THE ECONOMIST: How to invest your huge inheritance. Don’t make mistakes of Gilded Age with generational wealth

What do you stand to inherit? It still feels like a question from a different age, despite its growing importance today. In 2025 people across the rich world will inherit some $US6t, or around 10 per cent of GDP — a figure that has climbed sharply in recent decades.

French bequests have doubled as a share of national output since the 1960s; those in Germany have tripled since the 1970s; Italian inheritances are now worth around 20 per cent of GDP

There are two entirely reasonable responses to this. One is to worry about the new inheritocracy harming society: how it could corrode incentives to work, say, or widen inequality and distort the marriage market.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.The other, if a windfall is coming your way, is to rub your hands in glee and ponder what you ought to do with it.

The typical inheritance is closer to the value of a typical home than to a Vanderbilt-style fortune. Even so, a rising number of people are in line for a bonanza. UBS, a bank, reckons that 53 people became billionaires in 2023 by inheriting money; many more will have received amounts in the hundreds of millions.

Asset prices have climbed so high in recent decades, and inheritance taxes have fallen so low, that the number of very wealthy scions is growing all the time.

Descend from the stratosphere, and a sizeable cohort is set to receive far lower sums that will nevertheless be life-changing. In Britain, for instance, a quarter of 35- to 45-year-olds are expected to inherit more than £280,000 ($586,000).

For these lucky people, the experience of the Vanderbilts and their contemporaries offers a cautionary tale. At the turn of the 20th century, America’s census recorded about 4,000 millionaires, note Victor Haghani and James White, two wealth managers, in their book, “The Missing Billionaires”.

Suppose a quarter of them had at least $US5m (the richest had hundreds) and had invested it in America’s stockmarket. Had they then procreated at the average rate, paid their taxes and spent two per cent of their capital each year, their descendants today would include nearly 16,000 old-money billionaires.

In reality, it is a struggle to find a single one who traces their fortune back to the first Gilded Age.

That is not down to inflation or the 20th century’s wars, but to poor investment and spending decisions. After all, spending 2 per cent of $US5m ($7.68m) in 1900 — that is, $US3.8m in today’s money — would not exactly have consigned anyone to penury. The big question for a 21st-century heir is how to avoid the mistakes of those of the past. In other words, how can you enjoy a nice life while ensuring your inheritance lasts for ever?

Silver spoons for all

Some cheery news is that the question of how to invest, which sounds like the hardest part, need not be solved perfectly. In theory, this would mean finding the blend of risky assets with the best volatility-adjusted return, and comparing it with the “safe” return on inflation-protected government bonds.

You would then solve for an optimal split between the two, which would vary with market conditions.

Thankfully, far simpler procedures can produce spectacular results. Our putative 20th-centurymaires just plonked everything in America’s stockmarket, and did very well. Today, we know they could have done even better without much more effort.

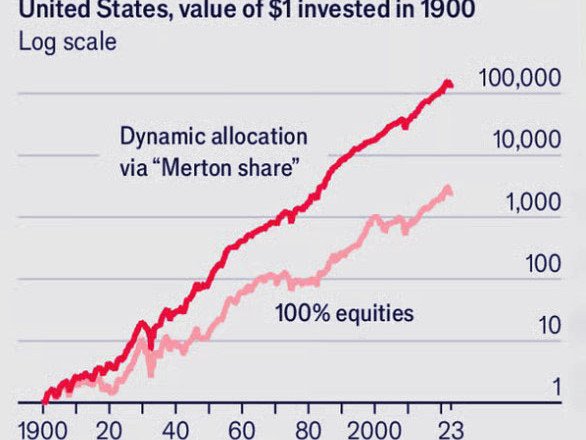

A simple rule-of-thumb known as the “Merton share” can approximate the optimal split between stocks and inflation-protected government bonds, by comparing their expected returns and volatility.

Messrs Haghani and White have calculated the annualised returns on such a strategy since 1900 (using a proxy for inflation-linked bonds for before 1997, when they were first issued).

Had the Gilded Age crowd and their descendants invested in this manner, they would have scored an annualised real return of 10 per cent, compared with 6.6 per cent from the all-stock strategy.

Remarkably, it would also have been 40 per cent less volatile. That would have produced vastly more old-money billionaires today.

The worse news is that deciding how much to spend is trickier than it sounds. Popular rules for drawing down retirement savings, such as spending a largish fixed percentage of the initial value each year, are definitely out. In truth, these are not wise even for pensioners.

Suppose you had kept a classic 60/40 split between American stocks and government bonds, starting in 2000, and drawn down 5 per cent of the value of your initial savings a year.

You would have run out of money in 2019, despite earning an annualised return of 5.25 per cent, since you would have depleted too much capital in the market’s “down” years.

Even if you spent only 4 per cent of the initial value each year — well below the portfolio’s return — you would run a high risk of going bust.

Simulate many different market outcomes, based on the 60/40 portfolio’s expected return and volatility, and the 4 per cent spending rule leads to ruin within three decades about a third of the time.

To avoid this trap, the optimal amount to spend each year must be a percentage of the portfolio’s value at that point (the “spending ratio”), not of its initial value.

In other words, if you want to take the risk required to generate outsize returns, you must vary your (maximum) spending from year to year.

That way, after a bad spell for the markets, you will not deplete too much of the remaining pot, allowing it to recover. Each year you could, for example, spend a proportion of the portfolio’s value equal to its annualised expected return.

This is similar to the spending rule adopted by university endowments, which aim to solve the same problem. The median outcome is that the fund’s value, and hence annual spending, stays roughly constant with time (provided you have not been overly optimistic about your returns).

Nice — but hardly enough to start a dynasty. Ideally, you want to increase your portfolio’s value, which means spending less to let the returns rack up. The trade-offs here are difficult to parse.

You will get pleasure (or, in economists’ jargon, “utility”) from spending more today, albeit with diminishing marginal returns as you get more and more profligate.

Doing so will also trim your descendants’ purchasing power, especially if the portfolio has a large expected return, which you in part forgo by spending now. Yet such returns are inherently uncertain. In any case, it is only human to prefer an immediate pay-off to a delayed one (“time preference”).

The solution is to plug these dynamics into a mathematical model, simulate possible paths for financial markets and calculate the utility derived from each for a given level of spending.

You can then calculate the expected utility for each rule and pick the one that maximises this. Unsurprisingly, the procedure is hard, and generates results that are sensitive to the inputs. Maybe spend some of your money on an excellent financial adviser.

Yet there are straightforward lessons that everyone can absorb. Although greater expected returns allow you to spend more, they do not do so by as much as you might think.

With higher returns, the gap between these and the optimal spending ratio widens (since there is more value in sacrificing spending to let the portfolio grow). Higher volatility means lower spending, since it drags on your annualised return.

The more reluctant you are to vary year-to-year outlays, the less you can tolerate investing in stocks, since their value fluctuates.

The smaller your minimum spending requirement, the more risk you can take, meaning your expected returns, and hence your overall spending, can rise.

A more important lesson is that making your inheritance last for ever means spending far less than its expected return. Exactly how much less depends on market conditions and your risk and time preference.

But under reasonable assumptions, a near-optimal portfolio might have an expected annualised return of 4.1 per cent and an optimal pre-tax spending ratio of 2.4 per cent per year.

Even that is before allowing for how much your family tree might grow, cutting whatever you pass on into smaller chunks.

“People often want to know how much they need to have to give each member of their family’s next few generations a modest income,” says Mr Haghani. “The answer is: a lot more than most anyone thinks.”

Originally published as How to invest your enormous inheritance