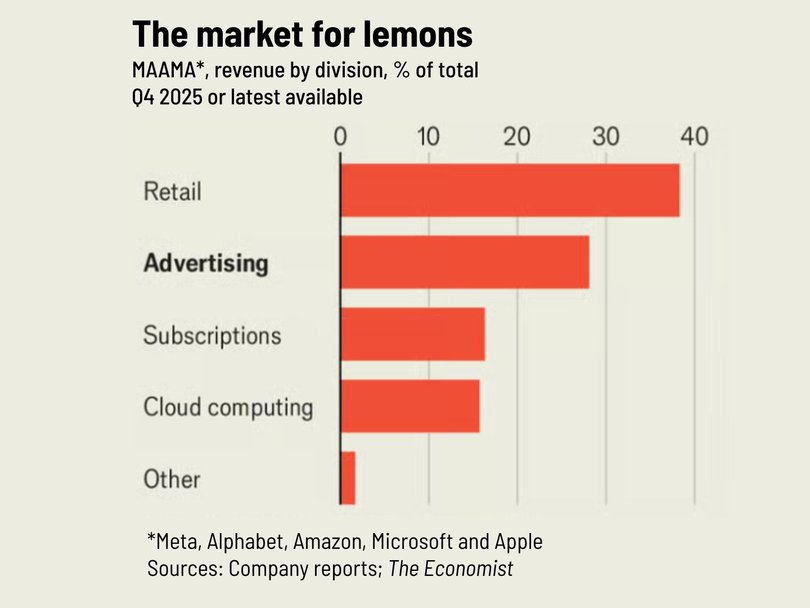

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.America’s tech titans have about an 80 per cent market share of this $US700 billion ($1 trillion) pie, which is likely to grow by a further 10 per cent or so this year.

Ads account for virtually all of Meta’s earnings ($US200b last year), most of Alphabet’s (expected to have hit $US400b) and a growing slice of Amazon’s (analysts reckon it sold nearly $US70b-worth of ads in 2025, nearly double the figure three years earlier).

Even Microsoft and Apple have multibillion-dollar ad sidelines. About 30 per cent of the quintet’s combined sales and profits come from selling ads. (see Chart 2)

In the pre-digital age, this was a cyclical business. Ad spending boomed when the economy was strong and crashed when it was weak.

A paper published in 2008 by Barbara Deleersnyder of Tilburg University and colleagues examined the advertising market in many countries. It suggested that cycles in advertising spending were about 40 per cent more extreme than in the economy as a whole. In 2012 Robert Hall of Stanford University found that during a downturn firms cut ad spending faster than their sales drop.

The cyclicality made sense. Advertising was discretionary, not essential. Its benefits were uncertain. In downturns, executives preferred to preserve cash over building future demand. Cost-cutting was also contagious. Once a few big companies slashed marketing budgets, rivals often followed, lest they appear reckless to their boards and investors.

Big-tech bosses think that digital advertising is different.

Last year Mark Zuckerberg, the boss of Meta, described his company as “well positioned” to navigate macroeconomic uncertainty. In the second quarter of 2025, at a time when the trade war had raised expectations of a recession, Google’s advertising revenues nonetheless rose by 10 per cent year on year.

Many investors in big tech argue that its advertising offering could even benefit from a recession as businesses large and small desperately try to drum up custom.

The economics of digital advertising are certainly unique. In the old days ad-buyers paid up and hoped their customers glanced at the newspaper spread or stayed on the couch during a commercial break.

These days you might only pay when someone actually clicks on a link. Once you would have no idea of your ad’s impact. Now businesses can track their customers’ spending choices in real time.

With AI, targeting and tracking will become even more efficient. And the cost of creating ads could decline to nearly nothing. If businesses come to see digital advertising as a cost of doing business rather than fuzzier brand-building, pressure to cut during downturns may diminish.

Yet there are reasons to doubt the digital ad men’s upbeat pitch. One is history. Pundits have a long record of claiming that a new form of media had made advertising dollars recession-proof, only to be disproved by a subsequent downturn.

In the 1950s, as local TV channels proliferated across America, trade commentary argued that advertisers would adjust campaigns market by market, thus weathering economic downturns without cutting advertising outright.

In 2000 Sumner Redstone, a media mogul, insisted that advertising was “no longer cyclical”, pointing to the strong performance of MTV, a music-video station, during the prior recession.

Neither prediction was borne out. The spread of local TV did not stop businesses from buying fewer ads after the deep slump in 1973-75. More reliable data show that Redstone was wrong, too. American ad spending declined by 28 per cent between 2007 and the early 2010s (after adjusting for inflation).

The recessions of 2008-10 and 2020 are also an imperfect sample from which to extrapolate the future of digital ads. It is true that in both those cases online advertising held up even as offline varieties fell off a cliff.

Yet in 2007-09 digital ads were climbing from a tiny base, so migration of advertising from print and television to the internet offset cyclical weakness.

Now that digital advertising is so dominant, there is less offline share to snaffle. And in 2020 lockdowns forced people temporarily to spend a lot more time looking at screens.

Already digital advertising is displaying some of the old patterns. In a paper from 2020 Jung Kim of the Commonwealth University of Pennsylvania, Bloomsburg, found tentative evidence that online spending is more pro-cyclical than offline spending.

Research published the same year by Alvin Silk of Harvard University and Ernst Berndt of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that in recent years aggregate advertising spending in America “has become more sensitive to the overall performance of the national economy”.

Last year Goldman Sachs, a bank, estimated that since 2020 the correlation between American GDP growth and digital-ad spending has increased.

One reason could be that digital advertisers are highly reliant on custom from small firms, which may be quickest to cut budgets when they perceive that times are bad. Another relates to how firms buy ad space.

Digital ads typically grant more contractual flexibility than non-digital ones, making it easy for businesses to back out.

The next time the macroeconomy is rocked, in other words, the digital ad men may find themselves ordering a particularly stiff martini.

Originally published as AI is not the only threat menacing big tech