THE ECONOMIST: Future of the ex-factory job as blue collar work moves on from manufacturing

THE ECONOMIST: As the Trump Administration strives to fill America’s ‘half empty factories’, manufacturing industries have moved on, while blue collar work has changed.

Trumpian types are unanimous: America needs factories.

The president describes how workers have “watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream”.

Peter Navarro, his trade advisor, says that tariffs will “fill up all of the half-empty factories”.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Howard Lutnick, the commerce secretary, offers the most cartoonish pitch of all: “The army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little screws to make iPhones — that kind of thing is going to come to America.”

For years, politicians and some economists have linked manufacturing’s long decline to stagnant wages, hollowed-out towns and even the opioid crisis. In the 2000s alone America shed nearly 6 million factory jobs.

Such work often offered high-school leavers a route to a stable, quietly prosperous life.

It sustained entire cities, earning Pittsburgh the moniker “Steel City” and Akron that of “Rubber Capital of the World”.

Little surprise, then, that politicians across the spectrum want the jobs back. Indeed, former President Joe Biden shared the same dream as his successor, even if he hoped to achieve it by different means. “Where the hell is it written”, he asked, “that we’re not going to be the manufacturing capital of the world again?”

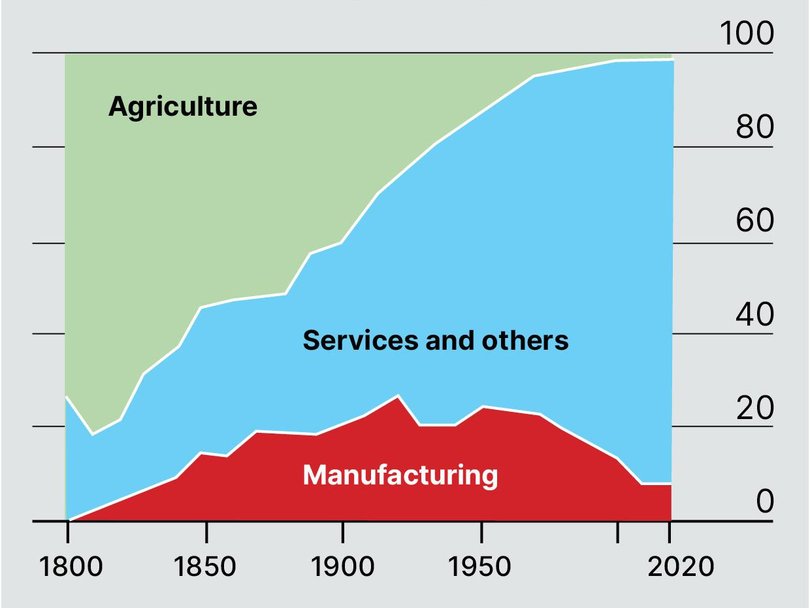

Yet there is a problem: even if industry returns, the old jobs will not. Manufacturing produces more than in the past with fewer hands — a transformation much like that undergone by agriculture.

Accessible, middle-class work of the sort that once drew crowds to the factory gates in America’s Fordist heyday has all but vanished.

According to our analysis, the most similar work to the manufacturing jobs of the 1970s is not to be found in factories, which are now automated and capital-intensive, but in employment as an electrician, mechanic or police officer. All offer decent wages to those lacking a degree.

Whereas almost a quarter of American workers were employed in manufacturing in the 1970s, today less than one in ten is.

Moreover, half of “manufacturing” jobs are in support roles such as human relations and marketing, or professional ones such as design and engineering.

Fewer than 4 per cent of American workers actually toil on a factory floor. America is not unique. Even Germany, Japan and South Korea, which run large trade surpluses in manufactured goods, have seen steady falls in the share of such employment.

China shed nearly 20m factory jobs from 2013 to 2020 — more than the entire American manufacturing workforce. Research from the IMF calls this trend “the natural outcome of successful economic development”.

As countries grow richer, automation raises output per worker, consumption shifts from goods to services, and labour-intensive production moves abroad.

As the Cato Institute, a think-tank, points out, America’s factories would, on their own, rank as the world’s eighth-largest economy.

Even a heroic reshoring effort eliminating America’s $US1.2 trillion ($1.84t) goods-trade deficit would do little for jobs. In the production of that amount of goods, about $US630b of value-added would come from manufacturing (with the rest attributable to raw materials, transport and so on).

Robert Lawrence of Harvard University estimates that, with each manufacturing worker generating around $US230,000 in value added, bringing back enough production to close the deficit would create around 3m jobs, half on the factory floor. That would lift the share of the workforce in manufacturing production by barely a percentage point.

Assume this was achieved by levying an average effective tariff rate of 20 per cent on America’s $US3t of imports, and it could push up prices by around $US600b, or $US200,000 per manufacturing job “saved”.

It is a high price for jobs that are not as attractive as in the past. Seven decades ago, factories offered a rare bundle: good pay, job security, union protection, plentiful employment and no degree requirement.

By the 1980s, manufacturing workers still earned 10 per cent more than comparable peers in other parts of the economy. Their productivity was also growing faster.

Today factory-floor work lags behind non-supervisory roles in services on hourly pay. There has also been a collapse in the manufacturing wage premium, which compares earnings for similar workers by controlling for age, gender, race and more. Using methods similar to the Department of Commerce and the Economic Policy Institute, we estimate by 2024 the premium had more than halved since the 1980s.

For those without a college education, it has gone entirely, even though such workers still enjoy a premium in the construction and transport industries. Productivity growth has fallen, too: output per industrial worker is now growing more slowly than per service-sector worker, suggesting wage growth will be weak as well.

A crucial component of the “manufacturing jobs are good jobs” argument no longer holds.

And a job in industry is harder to attain, too. Modern factories are high-tech, run by engineers and technicians. In the early 1980s blue-collar assemblers, machine operators and repair workers made up more than half of the manufacturing workforce.

Today they account for less than a third. White-collar professionals outnumber blue-collar factory-floor workers by a wide margin. Even once obtained, a factory job is far less likely to be unionised than in previous decades, with membership having fallen from one in four workers in the 1980s to less than one in ten today.

To find the modern equivalent of such jobs, we looked for employment with the same traits. What offers decent pay, unionisation, requires no degree and can soak up the male workforce? The result: mechanics, repair technicians, security workers and the skilled trades.

Over 7 million Americans work as carpenters, electricians, solar-panel installers and in other such trades; almost all are male and lack a degree.

The median wage is a solid $US25 an hour, unionisation is above average and demand is expected to rise as America upgrades its infrastructure.

Another 5 million toil as repair and maintenance workers — think HVAC technicians and telecom installers — and mechanics, earning wages well above the factory-floor average. Emergency and security workers also show similarities; over a third are union members.

Still, these jobs differ from manufacturing in one way: there is no such thing as an HVAC company town. Factories once powered cities, creating demand for suppliers, logistics and dive bars. The new jobs are more dispersed and, as such, less likely to prop up local economies.

Yet, although the benefits are diffuse, they are almost as large. Nearly as many people are employed in such categories as held manufacturing jobs in the 1990s. With better wages, less credentialism and stronger unions, they look more attractive than modern factory jobs to working-class Americans.

The future is drifting even further from factories. Skilled trades and repair workers should see growth of 5 per cent over the next decade, according to official projections; the number of manufacturing jobs is expected to fall. The fastest-growing categories for workers without degrees are in health-care support and personal care, which are expected to grow by 15 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively.

These include roles such as nursing assistants and child-care workers, and do not look anything like old manufacturing jobs owing to their low pay. The task, as Dani Rodrik of Harvard puts it, is to boost the productivity of the jobs that are actually growing. Perhaps that might include ensuring the adoption of AI, whether for managing medication or diagnosis.

In the late 18th century, Thomas Jefferson viewed farming as the foundation of a self-reliant republic. Influenced by French physiocrats who saw agriculture as the noblest source of national wealth, he believed that working the land was the path to liberty and abundance.

By the 20th century, factory work had inherited that symbolic role. But like farming before it, manufacturing employment fades with rising prosperity and productivity. The heart of working-class America now beats elsewhere.

Originally published as Factory work is overrated. Here are the jobs of the future